By Jenny Jones

An internet search of the top engineering breakthroughs of the 21st century reveals impressive results. Groundbreaking innovations like the Sky Crane, the Large Hadron Collider, the Burj Khalifa, 3D printing, and the Mars Opportunity and Curiosity rovers make the list. But, according to a new report from the Society of Women Engineers, one much-desired advancement continues to elude nearly all fields of engineering in the United States: gender parity.

Each year for the past two decades, SWE has examined social science research to understand this underrepresentation of women in engineering. In this year’s report, “Women in Engineering: Analyzing 20 Years of Social Science Literature,” authors Peter Meiksins, Ph.D., professor emeritus of sociology at Cleveland State University, and Peggy Layne, P.E., F.SWE, found that while the percentages of women earning engineering degrees, holding engineering faculty positions, and working as employed engineers have all increased through the years, the growth has been slow. Women earned only 23% of engineering degrees in 2020, held just 18.5% of engineering faculty positions in 2021, and accounted for a mere 14% of engineering employment in 2019.

"We want to make sure researchers are paying attention to the issues regarding not just recruitment but also retention,” said Roberta Rincon, Ph.D., the associate director of research for SWE, in a press conference.

“Right now, we’re hovering around 14% of the engineers in the workplace being women,” Rincon said. “That has increased over the last 20 years from about 11%. It is slowly increasing, but it is far below what we’re seeing among engineering graduates. Why is that? We have to understand the factors that are preventing us from diversifying the engineering profession because if we just continue on this path, it is going to take us a century to reach anywhere close to gender parity.”

Attracting women

According to the report, the percentage of Bachelor of Science degrees in engineering earned by women has increased significantly over the years, from less than 1% in 1954 to 23% in 2020. But much of this gain occurred during the 1970s and 1980s. Since 1990, the report states, the percentage of women earning engineering degrees has been sluggish and has varied by discipline.

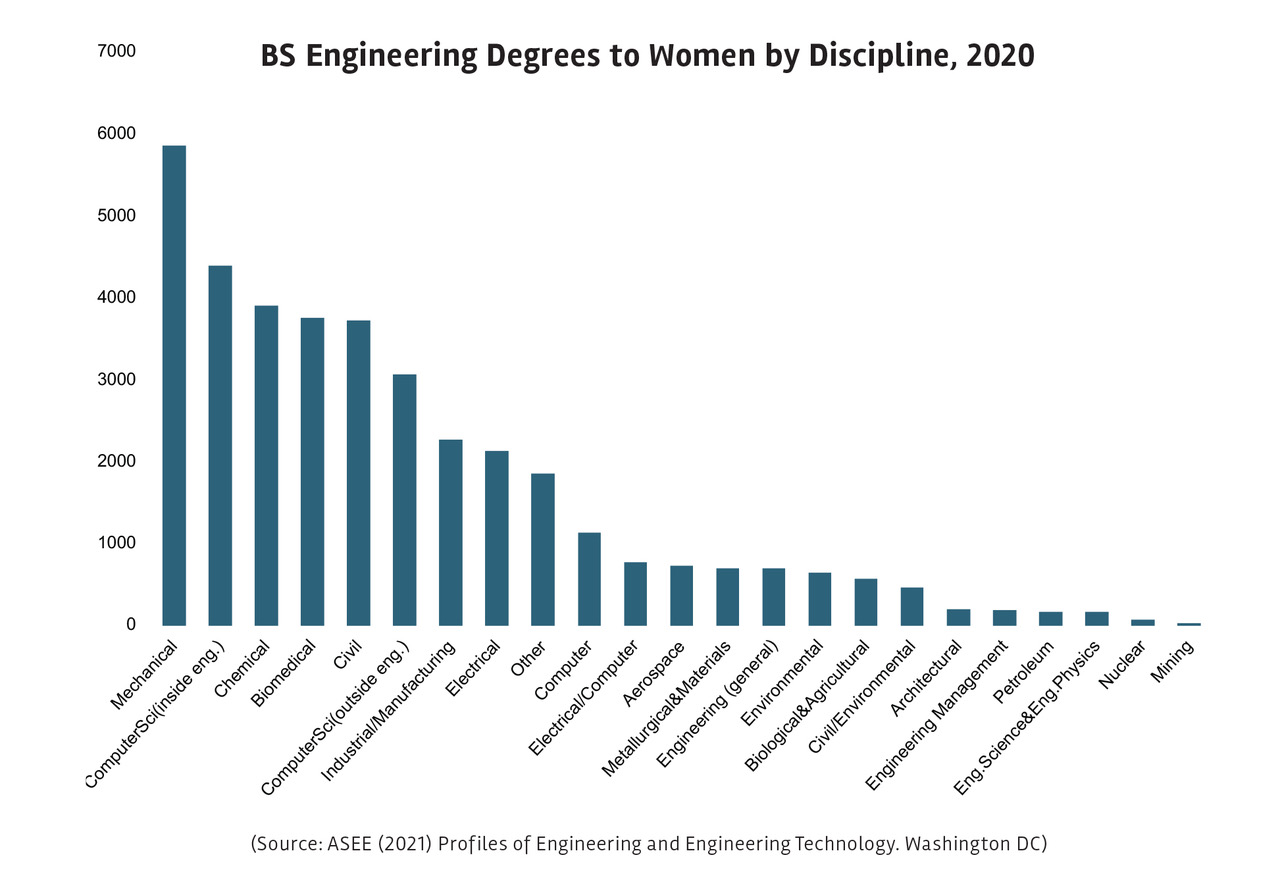

The only discipline to achieve parity in degrees earned is biomedical engineering, with women earning half of the bachelor’s degrees in the field in 2020. That same year, women earned just 16.5% of bachelor’s degrees in mechanical engineering and 37.7% of degrees in chemical engineering, up from 14% and 37%, respectively, in 2002. The report notes that race and ethnicity are also factors among women earning engineering degrees, “although not enormously.” Like degrees earned, women engineering faculty percentages vary by discipline, with about 15% in mechanical and electrical engineering and over 20% in chemical, civil, and biomedical engineering.

Given the relatively stagnant growth in women-earned degrees, Meiksins pondered why women are not pursuing engineering careers. “The discussion always used to be about whether women had the requisite skills to be successful engineers: Were they taking advanced math classes in high school? Were they taking physics and doing the sorts of things that we know predict success in an engineering program?” said Meiksins during the press conference. “The literature has moved away from that argument, not because it was wrong but because the gap between men’s and women’s achievement in fields like math has basically been eliminated.”

Now, “the emphasis on why women don’t choose engineering as a career has shifted from ‘Can they do it?’ to ‘Why aren’t they interested?’” he said. “I think the realization has grown that just telling women what an engineer is and that women can do it isn’t enough. You also have to persuade young women that being an engineer is a way to meet their (life) goals.”

Retaining women

Although the percentage of women earning engineering degrees has increased, many women are not entering or staying in the engineering profession at the same rate. According to the report, when SWE published its first literature review in 2001, women accounted for 11% of the engineering workforce. Eighteen years later, that number had risen to only 14%, indicating that women’s share of engineering employment is substantially lower than their share of engineering degrees.

During the press conference, Rincon pointed out that previous studies have shown that work-life balance is one factor that influences women’s decision to leave engineering employment. Some women leave to care for kids or aging parents, she noted. But it is not the only factor influencing their decision to leave.

“We're seeing a lot of women leaving in midcareer at a higher rate than we see among men in the workplace,” Rincon said. “They are looking for an organization, an employer that appreciates the talents, skills, and experiences that they bring and they offer.” She continued, “We've read some research where women find out … well into their career, they've been with a company for five years, and they realize that they're getting paid less than their male counterpart. … They started on the same day, but he got paid $10,000 more, and over time that just exacerbates the problem and that pay inequity.”

Addressing challenges

Overcoming the hurdles to gender parity in engineering will take concerted efforts throughout the profession. During the press conference, Meiksins noted that men must take action to help make the profession more supportive of women. “The literature has discovered that men are part of this conversation too,” he said. “There’s been a growing sense that women’s ability to effect change … would be helped if men were allies.”

Rincon agreed and said that one concrete step that men and women alike can take is amplifying women’s voices in the workplace. She pointed to an approach that women in government took to repeat ideas that women raised during meetings. “If a woman says something and it is overlooked or ignored, then somebody else at the table is going to speak up and say, ‘Well, Susan had a comment’ or ‘Susan said XYZ before’ or ‘Susan has something to contribute,’” Rincon explained. “It’s about paying attention around the table and noting individuals who are being talked over or ignored and bringing attention to that behavior, so that it doesn’t just continue. You’re calling it out in the moment.”

While a lot of work must be done to bring gender parity to engineering, Rincon is optimistic. “This is just a really ripe time for change,” she said during the press conference.

“We’re seeing a lot of different events, activities, interests, awareness that are aimed at creating a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive place for everyone, whether you’re talking about the workplace or society,” Rincon said. “The greater attention that we’re seeing (to these issues) is something that we need to take advantage of.”