By Laurie A. Shuster

The issue of how civil infrastructure impacts social equity has recently come to the forefront of political and social commentary across the United States. Topics such as environmental justice and equal access to transportation, green spaces, clean water, economic development, and more have emerged as key elements of the Biden administration’s infrastructure plans. (Read “Equity, Environmental Justice Emerge as Key Goals of Biden Infrastructure Plan.”) Discussions have ramped up in many places about the historical injustices to communities of color and communities put at economic disadvantages by infrastructure that has been put in place — as well as how the infrastructure that civil engineers design and build in the future can be rethought to ensure the social, economic, and environmental well-being of all communities that might be affected.

ASCE has acknowledged the importance of social justice in the study and practice of civil engineering by incorporating its tenets into its Code of Ethics, which calls on all members to “acknowledge the diverse historical, social, and cultural needs of the community, and incorporate these considerations in their work,” and to “consider and balance societal, environmental, and economic impacts, along with opportunities for improvement, in their work.”

So ASCE has launched a series of articles, podcasts, and videos on the Source addressing the topic of equity and infrastructure. To add to that discussion, Civil Engineering recently convened a panel of accomplished younger civil engineers to discuss this topic. Their discussion, excerpted in this article, provides a snapshot of how this generation of civil engineers views its role as professionals, educators, and influencers in promoting social, racial, environmental, and economic justice in the communities they serve.

“When I entered the workforce, I was probably a denier that race or other social impacts or considerations even played a role in infrastructure,” said Richard Fernandez, P.E., PMP, ENV SP, M.ASCE, who at the time of the roundtable in mid-August was in the process of trading in his role as project manager with Seattle Public Utilities for that of founder of his own civil engineering consulting firm, Aquario Engineering LLC. Like most civil engineers, he said, he was taught that “meeting the performance requirements of your project and operating within the physical environment and within your budget, that’s what your job is.”

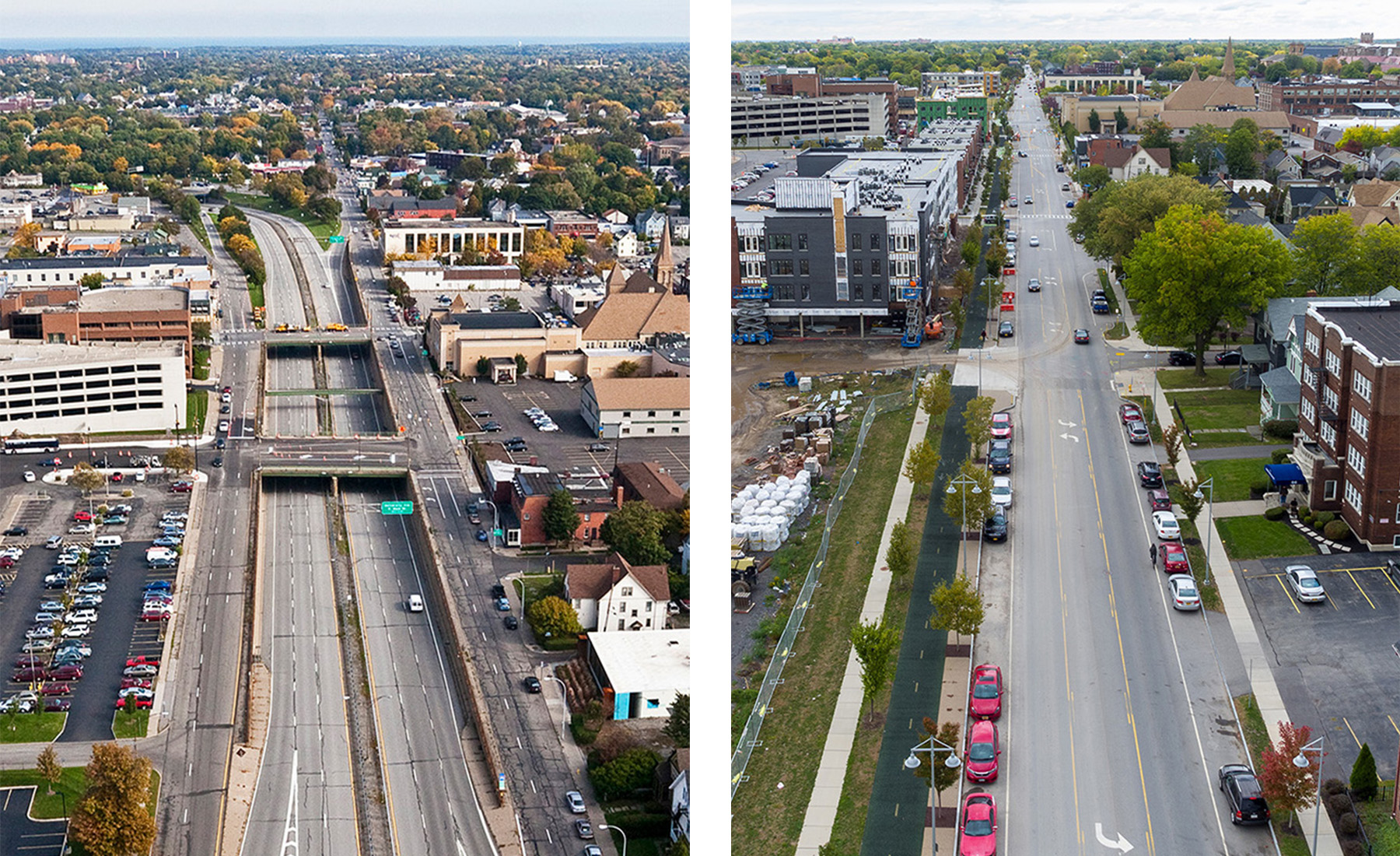

The idea that infrastructure and the profession of civil engineering have played — and continue to play — a critical role in social, racial, economic, and environmental justice is a relatively new concept for many. Yet there is evidence to back up this idea. For many decades in the United States, some of the infrastructure that provided the transportation of goods and people, the delivery of clean water and sanitation, flood protection, and other public benefits has had unintended (and at times very much intended) negative impacts on communities that did not have the financial or political power to fight back. Interstate highways were often built through communities of color, removing housing and businesses and cutting off neighborhoods from economic development. (Read “How the Interstate Highway System Connected — and in Some Cases Segregated — America.”) To this day, expanding those same highways is sometimes seen as a higher priority than offering public transit options that might benefit certain groups more.

Recently, the Federal Highway Administration paused a highway expansion project in Houston to investigate whether it violates the Civil Rights Act. (Read “FHWA Invokes Civil Rights Act to Suspend Houston Interstate Expansion.”) And the expansion of Interstate 710 South in Los Angeles, an important trucking route from the state’s ports toward points inland, has been paused so that the potential air pollution impacts on surrounding, mostly poorer communities can be further studied. (Read about that on the Source using keyword “I-710.”)

And highways are not the only culprits. The Flint, Michigan, water crisis and extreme flooding events from New Orleans to New York City have disproportionately affected poorer communities as well. “You’ll see in almost every city that the biggest flooding issues are in areas that are low income and often minority, and that is not an accident,” Fernandez said, because those are the communities that have historically been least able to fight to stop projects that might have negative impacts on their communities. “I don’t think that the engineers necessarily wanted that, but that was the outcome,” Fernandez acknowledged. “The downstream communities that are located in industrial zones (or poorer communities) end up with these really bad-for-human-health kind of environments at the end of the day.”

Fernandez was by no means alone in the panel in his point of view. “I was the chair for Puerto Rico’s infrastructure report card in 2019,” said Héctor Colón de la Cruz, EIT, A.M.ASCE, a project engineer with O&M Consulting Engineering in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico; the president of ASCE’s Puerto Rico Section; and an ASCE New Face of Civil Engineering — Professional, 2021. “And we could see that the streets in poorer communities are of really poor quality. They get constant flooding; maybe they were poorly designed, or maybe the community was not really able to afford maintenance.

“And there have been some recent studies on how poorer communities are being more affected by climate change than exclusive communities,” Colón de la Cruz continued. “It made me think: How are we going to tackle climate change and community disparity, when right now, we’re sometimes not even doing really good basic work? If we keep walking this path, maybe over the coming years, exclusive communities will get more exclusive, and poorer communities will be worse.”

Starting with education

“This whole discussion about equity, I think, really needs to start with civil engineering education,” said Martin Reyes, P.E., the transportation deputy for Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda L. Solis. “From my personal experience, during my undergraduate and my graduate degrees, I had never even thought about the idea of equity and infrastructure. I think if you don’t understand the sort of structural disinvestment that we’ve seen throughout the country, (like) when it comes to freeway construction going through low-income communities and communities of color, then it’s going to be really difficult to start advocating in a different direction.”

Expecting civil engineers to learn about these topics on their own, while learning the difficult subjects required for a civil engineering degree, may not be reasonable, Reyes said. Universities could do more. “I used to work at the Los Angeles County Public Works, and that is an agency with 4,000 employees and many engineers who do everything from grant writing to preparing planning documents and community outreach in addition to design, construction administration, and project planning,” Reyes said. “For an engineer to be expected to handle all of that plus concepts that are beyond engineering, I think you need an education that sets you up for that.”

Frederick “Freddy” Paige, Ph.D., EIT, A.M.ASCE, is an assistant professor in Virginia Tech’s Vecellio Construction Engineering and Management Program, a research scientist with the Virginia Center for Housing Research, and a member of ASCE’s Members of Society Advancing an Inclusive Culture, known as MOSAIC. He said he does his best to teach the complete background of past infrastructure projects. “In my classes, I go back through history and make sure folks understand the basic principles of some of those projects,” he said. “We call it the ‘modern marvels project.’ We look at the Brooklyn Bridge, the Hoover Dam, etc. And we look at: Who were the key stakeholders? Who were the people involved? What did it take to create this type of infrastructure? And (we look at) the tradeoffs they made. Putting people first, understanding what your goals are, and what you’re putting your time and energy in is what I try to emphasize in my classroom.”

Increasing diversity

Paige said he hoped that topics related to social justice could somehow be built into current civil engineering curricula or learned outside of school, as there is not much room in a typical four-year degree track to add additional courses. “It’s jampacked already,” he said, and the cost of a higher education has only risen lately, sidelining many who would like to enter the field but cannot afford the schooling. “The opportunities to learn this craft are already so exclusive,” he said. “I teach at a public institution in Virginia, and my classes aren’t small — maybe 70-something students. And yet there are rarely more than two Black students in my class. So I’m really big on open-access education for equity.

“I’m not one of the folks championing for our degree to be any longer or more expensive,” he said. “We are discussing the ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology) curriculum right now. And conversations are already very heated.”

Panelists suggested that a more diverse student body might lead to a more diverse workforce, which could, as Fernandez put it, “bake in” a more empathetic approach toward a wide variety of communities.

That effort should probably start early, said Jose Aguilar, P.E., ENV SP, M.ASCE, who is a civil engineer specializing in roadways and aviation with WSP in Tucson, Arizona; president-elect of ASCE’s Arizona Section; and chair of the ASCE Committee on Younger Members. “Something that I truly enjoy doing is going to elementary, middle, and high schools to tell them about engineering. I grew up in a low-income community here in Tucson, and going back to (those schools) just to tell them what it is to be an engineer is the type of thing we need to continue doing so that we can create that diverse group of engineers.” (For an in-depth look at how mentoring students from low-income communities can benefit the profession, read 7 Questions.)

Speaking up

Many panelists said that they had been advocating for the consideration of social equity goals in the planning of infrastructure, with limited success so far. Saki Urushidani, P.E., ENV SP, M.ASCE, is a professional engineer with the City of Springfield, Missouri, in the environmental services department’s water quality division and a member of ASCE’s MOSAIC. She said her department relies mostly on in-house engineers who can have some influence over how money is spent. “I am empowered to insert myself into conversations where I can ask questions about what we are doing about equity and what we can do to include equity in our planning processes,” she said. “I try to bring that in, especially because I am in a very white, straight, cisgender, male-dominated organization as a whole, and especially within engineering. I mean, that’s just the demographic. I am, I think, one of the only women of color among the engineers at my organization.

“So I definitely have been trying to ask a lot of questions about what we are doing and what we can do better to include equity into project planning and master planning. And I get asked: ‘Have we had people call in and complain about this problem?’ And I say, ‘Well, I don’t think that’s necessarily the right way to measure whether something is an issue or not, because some people may not trust the government to call us to report an issue of flooding or whatever it might be. Some people might not know to call the government. Some people might not have the time to call the government, because maybe they’re a single mom and they work two jobs or whatever it is.’

“So it’s (a matter of) challenging your superiors to think differently about the way we’ve been doing things.”

Colón de la Cruz added that when he has asked other engineers “if they take into consideration the environmental harm, the community, and how they are being affected by the infrastructure, they all basically say, ‘No.’

“They say, ‘We’re just serving our client’s needs, and we’re working with the minimum requirements,’ which are the codes and standards and the budgetary needs. And I’m like, ‘Hey, but what about the environmental impacts, the community impacts, how designing this road segregates the communities?’ And these engineers say, ‘Well, that’s actually not my problem. It’s our client’s problem.’”

Peyton Gibson, EIT, A.M.ASCE, is a Fulbright scholar at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, working toward a master’s degree in urban economics and a member of ASCE’s Sustainability Technical Working Group. She has worked with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and served in several ASCE leadership roles. She said that during her career and in her volunteer experiences, she has received pushback from the civil engineering community about centering equity — even from other younger engineers. When suggesting community impact should be considered in a construction project taught to students, she was “absolutely torn apart” she said, adding that she was told she was out of line and that it is “not a good idea” for engineers to highlight reasons why a project is bad for the community. “There is this viewpoint that we’re just ‘instruments of policy,’ here to follow the code,” she said.

If engineers want to change that mindset to one that takes into account the impact of their work on all communities that might be impacted by their work, what can they do?

“I have had recent experiences at O&M Consulting Engineering where I got with my superiors, who are aware of the environment and the society, and (asked them) what we can do,” Colón de la Cruz said. “And sometimes we’re able to mitigate those impacts, even if they were not initially designed for.”

Reyes cited the recent decision to put the I-710 S expansion on hold as a win for community justice. The move came even though “the highway connects the ports with the rest of the country, (and those ports) handle, I think, the majority of the container goods for the entire country,” he said. “So there’s a real economic reason for this project.”

But expanding the highway may not be the best solution, he said, because of pollution from the many trucks that already use it. “The communities along this corridor have been labeled the ‘diesel death zone’ because they have such high, elevated risks of cancer, and they are mostly Black and brown communities and low-income communities. If you expand the freeway, you’re concentrating more cars along this single corridor. You’re going to be increasing the amount of pollution and particulate in these communities, making cancer rates even worse than they are. And you would be displacing hundreds of homes along the corridor in the middle of a housing crisis (in Los Angeles).”

Moreover, Reyes points out, it is unclear if expanding the highway would actually improve congestion or if it would simply lead to more passenger vehicles on the highway. The reason is a concept called “induced demand,” he said, which refers to the idea that “expanding freeways leads to more driving.”

Expanding the highway might lead to more negative health impacts but “won’t necessarily solve the problems that you’re seeking to solve,” he said.

Thinking in new ways

It’s situations like this that call for civil engineers to consider “all the other factors that play into infrastructure and how people actually use that infrastructure,” Reyes said. “We really can’t approach it from a single track anymore.”

Panelists agreed that it is up to civil engineers — individually and collectively — to try to influence the projects they work on and the teams they work with.

“We need to stop looking at things solely from an engineering standpoint,” Gibson said, adding that engineers should begin to integrate the social sciences into the physical ones. She said sometimes the most impressive new technology is not the best option for everyone. One example she gave is the new type of mass transit called the Hyperloop. “Maybe it is a really cool technology, but we shouldn’t just jump on something because it’s the next new thing,” she said. “Sometimes the bus is the best option.”

Reyes agreed. “The average person who uses public transit in Los Angeles makes $18,000 a year,” he said, and therefore may not have as many transportation options as those who make more. “So, when you change a bus route or when you eliminate a bus stop, those (decisions) have significant effects on the people who actually use them. From our standpoint, it might be a minor change, but to them, it can make a whole world of difference.”

Urushidani suggested that civil engineers must “do more than just check the boxes of what’s required by the regulations.

“I think we need to be comfortable doing more than just the bare minimum of meeting requirements by law,” she said.

Getting involved in community outreach programs is another way civil engineers can go beyond the bare minimums, panelists said. “If you go out and do your outreach — and to me, public meetings are really a bare minimum — but if you do that, and the community understands the importance of the project,” Fernandez said, “they may suggest a better option. They live in these spaces every day. They have a better idea than an engineer who lives in another part of town or a neighboring town. Their opinions should have weight. It just makes sense.”

"Policy will only get better when engineers get involved to create holistic solutions." — Jose Aguilar

Aguilar pointed out that engineers must be willing to hear even negative feedback on their plans when they hold community events. “Sometimes you might have people really mad and even yelling at you,” he said, “but it’s important to hear them, and it’s important to see how you can make your design better because ultimately, you’re making a design for people, and those people have opinions. Public involvement is a super important thing that we have to advocate for.”

Understanding policy

Advocating for public involvement and for public policy changes — changes that would put community considerations at the center of infrastructure decisions — are ways all civil engineers can help ensure that the infrastructure they design is truly solving communities’ problems, panelists said. But doing so means first understanding public policy and how local and state governments work.

It’s difficult to know where to start, Gibson acknowledged. “Everything is so siloed and funneled — we have federal-, local-, and state-level things going on all at once.

“But at the end of the day, policy change comes down to political will,” she said. “And what is behind political will is advocates and voters — people showing up to their congressperson’s or, more importantly, to their city council’s offices.”

And civil engineers need to be among those who show up, the panelists said. Paige, for example, recently signed up for ASCE’s Key Contacts program, which connects members to state and federal legislators and helps them advocate for infrastructure investments. “I think a lot can be done, even if you don’t have expertise” in advocacy, he said.

Reyes, who works for an elected official, conceded that having “just a basic understanding of local governance is actually really crucial because it’s the cities and counties that really dictate a lot of your policy around transportation, land use, zoning, housing — all the things that we play an active role in. And I think a lot of (engineers) leave their undergraduate education without that basic understanding: What does a city council do? What does a mayor do? What does a county supervisor do? What involvement do they have with the budget?

“There is so much that an elected official can do in dictating where your money goes, how projects are run, and what kind of priorities are set,” he added. “And I think we really need to express to younger engineers how important that relationship is between the constituent and the elected officials. When your elected official gets involved, if they’re supportive, they can help you find that money to actually make that project be what the community wants.”

Even if working directly in every community that is being impacted is not possible, developing empathy toward people of different backgrounds certainly is.

Aguilar argued that civil engineers should take it even a step further — by running for office themselves. “Policy will only get better when engineers get involved to create holistic solutions,” he said. “I’m shocked that very few engineers hold (public) office positions.”

Urushidani said she is in a unique position, working directly for a city. “I tell myself I am the system. Technically, I should have the ability to change the system. So I would definitely encourage people to, instead of complaining about the system and how broken it is, go work for the system.

“I do find it challenging because I am not necessarily super high up in my hierarchy, but I do the best I can to talk to people who can (help or) talk to people even higher.”

One way civil engineers can help clients and communities find the money to ensure that projects meet the holistic needs of communities may be to tap into set-asides for sustainable design. Many communities will fund sustainable designs that champion a “triple bottom line” of economic, environmental, and social benefits. “One thing that I’ve seen directly impact decisions on a very large project — I’m talking about a $570 million water-quality project — is carve-outs for sustainability,” said Fernandez. “There are explicit policy carve-outs for social impacts that bring other benefits to your project and to that community.”

Acting together and apart

What can civil engineers, individually and collectively, do to ensure that the projects that get funded, designed, and constructed are the best choices for all the communities that might be impacted by those projects?

Several panelists advocated for the idea of developing empathy for the communities engineers serve. “One of my favorite parts of doing the community engagement work I do is that when I work with folks who have never gotten engineering training, they still teach me incredible things about how to design systems and provide services to their community,” Paige said. “So, I think figuring out how we can connect with each other, person to person,” is critical.

“I think as folks who have engineering (degrees), are a part of ASCE, and have that backing and the resources of our institutions (behind us), we definitely need to think about how we can use all that to a better extent,” Paige continued.

But it’s also important to connect on a one-to-one level, he pointed out. “Even if you take all that away — if all of us lost our degrees and (connection to) ASCE — I still think we could have an incredible impact in communities just by trying to empower them and do the right thing.” Spending time in the communities that are being served is critical, he said. “I think we overlook things because we’re not truly a part of these communities, and we’re asking people instead of being with them.”

Even if working directly in every community that is being impacted is not possible, developing empathy toward people of different backgrounds certainly is, panelists said. “I would ask people to have more empathy when it comes to doing or even not doing something to infrastructure,” Urushidani said. “An example I’m thinking of is when I saw a sidewalk that was broken and uneven. I asked someone (I work with) if we could have one of our crews repair it, and it was just not a priority. I don’t know what went through that person’s head, but what went through my head was, ‘Well, what if that is the way for someone who is in a wheelchair to get to work and that is the only sidewalk that they can take?’ Did we think about that?

“Just putting ourselves in situations that aren’t our situations, whether it’s someone with a disability or someone who is a person of color or whatever, that different lived experience (will take us) outside of what our regular routine is, day in and day out.

“Also, educating ourselves about different types of identities is very important (so that we can) empathize with them and realize the different experiences that they live through because of those identities.”

Colón de la Cruz related a similar experience. “About a month after we released our report card, I was walking on the sidewalk, and this sidewalk had tree roots coming out of it. And there was this woman pushing her stroller, and she literally couldn’t cross (the road), and there was a high volume of vehicles using the road. I had to help her because this sidewalk was all broken up. We need to work beyond our walls and our comfort zones. We need to have empathy with other people.”

Gibson added that when the Americans with Disabilities Act became federal law, cities “started putting curb cuts in the sidewalks for wheelchair users, and it helped everyone. It helps people with strollers, people with suitcases. So, when you focus on equity, it doesn’t just help one population. It’s good for the greater population.” Publishers such as the UX Collective and publications such as the Stanford Social Innovation Review have produced studies on how “the curb-cut effect” can benefit everyone in a community, she explained.

Fernandez and Reyes pointed out that one way to make an impression on other engineers is to use hard evidence. “For me, what’s worked well, especially with the engineering types, has been data,” said Fernandez. “So in the project kickoff phase, bring everybody to the same page (by presenting) quality-of-life metrics.” Such data might include median salaries, employment rates, housing opportunities, health metrics, and more. Once these data are shared, he said, it may be possible to bring all stakeholders to the table and ask, “‘Do you think that data illustrates the need for an equitable approach?’ To me, that’s something that can be done on almost any project and will move the needle to the positive.”

Reyes said the data in a recently released LA Metro study called Understanding How Women Travel made an impression on him. “In LA, women travel more often than men, and they take more public transit trips than men,” he said. “And their trips will inherently look different from men’s because, according to the study, they frequently will have children with them. They’ll have strollers with them. They’ll have groceries with them. And that completely changes how public transit should be designed. It completely changes how your bus shelter should be designed and what kind of safety elements you’re thinking about.

“There was one story in that study,” he continued, “where a woman said she always wore sneakers whenever she took public transit in case she had to run from somebody who was trying to harm her, which is shocking (to me) but I’m sure a relatable sentiment for a lot of (women).” Examples like this speak to why it’s so important to have diversity in the engineering profession itself, panelists said.

For engineers and policymakers, Reyes said, “data can really help. Studies like that really illuminate the challenges that we should be looking at when we’re doing the work we do.”

Assessing the risks

Civil engineers are familiar with the concept of risk assessment when it comes to the infrastructure they design and its intent to solve problems. But what are the risks of ignoring the idea of incorporating community equity into infrastructure planning?

“It’s very clear and in your face,” Paige said, citing the problems with lead in water in Flint, Michigan, and flooding in poorer communities throughout the country during large storms. ”What’s happened all across our country are the risks. I mean, people die, point-blank, period.”

“I would add that status quo is the risk,” Fernandez said. “We know that the impacts are disparate between groups. So that’s a pretty bad risk, right? Like Freddy just pointed out, people are dying.

“That’s why I think — I hope, anyway — that people are on the same (page), that people agree to the premise that change is needed.”

Laurie A. Shuster is the editor in chief of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Civil Engineering as “Social Justice, Equity, and Infrastructure.”