Brian Brenner, P.E., F.ASCE, is a professor of the practice at Tufts University and a principal engineer with Tighe & Bond in Westwood, Massachusetts. His collections of essays, Don’t Throw This Away!, Bridginess, and Too Much Information, were published by ASCE Press and are available in the ASCE Library.

In his Civil Engineering Source series More Water Under the Bridge, Brenner shares some thoughts each month about life as a civil engineer, considering bridge engineering from a unique, often comical point of view.

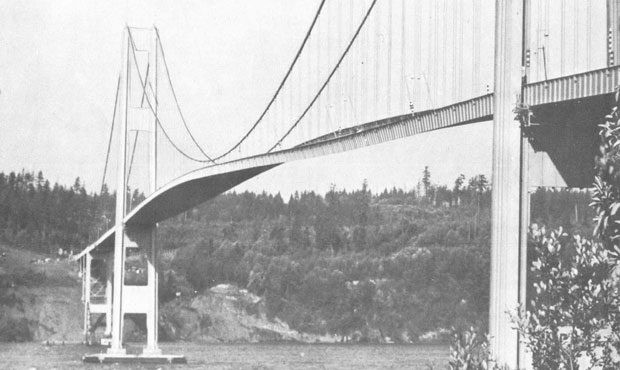

On Thursday, Nov. 7, 1940, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapsed. The bridge crossed a southern inlet of Puget Sound in Washington State. When it opened in July, it was the world’s third-longest bridge span. It lasted about four months.

The collapse is considered to be one of the most significant bridge disasters, in part because of its dramatic failure. It is probably the most photogenic failure, thanks to the many photos and films taken of the collapse. The tragedy has served a supporting role in the education of decades of bridge engineers, and has led to substantial changes in suspension bridge design and understanding of structural behavior under wind loading. Fortunately, there were no human fatalities, but a dog perished when the car he was trapped in plummeted into the Narrows.

Many refer to the doomed dog as “Professor Farquharson’s dog,” but this is inaccurate. Professor F.B. [Frederick Burt] Farquharson was the last person on the bridge, and more about his efforts below. But the dog actually belonged to the daughter of Leonard Coatsworth.

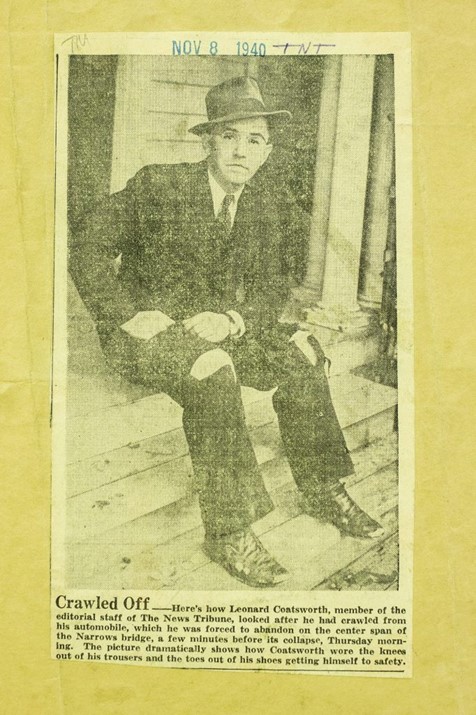

Mr. Coatsworth was an editor at The News Tribune, the daily newspaper of Tacoma, Washington. On Nov. 7, 1940, he was driving back to his daughter’s house with the dog in the back seat. He started to cross the bridge and passed the first tower when the span started to sway violently. His experience is described here.

After the main span collapsed and his car plummeted into the Narrows, Coatsworth remembered: “With real tragedy, disaster and blasted dreams all around me, I believe that right at this minute what appalls me most is that within a few hours I must tell my daughter that her dog is dead, when I might have saved him.”

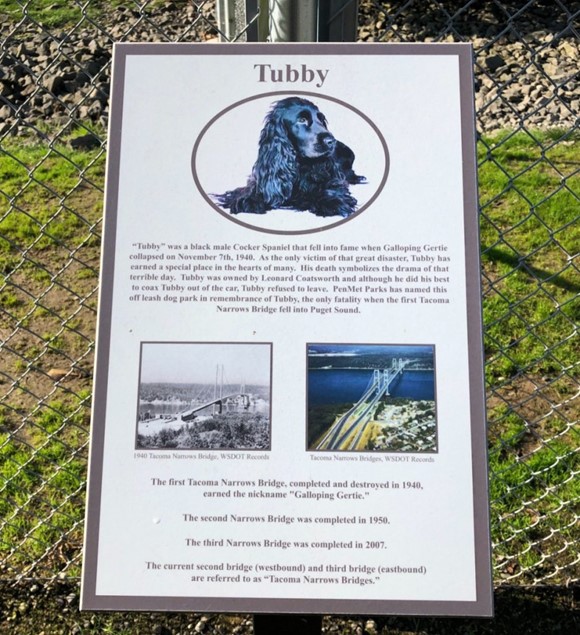

Coatsworth’s daughter’s dog led a difficult life. He was a cocker spaniel named “Tubby.” There is not much documentation available about his life prior to the bridge collapse, and I am not sure if he/she was male or female, but in this article I’ll refer to him as “him.” We do know that Tubby was missing a leg and was partially paralyzed. Here’s more about Tubby:

https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBHistory/tubby-trivia.htm

https://gritcitymag.com/2018/11/searching-for-tubby-the-tacoma-narrows-bridge-collapses-only-victim/

The day of the collapse, Coatsworth drove eastbound across the bridge toward Tacoma. The vertical motion of the main span increased to the point that Coatsworth could no longer drive after making it about halfway onto the main span. He exited the car and was flung to the pavement. He tried to retrieve Tubby, huddled in the back seat. But the dog was terrified and would not leave. Coatsworth ended up crawling on the deck to safety.

Farquharson was the last person on the bridge. Farquharson was a civil engineering professor at the University of Washington. He served as a consultant to help develop ways to stiffen the bridge. He was at the site to study the bridge’s unusual motion, which, before the destructive twist began, was more of a rolling motion. November 7 was not the first day the span swayed. Shortly after its opening, the main span was known to move in the wind and it received the nickname, “Galloping Gertie.” If you weren’t an engineer or professor, this movement was considered to be entertaining, like riding a roller coaster, but not necessarily dangerous. On November 7, a stiff gale set upon Puget Sound, enhancing the span’s rolling movement. The professor had brought along still cameras and a motion picture film recorder as well. Likewise, some local residents had 16mm film cameras. It is interesting that the disaster is so well documented on film, keeping in mind that 1940 predated smartphones by about 70 years. The most well-known film loop of the collapse was taken by Barry Elliott, a Tacoma native. His film was saved and digitized.

After failed attempts by others to rescue Tubby, Farquharson tried. He walked out to the car, balancing himself on the now rotating axis of the main span. Unfortunately, Tubby was not receptive to this last rescue attempt. He bit the professor. The span’s violent motion assumed its final, fatal twisting movement. Farquharson realized he was in danger and walked/crawled back to the east shore. The main span gave way soon after that, sending Coatsworth’s car and his daughter’s dog plummeting into the Narrows. The water was reported to be over 100 feet deep at that location. The car and Tubby’s remains were never found.

The dog is memorialized at a park named “Tubby’s Trail,” in Gig Harbor, Washington. The dog park was developed on the site of a concrete batch plant used for construction of the third Tacoma Narrows Bridge. A plaque at the entrance describes some of the backstory. It shows a generic picture of a cocker spaniel, since there were no clear photos available of Tubby.

Legend has it that after a dog passes, he crosses a “Rainbow Bridge” to a place where there are green hills and meadows. Many other pets play and frolic in the hills. In this legend, the pets are restored to good health and are well fed and happy.

For Tubby, who lived a difficult life and experienced a traumatic passing, arrival at the peaceful hills must have been a moment of particular grace. But it does beg the question (at least for a bridge engineer): What type of bridge did Tubby cross to get there? Keep in mind that in the passage to heaven, Tubby did not have a good experience with bridges while on earth.

There is little information available to address this question of bridge type in the journey to the hereafter, but we can use the engineering method supported by conjecture to speculate.

Let us assume that the distance between the here and now and the hereafter is substantial. This distance would not only be great in plan, but also great in terms of the obstacles to be crossed. Therefore, a long-span bridge would almost certainly be required, not just for the lateral distance, but also because of the likely difficulty of placing piers in the space below in the gap between the here and now and the hereafter.

Considering the geotechnical design, there is no information available about substrata conditions in the hereafter. We can assume that soil in the hereafter is good, with excellent bearing capacity and high blow counts. But on the waiting shore? Probably thick, underconsolidated clay.

Of structural types available for design and construction of the Rainbow Bridge, long-span options include a tied-arch, a cantilever truss, a cable-stayed bridge, and a suspension bridge. Selecting the most appropriate alternative introduces another unusual question not addressed in most bridge-type studies. For this structure, what time frame is appropriate? Should we consider design criteria for the crossing based on today’s technology and standards, or should the timing be based on the year, 1940?

To better understand at least the structural parameters of this issue, we can visit Queensferry, Scotland, just east of Edinburgh. At this location, three beautiful long-span bridges cross the Forth River. The bridges are representative of three different eras of long-span design and construction. The Forth Rail Bridge is an iconic and massive double-span cantilever truss entering service in 1890. In 1964, the Forth Road Bridge opened. It was Europe’s longest-span suspension bridge. Most recently, the Queensferry Bridge was built and opened in 2017, a spectacular double cable-stayed bridge.

The three bridges cross the Forth side by side in a timeless display of bridge-spanning technology. But to address the question of design criteria for the Rainbow Bridge, is this even relevant? The here and now has a linear timeline, but would not the hereafter have no timeline at all? In the hereafter, a bridge could be a more primitive stone clapper bridge, or perhaps a neural network antigravity floating span supported by air jets (this structural type has not been invented yet).

So, in absence of further guidance, let us assume that the Rainbow Bridge crossed by Tubby was a suspension bridge, since cable-stayed bridges were not yet in vogue. But this suspension bridge would have been well-designed and stiffened by a deep deck truss similar to the second Tacoma Narrows Bridge and the later Mackinac Bridge in Michigan. We must believe that if Tubby crossed one last bridge, it was a structure that did not move perceivably in the wind.

Another possibility is that Tubby did not have to cross a bridge at all, but was granted passage through a specially constructed tunnel so as to avoid the difficult experience of crossing a bridge. At this point, Tubby likely suffered from gephyrophobia.

Our conjecture concludes with this thought: Even with the challenges of possibly crossing one last bridge, Tubby made it successfully to the green pastures on the waiting side. He is there, joyfully frolicking on his four healthy legs through eternity. The legend of the Rainbow Bridge includes the idea that at some time, faithful pets and their owners are reunited in the hereafter to frolic together in beautiful meadows on the far bank of the bridge. In accordance with this legend, we can further assume that Leonard Coatsworth also experienced a sunny crossing, on a stout bridge that did not bounce up and down.

References and further reading

“Tacoma Narrows Bridge history – Tubby trivia”

https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/TNBHistory/tubby-trivia.htm, accessed May 25, 2023.

Harbor History Museum, Gig Harbor, Washington, Tacoma Narrows Bridge image collection

https://harborhistorymuseum.org/image-collection, accessed May 25, 2023.

“700 Feet Down” – documentary film about the bridge collapse.

Facebook site: https://www.facebook.com/700FeetDown, accessed May 25, 2023.

“Searching for Tubby: The Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse’s Only Victim,” by Sara Kay, Grit City Magazine

https://gritcitymag.com/2018/11/searching-for-tubby-the-tacoma-narrows-bridge-collapses-only-victim/, assessed May 23, 2023.

“Tubby’s Trail Dog Park” Park site – Gig Harbor, Washington

https://penmetparks.org/parks/tubbys-trail-dog-park/, assessed May 25, 2023.

University Libraries, University of Washington. Exhibit: History of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge

https://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/collections/exhibits/tnb, assessed May 23, 2023.

“Rainbow Bridge”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainbow_Bridge_(pets), assessed May 23, 2023.

“Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse ‘Gallopin Gertie’”

Video Loop https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-zczJXSxnw, assessed May 23, 2023.