By Ray Bert

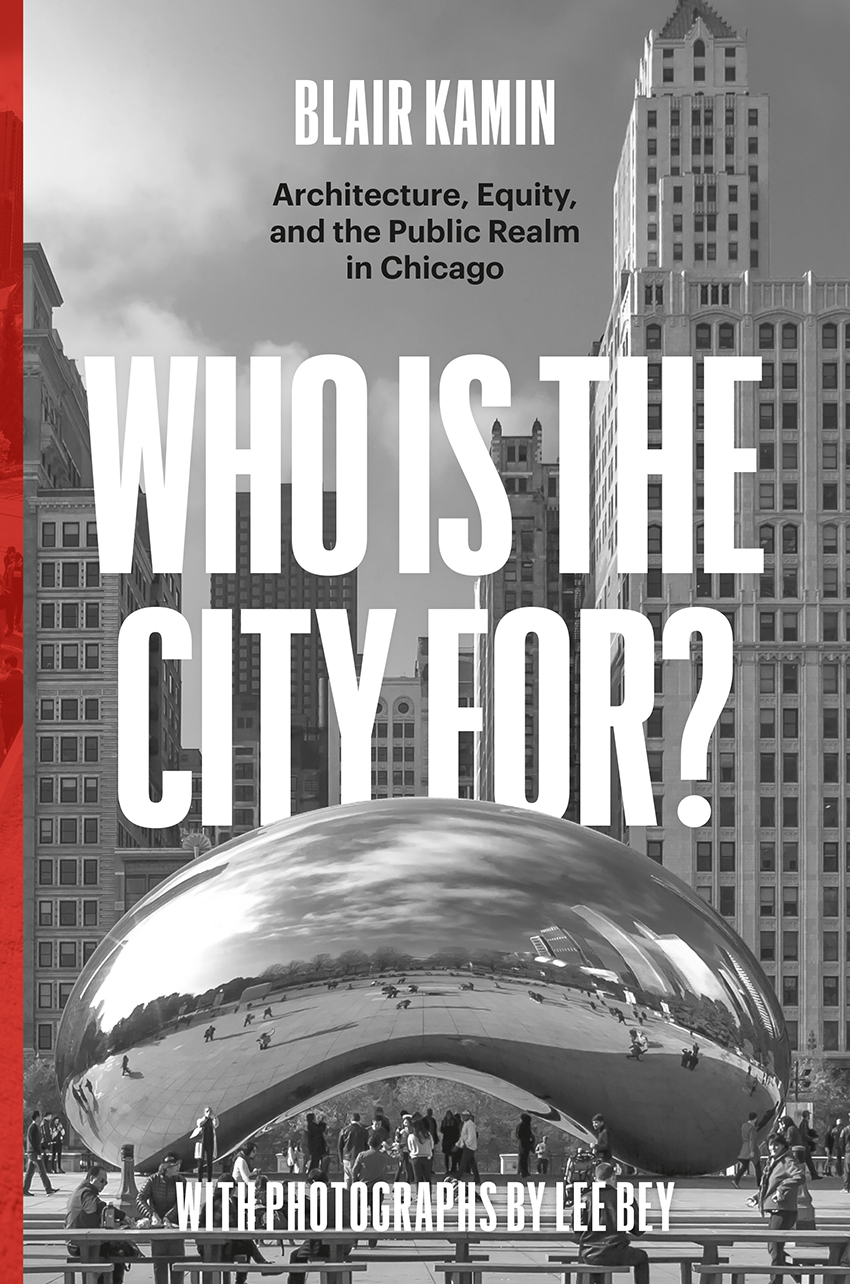

Who is the City For? Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago, by Blair Kamin (with photographs by Lee Bey). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022; 312 pages, $29.

In the Hulu series The Bear, a young chef rising in acclaim in the fine-dining realm drops it all to return to his native Chicago and run his deceased brother’s classic, no-frills beef sandwich shop. Though the show is primarily about family, food, and the pursuit of excellence, we often see, bubbling underneath and occasionally breaking the surface, the authentic-versus-elevated tensions of gentrification and the changing dynamics of a major American city.

In Who is the City For? Blair Kamin — a Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic — tackles another aspect of those tensions from a different angle and in a much more direct way, posing pertinent questions. How to reconcile the increasing opulence of Chicago’s wealthy neighborhoods, dramatic and architecturally iconic skyline, and other trappings of success with its many neighborhoods and residents suffering from years of discrimination and disinvestment? What can the city do to better promote equity, and in particular, how can architecture help achieve that goal?

This book is a collection of Kamin’s Chicago Tribune columns, the third to be collected and published in book form over his long career. Like the previous two, this one covers roughly a decade, in this case from 2011-21, when he left the newspaper after 28 years. Offering the full disclosure one would expect of a respected journalist, Kamin notes that the columns chosen for inclusion have been “tweaked and sharpened” from their original publication and in some cases have had postscripts added.

Further, the author has divided the book into five thematic sections, adding a short introduction to each. The opening section, “Presidents and Their Legacy Projects: Self-Aggrandizing or Civic-Minded?” includes columns critical (albeit in different ways) of the two most recent U.S. presidents. Other sections collect thoughts on urban design and livability, evaluating whether buildings are “good citizens” in their contributions to cities, historic preservation, and, finally, a look at who the city is for and whether it can be made to work better for all its residents, told through the approaches of recent Chicago mayors. The columns within each section contain varied subjects, withering criticisms, credit where it is due, and calls to action — all delivered in crisp, precise, and evocative prose.

Also of note is the photography work of Lee Bey, an architecture critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, in particular since Kamin deemed Bey’s contributions worthy enough to put his name on the book’s cover. Bey’s images of the city appear throughout the book alongside the work of additional photographers.

Opinionated, erudite, and written in a way that will appeal to a larger audience than just architecture and planning experts, Who is the City For? has broad lessons within its pages that apply far beyond the Windy City. Kamin’s answer to his titular question is that even though the realities of our “polarized present” suggest otherwise, “the city ultimately can be a shared enterprise … a glue that binds together an ever-more-fractured society. That’s the inclusive, equity-driven direction we must take as we reconsider and rebuild one of humankind’s great achievements — the city.”

This article is published by Civil Engineering Online.