By Jay Landers

The Great Lakes — Erie, Huron, Michigan, Ontario, and Superior — form one of the world’s largest surface freshwater ecosystems and have long borne the brunt of past pollution from industrial, urban, and agricultural sources. Decades ago, more than 40 hot spots of extreme pollution, labeled Areas of Concern, were identified by the U.S. and Canadian governments around the Great Lakes region.

Despite commitments from both nations to clean up these AOCs, progress has been slow. However, President Joe Biden’s administration recently committed to spending $1 billion over five years to remediate and restore the AOCs, a move that is expected to greatly accelerate the cleanups of the remaining degraded sites.

Bulk of the $1 billion

Signed into law in November, the massive Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included $1 billion over five years in supplemental funding for the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, a multiagency effort led by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to protect and restore the Great Lakes. The legislation, which is also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, did not specify how this funding was to be spent. But in mid-February, the Biden administration announced that essentially all of it would be directed to addressing AOCs.

The EPA “will use the bulk of the $1 billion investment in the Great Lakes from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to clean up and restore” the remaining AOCs, the agency said in a Feb. 17 news release. “This will allow for a major acceleration of progress that will deliver significant environmental, economic, health, and recreational benefits for communities throughout the Great Lakes region.”

Biden, announcing the plans for the $1 billion at a Feb. 17 event in Lorain, Ohio, went even further: “It’s going to allow the most significant restoration of the Great Lakes in the history of the Great Lakes,” Biden said, according to a transcript from the White House.

Legacy pollution

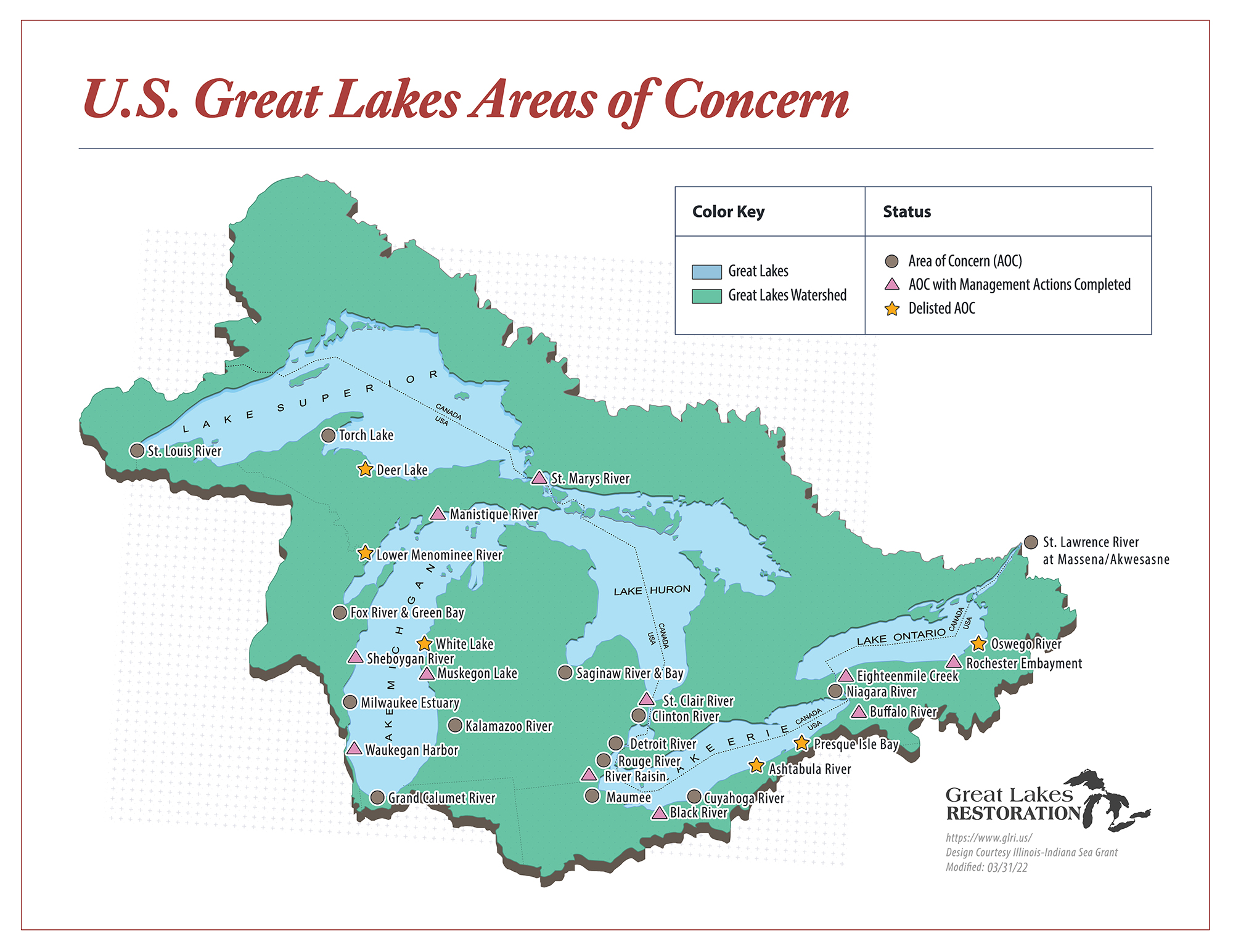

In 1972, the United States and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, formally committing each nation to restore and protect the waters of the Great Lakes. In 1987, the agreement was amended to designate the 43 AOC sites in need of major restoration to address significant environmental degradation. Of the 43 sites, 26 were in the United States, 12 were in Canada, and five were binational locations to be addressed by both countries. (A list of the 26 U.S. AOCs and the five binational AOCs is available online.)

To be listed as an AOC, a site had to have been found to have at least one of the following 14 beneficial-use impairments:

- Restrictions on fish and wildlife consumption.

- Tainting of fish and wildlife flavor.

- Degradation of fish and wildlife populations.

- Fish tumors or other deformities.

- Bird or animal deformities or reproduction problems.

- Degradation of benthos.

- Loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

- Restrictions on dredging activities.

- Eutrophication or undesirable algae.

- Restrictions on drinking water consumption or taste and odor problems.

- Beach closings.

- Degradation of aesthetics.

- Added costs to agriculture or industry.

- Degradation of phytoplankton and zooplankton populations.

“The legacy of decades of industrial pollution still haunts many communities,” says Laura Rubin, director of Healing Our Waters-Great Lakes Coalition, an environmental advocacy group. “Areas of Concern contain high levels of cancer-causing and health-threatening pollution, such as (polychlorinated biphenyls), mercury, and other chemicals, that have poisoned the water and led to drinking water restrictions, fish consumption advisories, and beach closures.”

Although spread throughout all eight of the U.S. states that are located within the watershed of the Great Lakes, AOCs typically are situated “near population centers” and “along the shoreline” of major waterways, says Donald Jodrey, the director of federal relations for the nonprofit advocacy organization the Alliance for the Great Lakes.

Comparing AOCs to “mini-Superfund sites,” Jodrey says that cleaning up the areas will lead to “demonstrable improvement” in the ecological health of urban shorelines currently affected by past pollution.

Slow start

Because of funding limitations, remediation of the AOCs proceeded slowly at first. For an AOC to be considered restored, all its designated beneficial-use impairments must be removed in accordance with restoration targets set by state and local advisory groups. Following the removal of all such impairments, an AOC is delisted, meaning that its cleanup process is complete.

Since the formation of the GLRI in 2010, the U.S. government, acting through multiple federal agencies, has increased funding significantly for addressing AOCs and taking other steps to improve the water bodies.

To date, six of the U.S. AOCs have been delisted and the required management actions have been completed at another 11 of the sites, according to the EPA. Before the latter sites can be delisted, monitoring typically must be conducted to confirm that restoration targets have been met.

Faster cleanups

The new funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, combined with annual funds appropriated through the GLRI and other sources, will enable the EPA and its partners to complete work at 22 of the remaining 25 U.S. and binational AOCs by 2030, the agency said. Of the 22 sites, 11 will benefit directly from the funding afforded by the new infrastructure law. As of 2030, only three AOCs will still require work to complete their remediation.

Exactly which AOCs will receive funding for remediation from the IIJA money has yet to be determined. The EPA is “in the process of identifying specific AOC remediation and restoration projects to receive IIJA funding,” says Chris Korleski, the director of the agency’s Great Lakes National Program Office. “The specific projects are not known at this time.”

The approach or approaches needed to clean up an AOC depends on the types of contamination present at the site. However, the “three top issues” to be addressed at most AOCs are “contaminated sediments assessment and remediation, wastewater treatment plant upgrades, (and) habitat restoration,” says Gail Krantzberg, Ph.D., a professor of the Master of Engineering and Public Policy program in the W Booth School of Engineering Practice and Technology at McMaster University, in Hamilton, Ontario. Krantzberg’s research focuses on the Great Lakes, environmental restoration science, and public policy.

Environmental and economic benefits

Addressing the various problems at the AOCs will result in significant environmental improvements, particularly as it relates to contaminated sediment, Korleski says. “Cleaning up AOCs will include the remediation of millions of pounds of long-contaminated sediments containing toxic chemicals like PCBs, dangerous metals such as mercury and chromium, and other toxic chemicals, which have continued to degrade Great Lakes water quality for — in many places — over a century,” Korleski says.

Ultimately, remediating the AOCs will improve the environment and human health while boosting local economies, Rubin said. “All waters are connected, so cleaning up these especially toxic hot spots is necessary for the health of our communities and for our fish and wildlife — and can be a key driver of local economic revitalization,” Rubin says. “The recent announcement of a $1 billion influx into AOC work will be a game-changer, accelerating the cleanup of these serious threats that have impacted the millions of people of the region.”

The infrastructure law funding could have additional benefits for the Great Lakes, the EPA says, by freeing up resources to address such priorities as addressing harmful algal blooms, nutrient reduction activities, protecting against invasive species, and monitoring the health of the lakes themselves. The agency “anticipates additional resources could be available for these and other priorities because of the infusion of resources from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” according to the EPA’s release.