Older parts of Tucson don't have drainage channels, storm drains, or detention basins, according to Jacob Prietto, CFM, the chief hydrologist of the Pima County Regional Flood Control District, the organization that implements flood prevention infrastructure in the greater Tucson area.

When the streets were originally built, “the idea was that all that costs too much, and for the few days that it does rain, we'll just design our streets to carry that flow,” Prietto says. But as the city has grown — adding more impervious streets and parking lots to the city’s watershed — that strategy is no longer adequate.

Now, when a storm hits, “the streets can't contain that flow,” Prietto says, and the water inundates private property and homes. “That's the problem we're working with.”

Ronni Kotwica, the president of the Palo Verde Neighborhood Association, described a 2016 flood in her central Tucson neighborhood that damaged 200 homes — one neighbor had water swirling in her living room. Even though Kotwica and her husband had spent $30,000 trying to flood-proof their home, “our basins (and) cisterns were (still) overwhelmed by the water,” she says.

Decentralized stormwater management

Local water managers, flood control engineers, and architects have been grappling with how to manage these nuisance floods for years. Now, they are pioneering what many call a “decentralized” approach to stormwater infrastructure. That is, one that is not about massive drains and tunnels, but myriad small-scale interventions that can mitigate flooding and provide other social benefits as well.

Instead of a stormwater system that diverts stormwater to centralized storage basins and would likely require demolition of central city blocks to create space for their construction, the flood control district is looking at public parks, schools, churches, or any other type of land that is not devoted to residential, commercial, or industrial use, according to Prietto.

The green infrastructure projects the region is working on exist at two scales. At the smallest scale are local interventions that range from curb openings to chicanes, vegetated or rock swales, or pervious pavement. At a larger scale, city and county leaders are designing storage basins in parks and other greenways to create more places to temporarily store water.

For instance, last year, the flood control district completed work on the Seneca Street Basins and Neighborhood Park, which diverts stormwater from the street and into a series of shallow, 1 ft deep basins in the park. The district is planning to create a similar project at another pocket park later this year. These basins are meant to allow captured water to infiltrate into the ground and feed local vegetation — the basins are designed to a shallow depth so water doesn’t stagnate before it can percolate into the ground.

Re-leveling the playing field

Courtney Crosson, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Arizona, runs design studios and conducts research on urban sustainability and puts the challenge this way: “How do you retrofit a city for infrastructure that it doesn't have? The idea is that instead of digging up roads and putting in single-purpose piping, green infrastructure is a multi-benefit way to adapt and upgrade city infrastructure.”

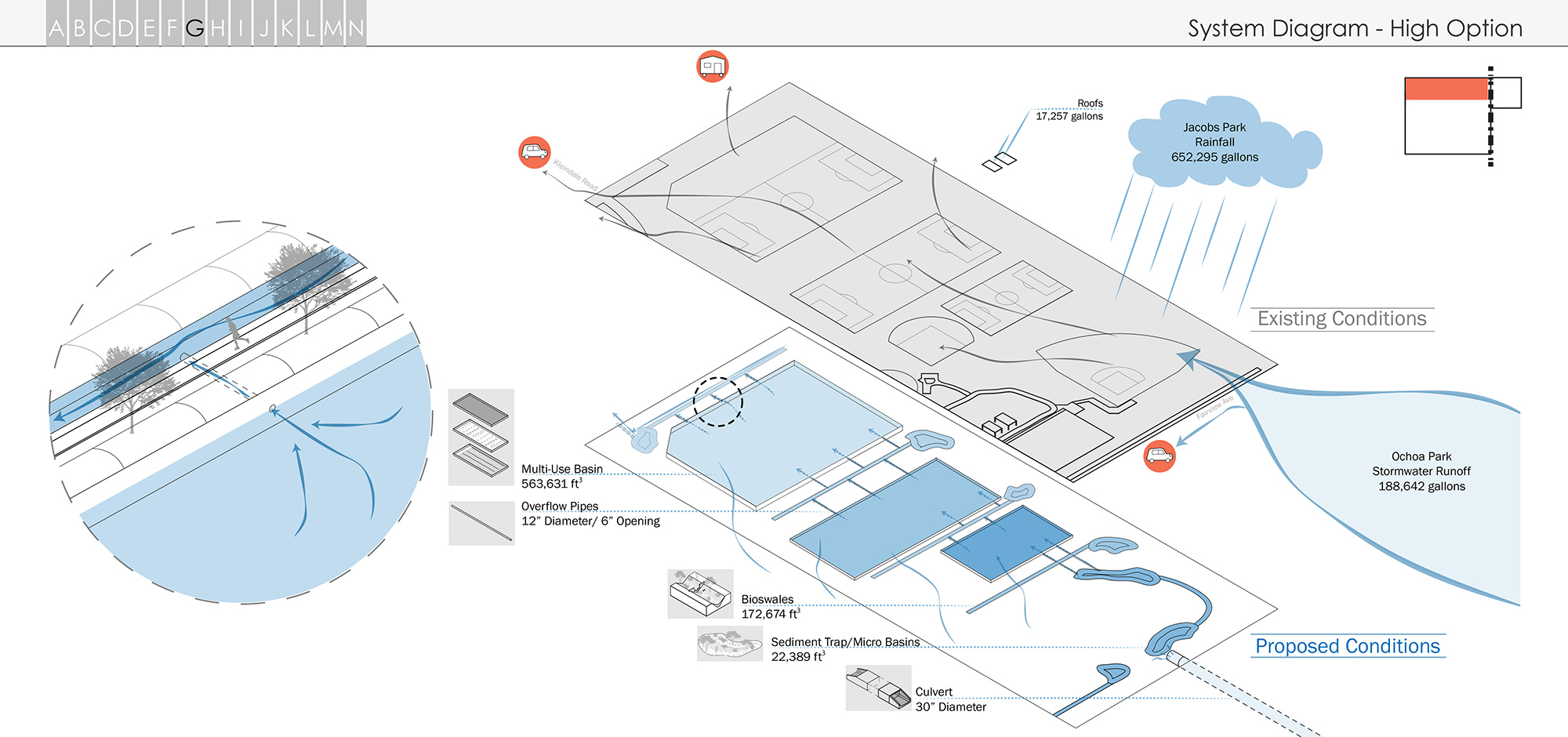

In one of her design studios, Crosson and her students partnered with the flood control district to explore how a large soccer field at Jacobs Park-Nicolas P. Ochoa Soccer Complex on the city’s north side could be redesigned to serve as a temporary detention basin.

“Instead of building a big canal, what if we took our soccer fields and lowered them a foot or two so that right after monsoons, they're acting as detentions for a day or two?” says Crosson. "But then after that, they can be used again. Because we're only getting these isolated storms, this idea of multipurpose green infrastructure makes sense.”

Prietto says this is more than a student exercise; he describes it as a "marketing campaign” to share information about the technical benefits of basins and where they can unobtrusively be located to mitigate flooding. “We need to get clear information to our decision-makers,” he says.

Funding

The city is using a pair of relatively new funding mechanisms to drive its efforts to decentralize stormwater management. In 2018, city voters approved Proposition 407, a $225 million bond package for capital improvements for city parks, recreation centers, pedestrian paths, and bike trails. So far more than 150 park, bike, and pathway projects have been identified. While this money is earmarked specifically for park upgrades, planners and engineers expect that green infrastructure interventions, funded separately, will be built alongside the park improvements.

More recently, the city created a green stormwater infrastructure fund last year. The projects funded through this are designed to irrigate plants with stormwater, reduce stormwater pollution, and shade and cool streets and bikeways. The GSI fund is supported by a monthly fee of 13 cents per centum cubic ft to Tucson Water customers (which averages out to a modest $1.04 yearly charge). The water agency expects to raise about $3 million a year. Of that, $2.3 million will go to capital projects, another $300,000 for maintaining existing chicanes and medians, and the rest for a small staff to oversee the program.

Though it was officially created in February 2020, the fund is only now getting off the ground, having endured delays caused by the pandemic. Its first project will divert stormwater into a city park and plant 30-50 new trees (the same park will receive 150 additional tree plantings through the Proposition 407 funds).

The power of small-scale interventions

There is evidence that these small-scale interventions can help. Evan Canfield, P.E., M.ASCE, the manager for the watershed studies division at the flood control district, notes that a 2009 white paper the district wrote concluded that “the most important scale to implement stormwater harvesting is at the lot and neighborhood scale. The differential between the runoff from the impervious and predevelopment was greatest at the smallest scales.”

A study on converting a so-called gray street to a green street determined a benefit-to-cost ratio of 6-to-1. The benefit wasn’t just mitigating stormwater, he adds, it was planting trees, providing shade in the hottest months, calming traffic, and using more stormwater and less potable water to grow vegetation.

The benefits are widespread, and “we are increasingly partnering with Tucson Water, Tucson Parks, Pima County Parks, and Pima County Community Development to work in green spaces,” Canfield says. Another aim of these projects — and the GSI fund — is to prioritize interventions in lower-income neighborhoods that are more prone to flooding due to their elevation or lack of vegetation or tree canopy.