By Jay Landers

In July, the Pacific Gas & Electric Co. — one of the nation’s largest gas and electric utilities — announced its intention to install underground about 10,000 mi of its above-ground electric distribution power lines that are located in areas at high risk of wildfire.

Potentially costing upward of $20 billion, the multiyear initiative is expected to decrease the extent to which PG&E’s power lines cause wildfires, reduce the investor-owned utility’s maintenance costs, and improve the reliability of electricity distribution in California.

However, PG&E will have to overcome a host of technical and logistical challenges as it seeks to implement its ambitious plans in a cost-effective, efficient manner.

Past devastation

PG&E provides natural gas and electricity to roughly 16 million people throughout a 70,000 sq mi area in central and Northern California. The utility owns and operates nearly 107,000 mi of electric distribution lines and nearly 18,500 mi of interconnected electric transmission lines, according to the company’s website. Of PG&E’s electric distribution lines, more than 25,000 mi of its overhead lines are maintained in the state’s highest fire-threat areas, as defined by the California Public Utilities Commission. (A map of the area and the locations of its three fire hazard tier designations is available here.)

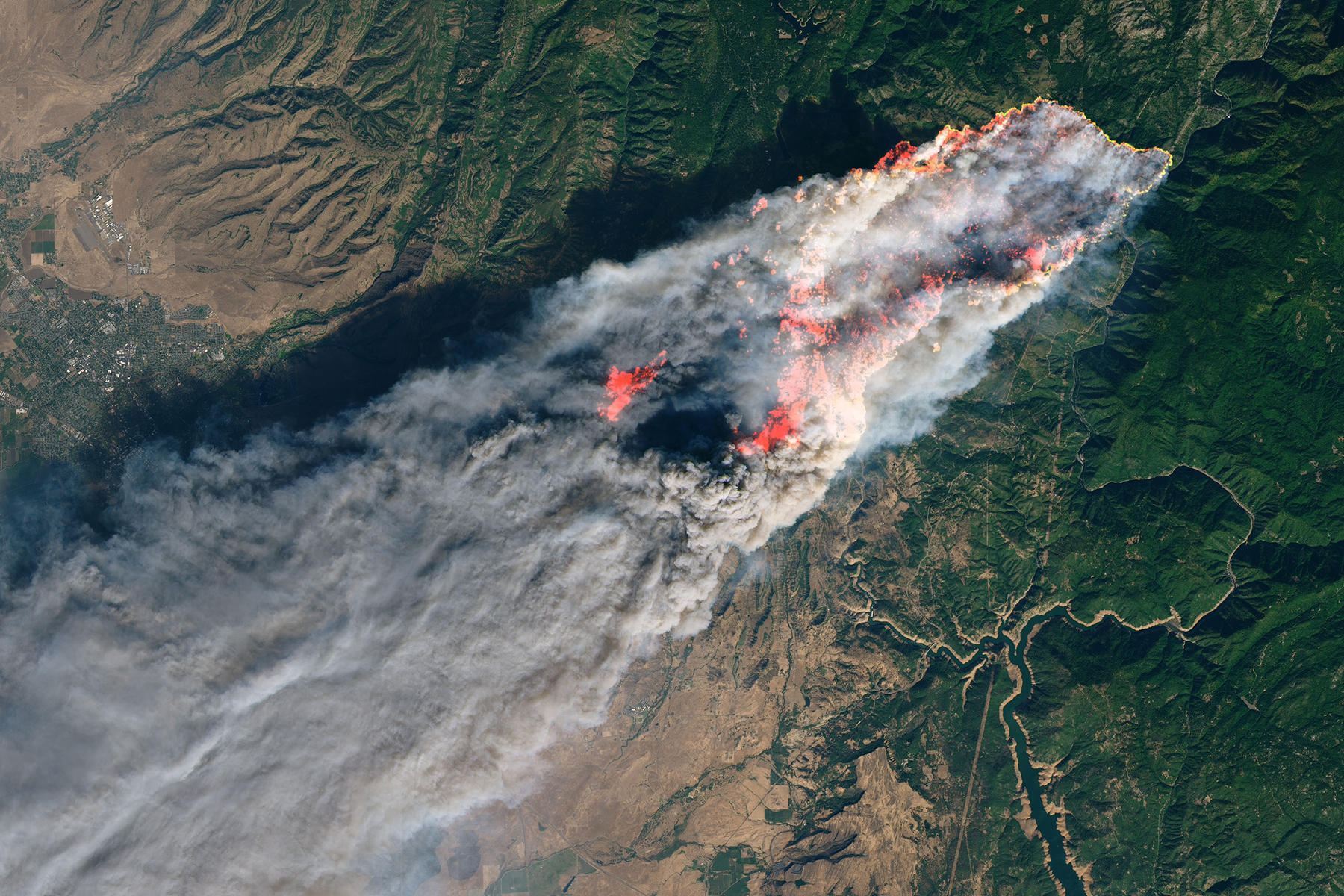

In recent years, PG&E’s above-ground power lines have been blamed for causing multiple California wildfires by coming into contact with vegetation. In May 2019, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection determined that electrical transmission lines owned by PG&E started the Camp Fire in Butte County in November 2018.

The deadliest conflagration in California’s history, the Camp Fire killed 85 people and burned more than 153,000 acres. PG&E subsequently pleaded guilty to 84 charges of manslaughter related to the fire. Liabilities associated with that and other fires prompted the utility to enter bankruptcy in 2019.

“We want what all of our customers want: a safe and resilient energy system,” said Patricia Poppe, the CEO of the PG&E Corp., the parent company of PG&E, in a July 21 news release.

“We have taken a stand that catastrophic wildfires shall stop,” Poppe said. “We will partner with the best and the brightest to bring that stand to life.”

Underground benefits

In addition to reducing the risk of wildfires, undergrounding the lines in the most fire-prone areas will benefit utility customers in other ways, PG&E says. For example, the process will lessen the need for what are known as public safety power shut-offs during dry, windy conditions, according to the utility’s news release. Although shutting off power to customers in this manner helps prevent wildfires that otherwise would occur when vegetation contacts live power lines and creates sparks, such shut-offs decrease the reliability of the distribution system. At the same time, “undergrounding also eases the need for vegetation management efforts, leaving more of California’s trees untouched,” the release states.

Absent undergrounding or conducting significantly more vegetation management, PG&E’s electric distribution lines can be expected to cause more wildfires in the future, says Samuel Ariaratnam, Ph.D., P.E., NAC, F.ASCE, the Beavers-Ames Chair in Heavy Construction and the construction engineering program chair at Arizona State University. With climate change leading to hotter temperatures and drier conditions, “it’s a recipe for fires occurring around those lines,” Ariaratnam says. But once the power lines are underground, “it’s not an issue,” he says.

PG&E potentially could realize other benefits from undergrounding its power lines, Ariaratnam says. For example, underground lines are better protected against damage from inclement weather, including high-wind events and ice storms, he points out. Underground lines are “not exposed to the elements, which is a big thing from a maintenance or a disruption perspective,” Ariaratnam says. “Maintenance costs from inclement weather are very important to look at.”

Steep costs

Although undergrounding power lines offers certain benefits, it will not come cheap.

“We are still in the process of scoping this work, but we estimate the total cost to underground 10,000 mi of overhead power lines to be approximately $15 billion to $20 billion or more,” says Ari Vanrenen, a PG&E spokesperson.

“The cost of converting an overhead distribution power line to underground depends on several variables,” Vanrenen says. Such variables include the terrain, the density of nearby residences and businesses, the surrounding vegetation, the number of power lines involved, the presence of other existing underground structures, and the extent to which road widths in project areas inhibit or facilitate work access, she notes.

PG&E has not set annual targets for undergrounding certain amounts of its electric distribution lines. “The exact number of projects or miles undergrounded each year through PG&E’s new expanded undergrounding program will evolve as PG&E performs further project scoping and inspections, estimating, and engineering review,” according to the release.

Potential challenges

Key challenges to be addressed by PG&E as it proceeds with its undergrounding initiative will involve route planning and technology selection, Ariaratnam says. “Route selection is going to be critical,” he says, particularly given the forested nature of much of the areas in which the utility will be working. Ultimately, PG&E will need to develop a “systematic way” to plan the routes of its new underground power lines, Ariaratnam says.

Next, PG&E will need to determine whether to use open-cut or trenchless construction on a given section of undergrounded power line, Ariaratnam says. “Open-cut and horizontal directional drilling would be the main ways they’re going to look at for undergrounding above-ground lines,” he notes. “Both of them are excellent construction approaches for underground construction.” These decisions typically come down to such factors as the types of terrain, the presence of existing underground utilities, and the availability of access for construction equipment, Ariaratnam says.

Because of labor shortages, PG&E and its contractors might have trouble simply getting the skilled workers needed to conduct the undergrounding projects. “Getting that workforce together to be able to tackle those projects is something that, as an industry, we’re all working on,” Ariaratnam says.

Another challenge that PG&E will need to address is the decreased efficiency of electricity transfer in underground power lines as compared with overhead lines, says Brian Dorwart, P.E., P.G., M.ASCE, a senior consultant for the Brierley Associates Corp. Because they are encased in insulating soil that traps heat, underground lines heat up more than do overhead lines that are surrounded by air. Higher temperatures increase resistance within the underground line, decreasing system efficiency and increasing distribution costs, Dorwart says.

To address this problem, the heat in the soil must be conveyed away from the lines by thermal grouting or other types of heat-conducting materials. These materials must be capable of maintaining proper temperatures within underground lines, so as to enhance the amount of power that can flow through them, Dorwart says.

At the same time, the material surrounding the cable must ensure that the surrounding ground does not heat up to the point that it dries out, because dry ground is less able to transfer heat. When that happens and water is absent in the surrounding ground, “the cable is going to heat up more and more,” he says. “Eventually (the line) will exceed the capacity of the cable insulation, and the current will arc to the ground,” resulting in an explosion and damage to the system, Dorwart says. “You have to have materials surrounding underground cables that can be reliable over the years to be able to keep its integrity for heat dissipation.”

Ramping up

PG&E acknowledges that the rollout of its undergrounding effort may move slowly at first but maintains that it can overcome the challenges in a timely manner.

“There will be an initial ramp-up period due to limitations in our supply chain and labor force,” Vanrenen says. “However, within a couple of years, we will be doing 10 times the mileage we are doing today and more,” she says. “We will get to the point where we are completing well over 1,000 mi per year.”

PG&E’s future efforts to underground its electric distribution lines will build on similar work conducted previously by the utility on a smaller scale. In recent years, PG&E has begun undergrounding power lines as part of efforts to harden its system. To this end, the utility undergrounded 6.8 mi in 2019, 4.6 mi in 2020, and 5.9 mi in 2021, as of July, Vanrenen says.

Although done on a much smaller scale than what PG&E intends to do regarding undergrounding, this experience has helped the utility prepare for its more ambitious plans. “Through current demonstration projects and rebuild efforts, we have been able to refine the costs and construction requirements associated with targeted undergrounding, enabling the acceleration and expansion of undergrounding projects,” Vanrenen says.