By Jay Landers

Golf courses are highly managed landscapes, requiring constant human intervention to maintain them in the form desired by their users. But what would it take to convert a golf course into a more natural state, one that is resilient to climate change, benefits protected aquatic species, and meets the needs of the human community of which it is a part? A former golf course in Northern California’s Marin County is undergoing just such a conversion, and the process is expected to result in the restoration of critical habitat for imperiled fish species while also providing a key link between multiple existing preservation areas.

Intensive hydrologic work will underpin these efforts.

Significant opportunity

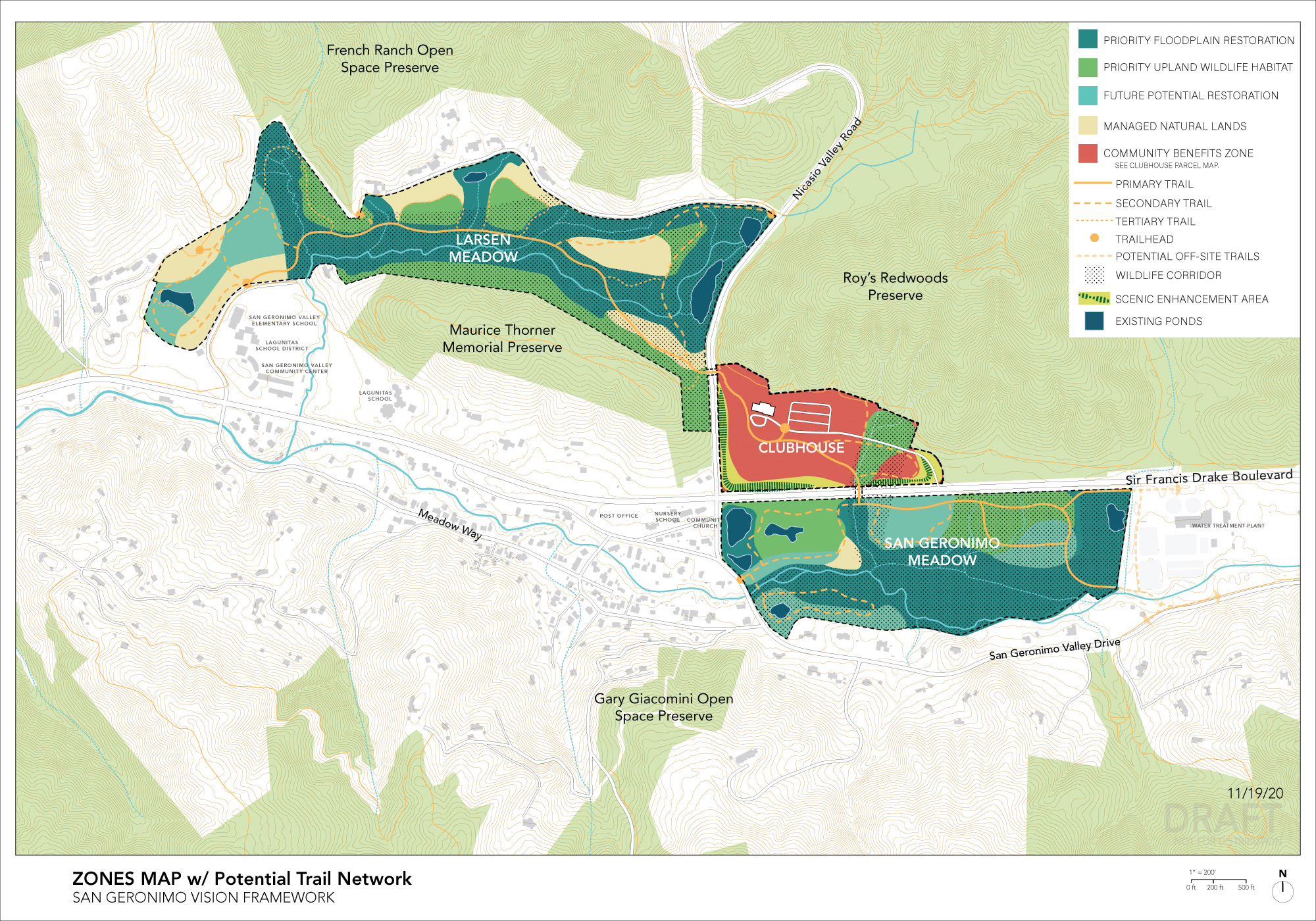

In early 2018, the nonprofit conservation organization Trust for Public Land purchased the 157-acre San Geronimo Golf Course and renamed it the San Geronimo Commons. Constructed in 1965, the 18-hole golf course was situated in what remains a largely rural area within central Marin County and included a clubhouse and a 200-space parking lot. In addition to the 22-acre central parcel where the clubhouse is located, the golf course included a 57-acre front nine and a 78-acre back nine.

The San Geronimo Commons shown in 2018, while it was still a golf course. An area now known as the San Geronimo Meadow appears in the foreground, while an area now known as the Larsen Meadow appears in the distance, beyond the clubhouse. (Artwork by WRT, courtesy of TPL)

As it happens, the property also was home to two waterways — San Geronimo Creek and Larsen Creek — that comprise critical aquatic habitat within the Lagunitas Creek Watershed. The watershed is a key focus of local, state, and federal efforts to protect and conserve two protected fish species, the Central California Coast coho salmon and the Central California Coast steelhead trout.

The presence of San Geronimo Creek, in particular, made the property especially valuable from a preservation perspective, says Anna Halligan, the director of the North Coast Coho Project for the conservation organization Trout Unlimited, which is partnering with TPL to restore the San Geronimo Commons. “The Lagunitas Creek Watershed is a high-priority salmon recovery watershed, and San Geronimo Creek provides roughly 40% of the available spawning habitat” in the entire watershed, Halligan says. The creek segment within the San Geronimo Commons also includes critical, complex rearing habitats for juvenile salmonids.

The size of the property also was a key consideration. “The San Geronimo Commons is one of the largest individual parcels of land adjacent to San Geronimo Creek, and as such it presents a significant conservation opportunity for wildlife and anadromous fish within the high-priority salmon recovery watershed,” Halligan says. “Terrestrial and aquatic wildlife inhabit the creeks and move through their riparian corridors, and endangered and threatened salmonids rely on San Geronimo Creek for spawning and rearing throughout the year. The San Geronimo Creek watershed also provides habitat for up to 12 other special status or listed species.”

Previous disturbance

Although it is the last undammed tributary of Lagunitas Creek, San Geronimo Creek has experienced its share of previous disturbances. “The site has a long history of land use that has resulted in a stream channel that is incised and disconnected from its floodplain,” Halligan says.

An ephemeral waterway that connects to San Geronimo Creek downstream of the Commons, Larsen Creek experienced much more alteration as a result of the golf course’s operations. A significant segment of the creek “was put into pipes and shunted through a series of irrigation pond features” before being returned to its historic channel downstream, says Jorgen Blomberg, the restoration design team director for Environmental Science Associates. The environmental consulting firm is assisting in the development of the restoration plan and leading the technical studies and engineering design for the San Geronimo Commons.

More broadly, the construction and operation of the golf course led to changes in drainage and groundwater conditions on the property. Historically, the site is a “broad alluvial fan formed by a number of distributary ephemeral drainages” that flow from north to south toward San Geronimo Creek, Blomberg says. “The golf course captured a lot of these drainages and concentrated them either in shallow swale features and subdrains across the course or in underground culverts and pipes.”

Another major hydrologic alteration involved the construction of several ponds on the property. Although used by a variety of wildlife, the ponds “function as hot points for invasive species,” Blomberg says. The presence of bullfrogs, bass, and certain aquatic vegetation is particularly troublesome. “All are concerns relative to native amphibians and fish species.”

‘Robust vision’

In 2019, TPL, TU, and ESA — along with the planning and design firm WRT LLC — initiated a two-year process of community engagement to “generate a really robust vision for the property,” says Erica Williams, TPL’s California project manager and San Geronimo field director.

The engagement process found “broad support and enthusiasm in the area” for protecting and restoring open space at the site as well as locating a new Marin County fire station on the property, Williams says.

Local residents also expressed interest in making the site a “community hub,” where people could go for such activities as gatherings, classes, and gardening, she says. A proposed trail network also would facilitate greater recreational access and opportunities for environmental education on the property, which is open to the public.

“Community members are living out the vision every day, using the property’s existing cart paths to connect with one another and with nature,” Williams says. “They have been incredible stewards of the land and partners in planning for the future.”

Multiple challenges

As for the restoration of the physical landscape at the San Geronimo Commons, significant attention will be paid to returning the creeks to conditions that better support protected species while increasing overall resilience of the property to climate change. Chief among the project goals is the restoration of habitat and conditions that support all life stages of the Central California Coast coho salmon, a federally listed endangered species, and the Central California Coast steelhead trout, which is a federally listed threatened species.

Developing a successful restoration project will require addressing multiple challenges, Halligan says. “We need to develop a design that restores ecological processes so that continuous maintenance is not required and that evaluates potential risks to infrastructure and other resources,” she says. “That said, I think one of the biggest challenges we face is developing a design that takes into consideration the impacts of climate change and results in a suite of habitats that provide ecological resilience. For example, salmon need to be able to escape high flows during large weather events, and they need access to deep, cold pools during the hot summers. It can be challenging to develop a design that enhances all these ecological needs.”

The ongoing process of developing a restoration plan for San Geronimo Creek entails analyzing alternatives “to test what options are most appropriate, given what we know about how fish are utilizing the creek on the property at this time, as well as forecasting forward how climate change might influence physical processes within the system, including the sustainability and resilience of those various habitat types,” Blomberg says. TU and ESA are working closely with a technical advisory group composed of local experts and stakeholders to help evaluate project alternatives and guide planning and decision-making.

“We’re looking at how various potential actions to restore the site hydrology — groundwater-surface water interactions, flood plain expansion and connectivity, wetland complexes, etc. — can influence water quality, both in terms of improving temperature, that is, preserving cold water, (and increasing) dissolved oxygen levels,” Blomberg says. “The goal here will be to think about how we can increase the residence time of cold oxygenated water through the rearing period for the young fish; to maintain connected, residual pool habitats; and (to) extend base flows across the study area. Understanding groundwater is a big part of that.”

To this end, piezometers and monitoring wells have been deployed at the site. “We are trying to get a better handle on the seasonality of groundwater, how sensitive the shallow groundwater condition is to rainfall events, and what that interaction is with the base flows of San Geronimo Creek,” Blomberg says.

Daylighting buried channels

Other restoration options under consideration include daylighting the buried section of Larsen Creek. “We’re developing visions and a basis for what a restored channel could look like in terms of habitat function and connectivity, stability, flood conveyance, and as an aesthetic amenity on the property,” Blomberg says.

Similarly, ephemeral drainage features that were buried and shunted off-site to facilitate golf course operations could be restored to the surface. To this end, the team developing the restoration plan is examining the “potential for distributing these flows over the historic alluvial fan to allow for a metering of these flows across the entire landscape,” Blomberg says. This action “could help to support seasonal wetlands (and) more wet meadow type of habitats and to improve overall groundwater conditions.”

Meanwhile, the on-site ponds are being examined for how they might best improve habitat conditions at the site. “We’re evaluating how those ponds might be reconfigured and integrated into the overall restoration plan to become more seasonal-type features that would be supportive of native amphibians and western pond turtles and less desirable for some of the nonnative species that are currently utilizing those features,” Blomberg says.

Of course, fish and amphibians are not the only species of concern that TPL and the restoration team hope to address on the property, which is hemmed in by four other existing Marin County open space preserves. The area is rich with terrestrial wildlife, including mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, deer, and the occasional black bear.

“The San Geronimo Commons property links over 100,000 acres of largely contiguous public open space,” Halligan says. As such, conserving the San Geronimo Commons “provides a unique opportunity to improve wildlife connectivity between key conservation properties,” she says.

Given this strategic location, animal movement across the San Geronimo Commons becomes an important consideration, especially because a major county road bisects the property, Blomberg says. “We’re looking at how different species might use these restored drainage corridors as movement corridors.” To improve safety conditions for wildlife, the restoration plan could include enhancing existing under-crossings beneath the road, including a tunnel once used by golf carts.

Meanwhile, other areas within the former golf course will be restored to more natural conditions as well. For example, former fairways will be converted to such habitats as grassland and oak savanna communities.

Building on previous restoration

Although the development of a restoration plan for the San Geronimo Commons is ongoing, restoration of San Geronimo Creek already has begun. From 2020 to 2021, the nonprofit organization the Salmon Protection and Watershed Network worked with TPL and ESA to remove a failed sheet-pile-and-boulder structure and concrete fish ladder that had been installed decades earlier on a portion of the creek on the property.

“That structure was prone to fish entrapment and blockage from woody debris and other organic material coming down the creek and ultimately didn’t provide for consistent and sustainable fish passage,” Blomberg says.

The structure was removed in 2020 and replaced with a nature-based channel, which consisted of a “roughened boulder ramp that incorporates a series of habitat features and geomorphic channel segments that allow for fish to move effectively through” the point at which the structure had been located, Blomberg says.

Steps also were taken to widen and reconnect the channel with the floodplain. The following year, modifications were made to the waterway upstream of the location of the former fish ladder. Ultimately, 1,700 linear ft of the stream corridor was restored in this fashion. Targeted hydraulic modeling, geomorphic assessments, and stability analyses, along with fish passage criteria, were used to develop the basis for the channel restoration and habitat design elements.

Plans for restoring the rest of the San Geronimo Commons are expected to be completed in 2024, depending on the ultimate scope of the work and funding availability, Blomberg says.

“Trout Unlimited is fundraising for the project by developing proposals for state and federal grant programs as well as private foundations,” Halligan says. “To date, TU’s work has been supported by grants awarded by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and from the Resources Legacy Fund. It’s hard to estimate the total costs of restoration at this time. We expect there will be several phases of construction, and each phase could cost anywhere from $500,000 to several million depending on the complexity and scale.”