By Robert L. Reid

A rail line in the United Kingdom that had been closed to regular passenger service since June 1972 is expected to reopen by year’s end, thanks to an innovative piece of machinery that quickly and easily installs railroad ties — called sleepers in the U.K. — onto a prepared track bed and then aligns and secures the tracks to the sleepers.

The Dartmoor Line, in Devon, England, is expected to open for passenger service — provided by the Great Western Railway — sometime before the end of 2021, first with service every two hours and then hourly by May 2022, says Daniel Parkes, ICE, the program director for works delivery at Network Rail.

Network Rail is the owner and manager of most of the infrastructure for Great Britain’s rail network, from tracks and signals to bridges and tunnels, and 20 of the network’s largest railway stations. Train-operating companies, such as GWR, run the trains and lease and manage most of the other stations.

Line evaluation

Located in southwestern England, the Dartmoor Line first opened in 1871, exactly 150 years ago, and operated under various owners until being nationalized in 1948. After Network Rail shut down passenger service on the line, a quarry operator — Aggregate Industries — bought the line to run freight trains. Aggregate also supported heritage train operations on the line and occasional weekend service, according to Dartmoor Line’s website. Together with the Devon County Council and preservation groups, Aggregate also championed the full reopening of the line. In July 2021, Network Rail repurchased the line and part of the Okehampton station from Aggregate and the Devon County Council, respectively.

The Dartmoor Line is expected to be the first project completed as part of the U.K. Department for Transport’s “Restoring Your Railway” initiative, which aims to reinstate local passenger services and restore closed stations.

Part of Network Rail’s Wales & Western region, the Dartmoor Line measures roughly 14 mi in length, from its western end at Okehampton and the nearby quarry to the eastern end at Coleford Junction, at which point it joins the existing Network Rail line to Exeter. The Dartmoor Line was evaluated starting around mid-2020 to determine the feasibility of reopening.

Roughly 3 mi of the line — over several sections — remained in good enough condition, with just minor repairs needed to return those sections to passenger service, Parkes says. The rest of the line, roughly 11 mi over four long sections, was plagued by “very old sleepers, very old rail, (and) very old base plates that weren’t up to modern standards” and had to be replaced, Parkes explains.

Track tech

To do that, Network Rail turned to the New Track Construction machine, a device that can install a maximum of 12 concrete sleepers per minute — a critical tool on a project that ultimately replaced some 24,000 sleepers, Parkes explains. Manufactured by Harsco Rail, headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, the NTC machine used on the Dartmoor Line was owned and operated by the international construction firm Balfour Beatty PLC, which operates the only two such machines currently available in the U.K.

Framed in blue steel and topped by a white gantry unit that slides back and forth across the top of the machine, the NTC functions like “a kind of wheeled factory,” Parkes says. It measures approximately 158 ft long, 13 ft high, and a little more than 9 ft wide, according to the Balfour Beatty NTC User & Information Guide. When combined with more than a dozen freight car wagons that feed new sleepers into the machine, the total NTC train that moves along the line measures more than 1,000 ft in length.

After being towed into position by a locomotive, the self-propelled NTC travels slowly — at just 0.5 mph — along the sets of new rails, which are pre-positioned on either side of a prepared track bed. Using a system of rollers and clamps, the NTC first spreads the rails far enough apart to drop the new sleepers into place — spaced at roughly 24 in. intervals — then pulls the rails into the proper alignment, following a centerline that is spray-painted onto the track bed and monitored via a camera. The system then automatically clips the new rails and new sleepers together.

Key components

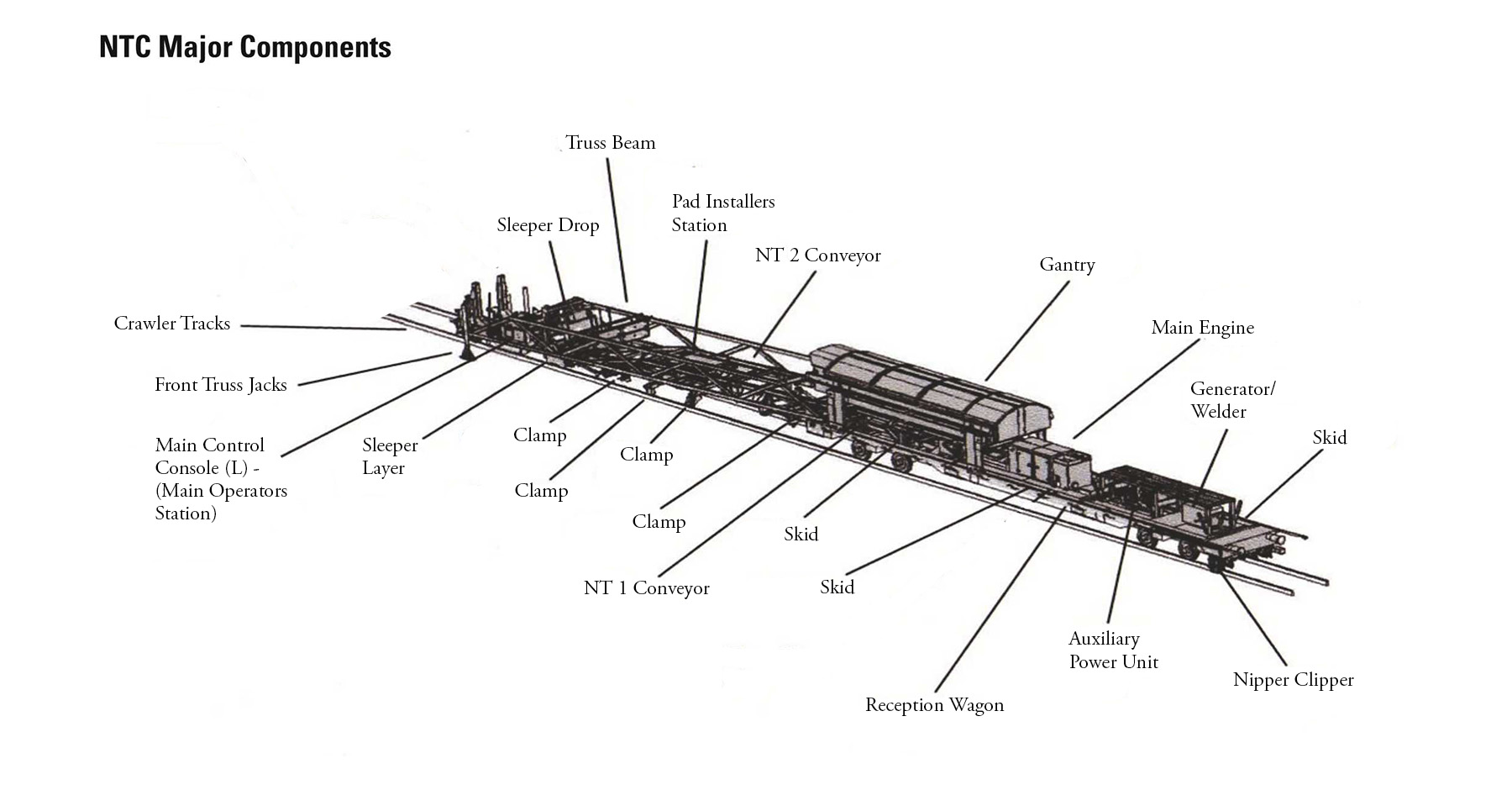

Pulled along by a pair of treads at the front of the machine, the NTC features several key components, as explained in the Balfour Beatty user guide:

- The truss beam, which includes the conveyor system that continuously conveys the sleepers to the front of the machine; the tie-drop system and spacer bar that pick up and place the sleepers onto the track bed ballast in the correct position; the clamps that align the rails and sleepers; and a touch-screen control system.

- The reception wagon, which contains the main and auxiliary engines; a secondary conveyor system that works with the truss beam conveyor; the gantry that shuttles the sleepers from the adjoining freight wagons to the conveyors; the clipping unit; and the machine’s hydraulic and pneumatic equipment and air compressor.

- The power wagon, which includes the engine that generates the hydraulic pressure to provide traction to the NTC, which keeps the machine moving through the work site.

A crew of at least four Balfour Beatty employees is needed to operate the NTC, some of them working from within the machine’s structure.

Although the existing tracks were not suitable for regular passenger travel, they were in good enough condition to move the NTC, the sleeper wagons, and other equipment along the route to access the four sections at which the rails were being replaced, Parkes notes. Before the NTC could start its work, however, Network Rail had to prepare the route by opening the existing drainage channels on each side of the track that had become clogged with dirt and debris from years of no use and no maintenance, Parkes says.

The old rails and sleepers — about 70% of them wood — had to be removed and a bulldozer used to flatten and compact the existing ballast so that the NTC would have a sufficiently firm surface to move across. The new rails were then laid out along the route, which had only limited space on either side of the track bed because it is a single-line route, Parkes says.

Setting a record

The NTC and all the new sleepers were staged from the Okehampton station, which was isolated but preferable to trying to store material at sites along the active Network Rail lines, Parkes says. Towed to the farthest point eastward that needed track replacement, the NTC and a regularly resupplied line of sleeper wagons then worked westward, back toward Okehampton, over a period of four weeks — setting what is believed to be a new record for Network Rail in terms of the most amount of track and sleepers laid in the shortest amount of time, notes Parkes.

After the NTC completed its work, a separate piece of equipment that features vibrating metal rods was used to tamp down the roughly 29,000 tons of new ballast that was installed around and between the new sleepers.

Although Network Rail has used the NTC on previous projects, the Dartmoor Line is by far the longest route and one of the most challenging to rely on the system, Parkes says. He credits the use of the machine with shaving as much as six weeks off the project schedule. Moreover, without the NTC, the work “would have been very difficult, almost impossible,” he adds. For one thing, the new sleepers would have to have been placed all along the route, which had very limited space for storage. “So that would have been very challenging,” Parkes says.

Before the Dartmoor Line reopens, Network Rail also needs to complete certain work at the Okehampton station, including repairs to the station canopy and platform; make drainage improvements; and construct a new surface parking lot. Elsewhere along the route, grade crossings need to be improved. Network Rail also recently completed repairs to an existing bridge along the line, using a 300-ton crane to lift out some of the original timbers and replace them with new steelwork, including transoms and tie bars, so that the crossing can now accommodate the 55-mph speed of passenger trains.

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Civil Engineering as “Track Construction Machine Helps Effort to Reopen Old Rail Line in UK.”