By Robert L. Reid

A century-old, abandoned hospital in Chicago has been converted into a mixed-use facility as part of a larger, $1 billion redevelopment of the city’s Illinois Medical District. Members of the hospital project’s design team explain their efforts to preserve, restore, and reimagine the historic structure.

A landmark former hospital in Chicago was saved from demolition and transformed into a mixed-use site housing two hotels, medical offices, and various public spaces, including a food court and museum. In the pages that follow, key members of the Chicago-region design team that helped preserve and restore the old hospital discuss their roles in saving this historic site.

These firms include Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which led the design team as the architect of record; Rubinos & Mesia Engineers Inc., the project’s structural engineer; Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc., the facade consultant; and Engage Civil Inc., the civil-site engineer of record.

The general contractor was Walsh Construction, and the developer was Civic Health Development Group.

Located on West Harrison Street in an area known as the Illinois Medical District, west of Chicago’s downtown, Cook County Hospital was completed in 1914. Its campus featured a Beaux Arts-style administration building and four attached pavilions. Designed by Cook County architect Paul Gerhardt and the engineering firm Morey, Newgard & Co., the hospital played an important role for the city of Chicago and in the field of medicine overall, the members of the current renovation project’s design team told Civil Engineering. The hospital’s illustrious history featured many medical advances, including the development of the first blood bank in the United States. The facility was also long known as “Chicago’s Ellis Island” for its devoted treatment of immigrants and disadvantaged communities.

Decommissioned in 2002 following the construction of a new county hospital nearby, the old hospital fell into a severe state of disrepair and was often threatened with demolition. The adjoining pavilions were, in fact, demolished by 2008. But a concerted effort by preservation groups such as Preservation Chicago and Landmarks Illinois managed to save the main building, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.

The restoration and preservation of the old Cook County Hospital building began in 2015 and was completed in the summer of 2020. What follows is the story of how the design team helped save this unique structure, the first project in a roughly $1 billion redevelopment of the overall Illinois Medical District.

Preservation and Renovation

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s efforts to carefully preserve, restore, and adapt the former Cook County Hospital administration building began in the summer of 2015 when SOM led a design-build collaboration with general contractor Walsh Construction.

Designed to meet the changing needs of the neighborhood, the revitalized hospital building features a new Hyatt Place hotel and Hyatt House for extended stays, a food hall, medical offices, community spaces, and a museum dedicated to the hospital’s legacy. The adaptive reuse and restoration of this historic building not only repaired a blighted civic landmark, it also unlocked the area’s potential as the first step in a larger master plan for the Illinois Medical District.

Twin goals

Overall, SOM focused its efforts on two primary goals:

- Maintaining the historic integrity of the building to pay homage to Cook County Hospital’s legacy and history. This included restoring the original terra-cotta facade and detailing the interior — from the marble staircase to the large wood-framed windows and red terrazzo flooring — as well as preserving the building’s overall spatial character.

- Creating new mixed-use, commercial, and communal spaces to support the needs of medical district workers, patients, and patients’ families as well as the surrounding community.

To achieve these twin purposes, SOM altered components of the structure’s interior architecture to better suit the needs of diverse users and create more flexible spaces for occupants, from food hall workers to long-term stay residents at the hotel.

When the rehabilitation construction work began in 2018, the site’s preexisting conditions were atypical of an adaptive reuse project; deferred maintenance, exposure to the elements, and vandalism had caused severe deterioration to the exterior and interior of the building. Previously a beacon of medical care and innovation, the structure had become severely dilapidated. Extensive scanning and documentation of the existing conditions were necessary for the design team to understand what it was working with. This revealed to the team numerous physical challenges, including piles of debris, caved-in floors, and portions of the structure that were unsafe to walk through.

These conditions required extensive removal of the existing life-support, life-safety, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems — all more than a century old. In addition, the team encountered decades’ worth of undocumented infill and modifications to the base building. Still, crews were able to recycle considerable amounts of the removed material, successfully creating six different material streams to divert 98% of this material from landfills.

By carefully renovating the building’s structure, the team was able to preserve many of the building’s most distinctive features, such as the original corridors, which were cleared of infill to allow natural light to fill the space from the windows. As architect of record, SOM oversaw the interior architecture. The exterior restoration work — led by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates — involved repairing the building’s neoclassical-style facade (see “Focused on the Facade").

Interior efforts

Inside the building, SOM returned the lobby to its original height of 25 ft and restored the original red terrazzo flooring and ornate Beaux Arts molding, which evoke the building’s original grandeur. The 106-year-old Tennessee marble staircase was restored, replacing broken or worn treads and pieces from more than a century of foot traffic through the building. The restored wood-framed windows provide expansive views and create a lively atmosphere and a sense of connectedness to the surrounding neighborhood.

A new, sliver-thin canopy of steel and glass marks the entrance to the building, replacing a former bulky addition that had diminished the integrity of the historic facade. Two new exterior entrances were added within existing window openings on the north facade to improve accessibility for tenants and visitors.

Carefully selected contemporary artwork, lighting, and finishes were designed to signal a new chapter in the building’s history. SOM and KOO, the project’s Chicago-based interior designer, took advantage of the building’s relatively narrow footprint to configure 210 hotel rooms filled with natural light. With unique layouts and contemporary art and decor, the rooms provide a rich variety of spaces and views. Some of the more unusual spaces within the former hospital, including lofts above operating rooms with bands of windows on the eighth floor, were transformed into distinctive guest rooms.

In the single basement level, the existing mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems were removed and replaced with state-of-the-art, efficient systems.

Seeking silver

SOM collaborated with engineering firm dbHMS, of Chicago, for concept and schematic designs for the new mechanical systems. The project was designed to achieve a silver certification under the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design rating system, which required the design and construction teams to be diligent in the selection of materials and processes as well as the documentation of construction procedures. Because the hospital was environmentally abated when it was decommissioned in 2002, the only additional abatement required during the renovation project involved the removal of lead paint.

The original building had been uninsulated, which meant that the installation of modern insulation along with new, double-pane windows greatly improved energy usage. But the most critical environmental aspect of the project was simply the reuse of the existing structure itself, which provided the most effective way to reduce the project’s environmental impact and preserve the character and history of the building.

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This article is based on information provided by Adam Semel, AIA, NCARB, a managing partner; Mark Nagis, AIA, LEED AP, a design director; and Ian Kaminski-Coughlin, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C, a project manager associate in the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Focused on the facade

By Rachel Will, P.E.

The structure of the old Cook County Hospital building features structural clay tile cladding for fireproofing with a combination of clay tile arched floors and reinforced-concrete floor slabs. The exterior walls are composed of multi-wythe, header-bonded brick masonry with architectural terra-cotta ornamentation and interior clay tile backup systems. Various combinations of steel beams, plates, angles, bars, rods, and J hooks support the brick and terra-cotta masonry cladding. The building also features limestone at the center balcony and soffits of the north facade and granite at the first floor.

it photo credit]

it photo credit] As the facade consultant on the renovation project, Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc., of Northbrook, Illinois, evaluated the structure’s exterior facade in three phases that commenced in 2011. The initial phase involved a limited visual assessment and preparation of a critical examination report as required by the facade ordinance of Chicago’s Department of Buildings. This phase familiarized WJE with the general construction of the exterior facades.

The second phase included a due diligence investigation requested by the development team to review the existing condition of the facades and uncover the root causes of the major observed distress. This was accomplished through a few limited investigative openings to develop an order-of-magnitude cost estimate associated with the repair options.

The third phase involved a limited investigation for the adaptive reuse project that included materials testing/analysis such as water testing, paint and mortar analysis, repair mock-up trials, and cleaning trials to aid in developing a more accurate and effective facade repair scope.

Deterioration detected

The majority of the terra-cotta units and brick exhibited deterioration consistent with a cladding material that had been in service for more than 100 years and only minimally maintained during the 15-year vacancy preceding the redevelopment project. As expected, weathering and deterioration were most pronounced at locations of unchecked water infiltration, which corroded the support steel, and areas of high exposure. Facade elements that typically exhibited deterioration included the third-floor terra-cotta gutter, projecting balconies, skyward-facing surfaces, parapets, and hung terra-cotta elements.

Previous stabilization efforts and limited masonry and roofing repairs had involved poor-quality replacement materials and poorly detailed installations. As a result, these efforts failed to mitigate the deterioration progression and typically resulted in increased water infiltration. In some cases, distress to the brick and terra cotta was made worse by previous remediation efforts. Most notably, temporary stabilization work involved the installation of ferrous anchors to the face of the terra-cotta units and brick masonry, and an expansive corrosion of these anchors resulted in cracking and spalling of many of the terra-cotta units and brick masonry that otherwise could have been salvaged.

Facade repairs

WJE’s exterior facade repair work began in June 2018 and was completed in March 2020. Major challenges included the extent and severity of the deterioration and the eventual discovery of numerous concealed conditions — caused by the lack of maintenance during the building’s vacancy period — that were not apparent during the earlier limited evaluation of the brick and terra-cotta cladding. Due to an accelerated construction schedule, concurrent repair of multiple exterior envelope elements — including the windows, masonry, and roofing — by multiple subcontractors was required during each phase of the repair work. This presented sequencing and coordination challenges. Typical construction challenges, including inclement weather and repair material lead times, were magnified by the compressed timeline.

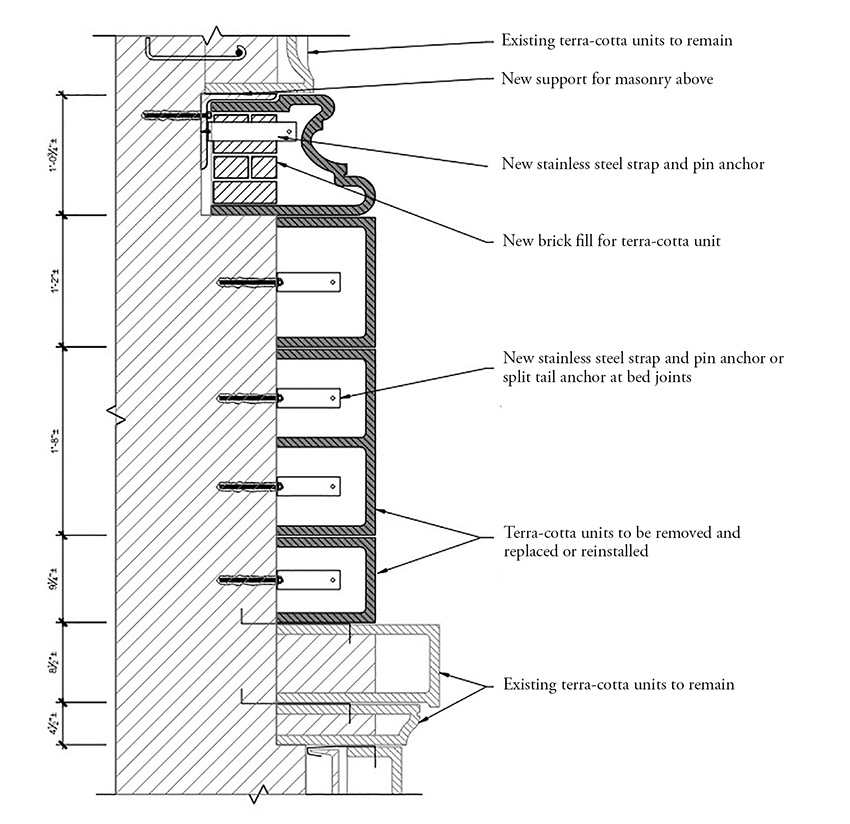

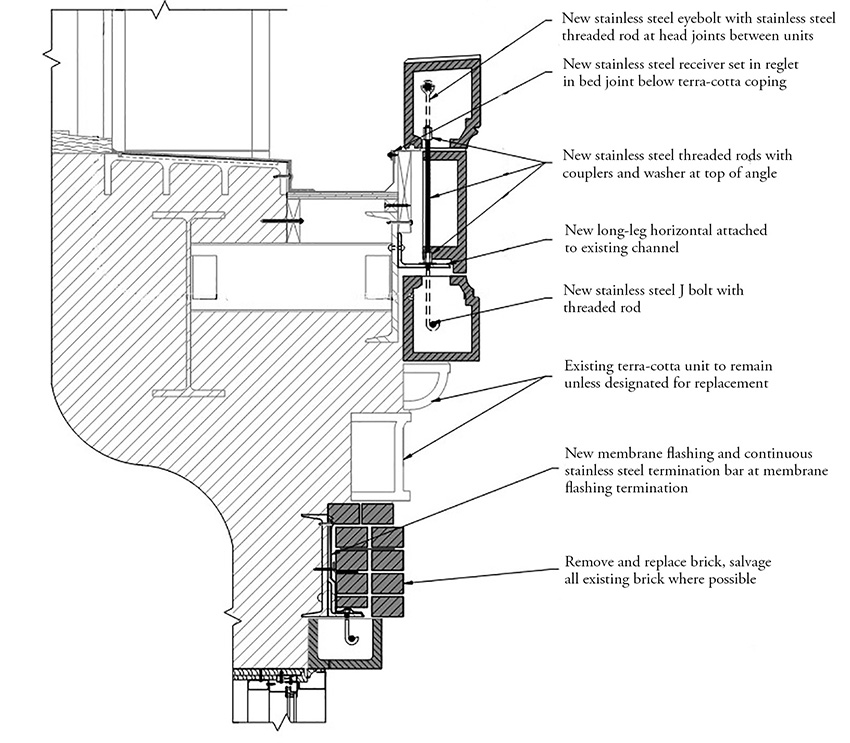

WJE provided design and construction-period services for the masonry subcontractors —Mark1 Restoration, of Dolton, Illinois, and MBB Enterprises, of Chicago — who were responsible for repairing the brick, stone, and terra-cotta masonry on all the building’s facades. This involved the removal of all previously installed temporary stabilization systems and the rebuilding of the outer wythe of brick at the corners, shelf angles, and other distressed locations. Supplemental helical anchors for the brick and terra cotta were installed as needed.

The limestone balconies and soffits were repaired or replaced, and the granite cladding for entrances at the base of building was restored or replaced. Isolated terra-cotta units were removed, replaced, and reinstalled on the basis of their conditions, and large-scale areas of the terra-cotta monumental columns were also rebuilt where necessary.

In-kind replacements

Brick, stone, and terra-cotta units that were deteriorated beyond repair were replaced with in-kind materials: Approximately 10,000 sq ft of bricks were removed and replaced or reinstalled; approximately 4,500 irreparably damaged terra-cotta units were replaced with new units; and approximately 10,000 terra-cotta units were salvaged and reinstalled after the corroded supporting steel elements were repaired.

dit photo credit]

dit photo credit] A terra-cotta gutter at the third floor that is located around most of the building perimeter was also reconstructed. This work included replacing a steel shelf angle and all anchorages, replacing severely deteriorated terra cotta with new terra-cotta units to match the existing units, reinstalling salvaged terra-cotta units, and installing a new gutter liner made of ethylene propylene diene monomer and polymethyl methacrylate.

To help prevent water infiltration, WJE repointed all mortar joints on the north, east, and west facades — which were in the worst shape — and selectively repointed deteriorated mortar joints on the south facade. New roofing made from ethylene propylene diene monomer and polymethyl methacrylate was installed at all roof and balcony areas. A new curtain wall and steep-sloped clad-metal roofing were also installed at the eighth floor to replicate the original operating room skylights.

Certain wood-framed windows that were either missing or deteriorated beyond repair were replaced. The new windows feature aluminum framing that matches the historic windows in configuration, size, and profile. In addition, the monumental wood-framed windows on the north facade at the second and third floors were restored. Finally, along the north, south, and west facades, the project team cleaned the brick, terra-cotta, and stone masonry with a two-part chemical cleaning system.

Rachel Will, P.E., is an associate principal and the associate director of knowledge sharing at Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc., of Northbrook, Illinois.

Securing the structure

By John Belmonte, P.E., S.E., and Farhad Rezai, P.E., S.E.

In May 2016, the design team for the renovation of the Cook County Hospital was given access to the building to evaluate its condition. Chicago-based Rubinos & Mesia Engineers Inc., had joined the project as a subconsultant to Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, serving as the structural engineer of record.

RME assessed the structural integrity of the century-old building’s structural elements, determining the adequacy of framing due to the proposed change in occupancy, the requirements for new openings in the floors, the design of the foundations, and the framing for new elevators. The firm also examined the original elevator shaft floor openings and openings in floors throughout the building. These openings had served multiple purposes when the building was a hospital, including providing space for the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems.

As the project progressed and more areas of the structure became visible, additional structural modifications were designed. Two lower roofs along the south side of the building were also completely demolished, redesigned, and constructed. A new canopy at the north entrance was designed and constructed as well.

Tough environment

Structurally, the primary concern for the building involved its exposure to harmful environmental conditions over the years. To evaluate the existing structural framing, RME needed to examine the framing layout, but the only original construction drawings available were the structural plan and sections of the foundation plus the architectural floor plans. Consequently, RME relied heavily on the site observation visits to obtain the necessary data — a difficult task, given the old building’s lack of utilities for lights and heat.

Because of the historic nature and preservation requirements of the building, RME had to keep demolition for observation purposes to a minimum. Thus, observations focused on the underside of the floor system, which featured structural clay tile arches. Ironically, these observations were assisted by the fact that the building had been abandoned for years and had deteriorated. The plaster on the underside of the clay tiles had fallen, which enabled the engineers to view the tile placement and the location of beams within the clay tile floor. Additionally, zones of flat-arch clay tile had excessive deterioration and were removed, which enabled the engineers to measure the structural floor members in those zones. Connection observations were also made at selective beam and column locations.

Avoiding infiltration

The floor system had been designed to remain within a dry, controlled, temperate environment. It was not supposed to be subjected to freeze-thaw temperatures and water infiltration, as happened. Consequently, the floor areas along the perimeter of the building were damaged and some of the lower sections of the hollow clay tiles and webs had broken away. Because these damaged areas lost their original capacity to support the live and dead loads of the floors, they were removed and replaced with a light-gauge metal deck with concrete topping. The original tie rods remained in place to support the tile arch thrust loads in balance. All other existing structural elements in the floor system were retained.

Because of possible water seepage into elevator pits, several of the existing elevators were abandoned, their pits were infilled, and a concrete slab-on-grade was provided to cover the infill. The elevator shaft floor openings above were infilled with composite light-gauge metal deck plus concrete topping. In certain locations, new elevators were constructed at the sites of the abandoned elevators and the existing floor and shaft framing above were modified to accommodate the new elevators.

The design of all the new elevator pit foundations addressed groundwater concerns and featured water stops. The existing basement walls were also sealed against potential water intrusion.

John Belmonte, P.E., S.E., is a project structural engineer and Farhad Rezai, P.E., S.E., is an executive vice president and principal in charge at Rubinos & Mesia Engineers Inc., of Chicago.

When less is more

By Kelsey A. Taylor

Sometimes the best way civil engineers can be of service is to use as little of a project’s resources as possible — to essentially design the scope of work so that it is relegated to a virtual footnote in the overall project narrative. The goal of the renovation of the historic century-old former Cook County Hospital administration building was to allow the building’s revival to steal the show by transforming the facility into a dual-branded hotel, medical office, and commercial space — all while preserving the intricate exterior and interior architectural features.

As the civil-site engineer of record, Engage Civil Inc. worked with the general contractor, Walsh Construction, to provide critical water and sanitary and storm sewer services to the building while also reconfiguring an existing parking lot and pedestrian walkways — all with as little flash and budgetary impact as possible.

But in the city of Chicago, that can be easier said than done.

Ordinance efforts

In 2008, the hospital building was partially demolished by the removal of its rear wings, leaving just the main 345,000 sq ft structure with an imposing 550 ft long frontage along the moderately trafficked Harrison Street on the Near West Side of Chicago. In place of the rear wings, a parking lot was installed in 2011 under an earlier version of the city’s tough Stormwater Management Ordinance, which requires sites that disturb more than 15,000 sq ft of area to retain the first 1 in. of runoff on-site and to manage a potential 100-year event with detention.

Although the parking lot already provided a significant amount of detention — primarily through a stretch of elliptical pipe measuring 76 in. by 48 in. in cross section — the regulations had become even more stringent since 2011. Thus, the amount of the site being disturbed as part of the renovation again triggered the stormwater ordinance.

Because of the project’s budgetary constraints, Engage Civil worked to use as much of the asphalt parking surface as feasible to minimize the disturbed area that directly correlated to the detention size. The firm also maximized the use of existing detention — already being provided by earlier work at the site — by taking full advantage of the stormwater storage that was allowed above grade as ponding and below grade within crushed stone voids. These efforts ultimately shrank the size of the required new detention system to just a 30 in. diameter concrete pipe measuring 250 ft in length.

Communication and coordination

To service the potable and fire-suppression water demands of the massive building, two new 12 in. diameter water service lines were required. The lines would be fed off the city’s water main, which ran under Harrison Street in front of the building. By a fortunate coincidence, that water main was scheduled to be replaced at around the same time that the renovation work on the Cook County Hospital building was under construction. Encouraged by the close relationship Engage Civil maintains with Chicago’s Department of Water Management, the firm suggested a plan to install the spool pieces for the two water-service valves simultaneously with and in the same location as the city’s new 16 in. diameter water main.

Although that idea may seem like common sense, Engage Civil was warned that many firms had tried to do similar things in the past — but due to the multiple contractors, contracts, departments, and other interested parties involved, this kind of coordination was rarely achieved.

Nevertheless, the effort ultimately succeeded by gently but continuously communicating across the spectrum of stakeholders and repeatedly reminding everyone of the goal. In the end, the spools, valves, and all portions of the new water services located under the roadway were installed before Harrison Street was paved over. This timing was critical to controlling the budget because once the street was paved, it would be placed under moratorium, which in Chicago means that a contractor who wants to cut open a new street must either pay a significant fee or repave a large portion of the street, potentially even the full width of the block in some cases. The rule is designed to prevent a new street from having patches, which are subject to fast decay and potholes in the Chicago winters. Engage Civil’s efforts at communication and coordination helped avoid such a costly scenario.

Kelsey A. Taylor, P.E., LEED AP, is the president of Engage Civil Inc., of Chicago.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: On a personal level, the renovation of the Cook County Hospital building was more than just a typical project for me. An aunt of mine was born in the old hospital building in the 1940s, at a time when nearly all other hospitals in Chicago were segregated by race. As an African American engineer, I was proud to participate in the preservation of a site that had such a legacy of inclusion.

Project Credits

Client: Civic Health Development Group, Chicago

Architect of record and lead designer: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Chicago

Structural and seismic engineering: Rubinos & Mesia Engineers Inc., Chicago

Facade engineer: Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates Inc., Northbrook, Illinois

Civil engineering/infrastructure: Engage Civil Inc., Chicago

General contractor: Walsh Construction, Chicago

Interior design consultant: KOO, Chicago

Landscape architect: Terry Guen Design Associates, Chicago

Sustainability consultant: dbHMS, Chicago

Infrastructure consultant: Level-1 Global Solutions LLC, Chicago

This article first appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Civil Engineering as “From Hospital to Hospitality.”