By Jay Landers

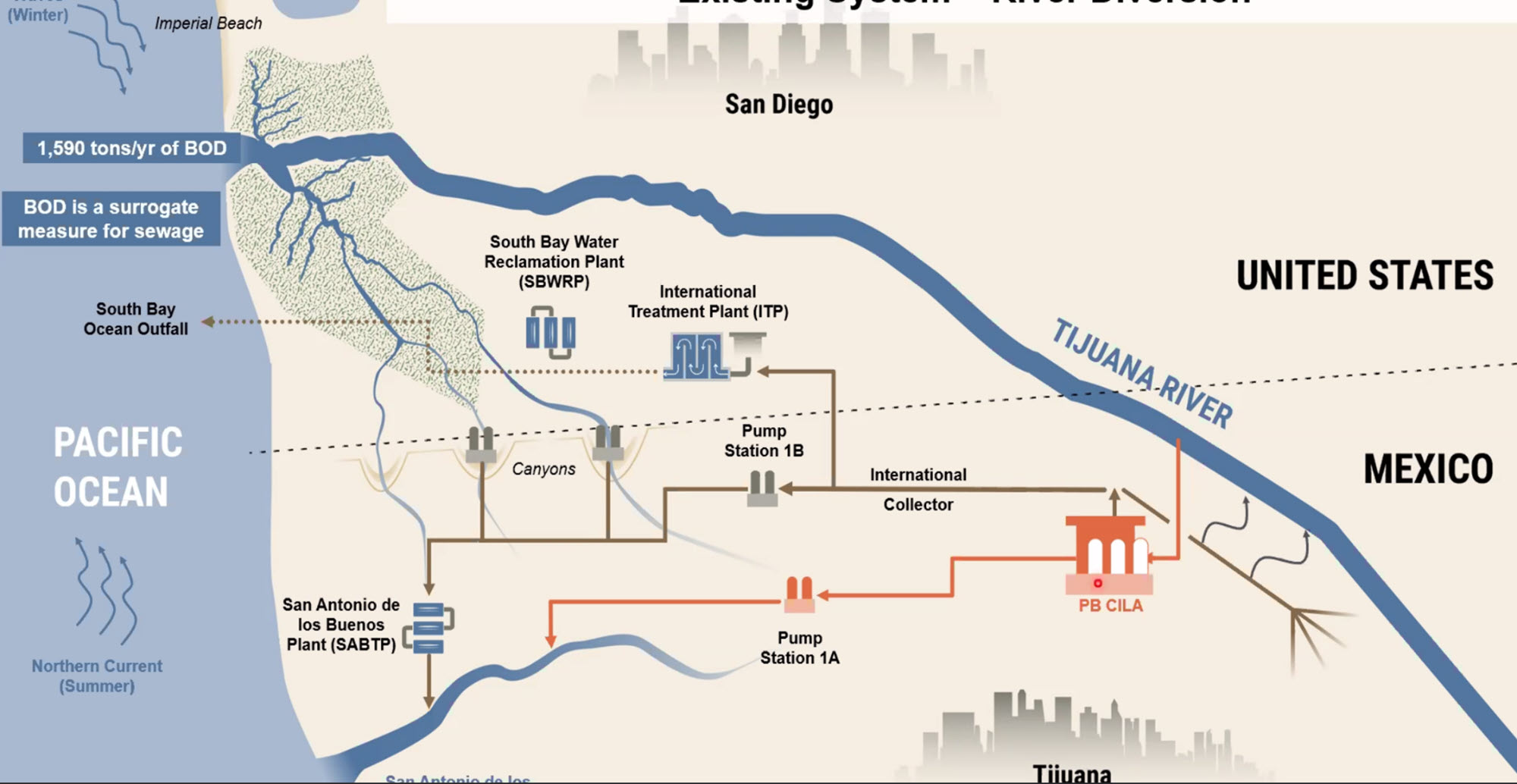

Situated just north of the border of the United States and Mexico, California’s southern San Diego County has long contended with water pollution that originates in nearby Tijuana, Mexico. Much of this water pollution takes the form of raw sewage, industrial chemicals, and stormwater laden with sediment and trash that enter the Tijuana River before crossing the border into the U.S. Additional pollution from the Tijuana region is discharged into the Pacific Ocean several miles south of the border and can be transported northward by ocean currents.

Known as “transboundary flows,” these sources of water pollution have increased significantly in recent years, exacerbating such problems as waterborne illnesses and beach closures in San Diego County and harm to sensitive coastal and marine features. Recently, construction began on a new wastewater treatment plant in Mexico that is expected to help reduce transboundary flows, while the U.S. government is taking steps to repair and upgrade its existing plant that was built to treat wastewater from Tijuana. However, many officials at the local and state levels, frustrated by what they term years of inaction, want to see the scale and pace of planned improvements ramped up to address the burgeoning water pollution problems as soon as possible.

Increasing flows

Approximately three-quarters of the 1,750 sq mi Tijuana River watershed is in Mexico. Originating in that country, the Tijuana River enters the U.S. at San Ysidro, California, and flows several miles before discharging to the Pacific Ocean. Near its mouth, the river passes through the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve, which includes the Tijuana Slough National Wildlife Refuge and Border Field State Park.

Historically, transboundary flows mainly occurred in winter, during the rainy season. During the summer dry season, existing systems for diverting and treating water from the Tijuana River once were able to minimize these flows and their resulting beach closures.

Unfortunately, “rapid urbanization” and “uncontrolled growth” in Tijuana have significantly increased the frequency and volume of transboundary flows, meaning they now occur throughout the year, says Chris Helmer, the environmental and natural resources director for the city of Imperial Beach, California. The southwestern-most city in the continental United States, Imperial Beach is a tourist destination known for its beaches.

Tijuana’s aging network of combined and sanitary sewers has been unable to cope with the city’s growth, Helmer says. “Since 2017, there's been a whole system failure of the sewer system in Tijuana,” he says. “We’ve been just having nonstop inundation of sewage floods.”

The rapid development in Tijuana expanded impermeable surfaces, increasing the volume and velocity of stormwater runoff, says Bryn Evans, a senior project manager for Craftwater Engineering Inc. — a planning, analysis, and engineering firm that focuses on water quality and urban watersheds — and a longtime veteran of projects involving the Tijuana River on both sides of the border.

“What that can do is increase your sediment loading downstream,” Evans says. Besides harming the natural environment, the increased sediment loads obstruct drainage facilities, he notes, including so-called canyon collectors that divert runoff from canyons that convey contaminated stormwater north across the border from Tijuana.

Finally, failing wastewater treatment infrastructure also contributes to the rising volumes of transboundary flows.

‘Wreaking havoc’

The rapid rise in beach closures in recent years reflects the increasingly deleterious effects of transboundary flows in San Diego County. In 2016, the beach at Border Field State Park was closed for 162 days because of water pollution, according to data provided by Helmer.

That same year, two other local beaches — Imperial Beach Pier, in Imperial Beach, and Silver Strand State Beach, in Coronado — were closed 34 and 16 times, respectively. By contrast, the Border Field beach was closed every day in 2023, while Imperial Beach Pier was closed 322 days and Silver Strand 291 days.

“The continuous influx of transboundary pollution is wreaking havoc on the local community, economy, and environment along the coastline of south San Diego County,” said Paloma Aguirre, the mayor of Imperial Beach, in a June 6, 2023, letter to the White House Council on Environmental Quality.

Existing treatment systems

The International Boundary and Water Commission, a binational entity comprising the U.S. and Mexico, oversees efforts to address transboundary flows from Tijuana. As part of such efforts, the U.S. Section of the IBWC constructed the 25 mgd South Bay International WWTP in the late 1990s to treat wastewater from Tijuana and discharge it to the Pacific Ocean by means of the 3.6 mi long South Bay Ocean Outfall. Initially constructed as an advanced primary treatment facility, the South Bay International WWTP was upgraded to include secondary treatment in 2010.

The South Bay facility mainly treats wastewater collected within Tijuana’s sewer system as well as water diverted from the Tijuana River. However, a small proportion of flows to the plant consists of stormwater captured by the canyon collectors.

On the Mexican side of the border, wastewater from Tijuana that is not sent to the South Bay facility is conveyed by a series of pump stations and sewer pipelines to the San Antonio de los Buenos WWTP in Punta Bandera, approximately 6 mi south of the border. Designed to treat up to 25 mgd by means of a lagoon system, the facility discharges to the Pacific Ocean via San Antonio de los Buenos Creek.

However, inadequate maintenance has greatly diminished the treatment capabilities of the San Antonio facility. The treatment plant “in its current condition does not improve the water quality of the effluent,” according to the November 2022 Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement from the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Section of the IBWC, which assessed solutions for addressing contaminated transboundary flows.

Inadequate maintenance

The South Bay treatment facility also has fallen on hard times. Significant increases in flows to the plant have damaged the facility, which already was suffering from inadequate funding for maintenance and repairs.

Between 2010 and 2020, only $4 million was spent to repair and maintain the facility, said Maria-Elena Giner, Ph.D., P.E., the U.S. commissioner of the IBWC, during an Oct. 8, 2023, hearing held by the California Coastal Commission. “Needless to say, that low level of funding did not prioritize this plant as part of the maintenance that was needed,” Giner said. The IBWC has since identified between $100 million and $150 million worth of “urgent rehabilitation needs,” she said.

Since 2020, the South Bay facility has “self-reported more than 350 exceedances of effluent limitations” specified within its Clean Water Act discharge permit, says Frank Fisher, the public affairs chief for the U.S. Section of the IBWC. Compounding the situation, heavy rainfall from Tropical Storm Hilary in August 2023 caused damages to the South Bay facility that will cost an estimated $8 million to repair. Despite these challenges, the IBWC intends for the plant “to achieve permit compliance” by Aug. 15, Fisher says.

Planned improvements

In August 2022, the U.S. and Mexican sections of the IBWC entered into an agreement formally known as Minute No. 328, calling for a combined total of $474 million in infrastructure improvements intended to reduce the volume of untreated wastewater originating in Tijuana. Under this agreement, the U.S. committed to spending $330.3 million, while the Mexican government pledged to spend $143.7 million. Of the U.S. spending, $300 million is dedicated to doubling the treatment capacity of the South Bay facility to 50 mgd.

As for the money pledged by the Mexican government, $33.3 million is to be spent on the design and construction of a new wastewater treatment facility to replace the failed San Antonio de los Buenos WWTP. The 18 mgd replacement facility will use an “oxidation ditch process” comprising three independent modules, according to Minute No. 328. The project also will include the construction of a 656 ft long ocean outfall.

Doubling the capacity of the South Bay facility and replacing the San Antonio de los Buenos WWTP will increase the volume of Mexican wastewater receiving treatment by 43 mgd, according to the Aug. 18, 2022, news release from the EPA announcing the adoption of Minute No. 328. Upon completion, all the projects called for in the agreement are expected to “result in a 50% reduction in the number of days of transboundary wastewater flow in the Tijuana River,” according to the release.

On Jan. 11, Mexican and U.S. officials gathered for a groundbreaking ceremony at the site of the planned replacement facility in Punta Bandera, according to a same-day article in the San Diego Union-Tribune. During the ceremony, Marina del Pilar Avila Olmeda, the governor of the Mexican state of Baja California, pledged that the new WWTP would be operational by the end of September, according to the Union-Tribune.

The remaining $110.4 million to be spent by the Mexican government mainly will rehabilitate outdated or failed wastewater collection infrastructure in Tijuana. The Mexican Section of the IBWC did not respond to inquiries from Civil Engineering Online regarding when these additional improvements would be completed.

In early December 2023, the IBWC solicited proposals from interested parties for the expansion of the South Bay facility from 25 to 50 mgd “with additional capacity to treat daily peak flows up to 75 mgd reliably for temporary periods and still meet permit compliance,” according to a Dec. 8 news release from the commission.

The contract for the project, which will be delivered by means of the progressive design-build approach, is expected to be awarded in early summer, Fisher says. However, the $290 million in federal funding that has been appropriated for the project is far short of what the planned improvements are expected to cost. All told, the project has an estimated cost of approximately $600 million, plus or minus 30%, Fisher says.

In its supplemental budget request submitted to Congress in October 2023, the White House requested an additional $310 million for the South Bay WWTP. On March 23, President Joe Biden signed into law the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 (H.R. 2882), legislation funding multiple federal agencies through the end of the fiscal year. The law included approximately $156 million for the IBWC's construction amount, nearly 400% of the president's FY 2024 budget request for the commission, Fisher says. The construction funding was provided "with the clearly expressed congressional intent a substantial amount of those funds will be spent on the rehabilitation and expansion of" the South Bay facility," Fisher says. The law also boosted funding for operations and maintenance at the South Bay plant and other key IBWC facilities.

In her June letter to the White House Council on Environmental Quality, Aguirre called for a federal emergency declaration “to coordinate and prioritize a multiagency response to this ongoing disaster.”

This article is published by Civil Engineering Online.