By Robert L. Reid

Civil engineering firms find it difficult to hire and retain the skilled workers they need for all the infrastructure work that is suddenly available. Some firms have to make difficult decisions about what work they can and cannot do.

The problem is clear to many leaders in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry: There simply are not enough engineers to do all the infrastructure work planned or underway in the U.S. This is especially true following the recent influx of hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding over the next several years from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

As explained by ASCE’s 2022 president, Dennis D. Truax, Ph.D., P.E., DEE, D.WRE, F.NSPE, F.ASCE, in his President’s Note in the September/October 2022 issue of Civil Engineering: “The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a need for about 25,000 new civil engineers each year throughout this decade. However, this number is based on the need to replace workers; it does little to consider the impact of the (IIJA) and civil engineers’ roles in its implementation.”

Across the nation, leading civil engineers and human resources managers can point to numerous challenges created by the labor shortage, which vary by firm and region. But one thing most note is that the problem has been a long time coming, dating as far back as the first decade of the century and the Great Recession in 2008-09, which reduced the number of what would today be the most sought-after personnel — midlevel engineers with a decade or more of experience.

Multiple factors lie behind the labor shortage, primarily simple demographics: The baby-boom generation is retiring, and subsequent generations did not have as many children, notes Ken Mika, P.E., M.ASCE, a client manager and the central region area manager in the Green Bay, Wisconsin, office of Tetra Tech.

And within that limited supply of potential engineers, not enough of them earned college degrees in the AEC fields, notes Michelle Perry, the chief human resources officer at the Houston headquarters of Walter P Moore. Students who might otherwise have become civil engineers instead pursued careers in other engineering disciplines or other fields entirely.

The AEC industry “has not done a great job of branding and making it enticing for students to go into this field,” Perry adds.

Julian Anderson, FRICS, the president of North American operations of RLB, a global project management firm that hires civil engineers, architects, quantity surveyors, and others, notes that “anecdotally, people who are smart enough to become engineers are also smart enough in general to do a degree in finance,” he explains.

“And since the construction industry is not the easiest industry in the world or the most lucrative for most people, there’s been a trend toward finance or other things where (potential civil engineers) could make more money a lot more quickly, without the cyclical vagaries of the construction industry to deal with,” Anderson says.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic may also have accelerated the number of experienced civil engineers who decided to retire, some earlier than they might have otherwise, notes John Deerkoski, P.E., M.ASCE, a senior principal and transportation practice co-leader in the New York office of Thornton Tomasetti. “We have seen a bit of a ‘brain drain’ in the industry, especially involving those with experience,” Deerkoski notes.

That loss of skilled engineers due to early retirement — combined with fewer people entering the workforce overall plus the growing number of civil engineering jobs to fill because of increased infrastructure funding — makes attaining “the right staffing levels a little more difficult,” Deerkoski explains.

Finding work but not workers

The labor shortage “is affecting us to the point where we can’t go after all the work we’d like to go after or take on all the work our clients would like us to take on,” says Mika. “There’s plenty of work out there for us to do, but we’re trying to focus on the work we can do best, to provide the best quality of service, and we’re at the point where we’re going to be turning down work because we aren’t able to fully achieve what our clients expect us to achieve.”

Mika’s fellow Badger State civil engineer, John Kissinger, P.E., S.E., M.ASCE, the president and CEO of GRAEF, based in Milwaukee, says the labor shortage “has been our No. 1 problem for a while.” It was most problematic last year when GRAEF found it difficult to hire civil engineers across the board, regardless of experience or areas of expertise. Although Kissinger feels the labor market has improved somewhat over the past six months, he notes there is still difficulty in finding and retaining civil engineers, “and this did limit us quite substantially in our ability to perform work.”

The problem has been particularly troublesome when it interferes with a firm’s longtime clients. “It’s hard to say no to somebody you’ve been working with for a long time. You want to honor that relationship, not send them to someone else,” Kissinger explains. “We definitely had to be more selective in the type of work we’ve taken, and there’ve been some (projects) that have been very stressful to complete because we thought we’d be able to hire more people, but we weren’t.”

John Piombino, the New York City-based head of human resources for the U.S. region at Buro Happold, agrees that the labor situation “ebbs and flows, sometimes better, sometimes worse.” Currently, Piombino says, the problem is “at one of the tougher levels it’s been at in a while,” in part because of the possibility of a recession ahead. “The uncertainty in the economy isn’t helping us,” he explains. “People are hesitant to make a move, so we can get a lot of initial interest (for an open position) ... but then it’s hard to close the deal.”

Competing for talent

For Hollice Stone, P.E., M.ASCE, the president and founder of Stone Security Engineering PC, based in New York City, which focuses on the niche market of blast resistance and security and safety engineering, it has long been a challenge to find civil engineers with the specialized skills her firm requires. The competition for such workers is increasing: In recent years more large engineering firms have been entering her field and even some high-tech firms are interested in the same types of engineers that she would hire, Stone says.

Thus, while demand for the types of services she provides is also increasing, “for every one person we hire, there are more people than ever before” ready to hire the same people, Stone explains.

Civil engineering firms even face increased competition for talent from their own prospective customers, including certain public agencies, notes Mika. More engineers these days are switching from private sector consulting firms to public sector jobs because the change can result in less travel and fewer hours than the often-longer workweeks and time spent on the road that engineers encounter in consulting work, he explains.

At Buro Happold, the firm’s sustainability consulting practice puts it in competition for workers in that specialization not only with other civil engineering firms but also with such deep-pocketed industry giants as Google and Ernst & Young. “Due to the high level of competition, we have to offer other opportunities and benefits to attract those candidates,” Piombino says.

Others note that the labor shortage is forcing civil engineering salaries upward at a time when overall inflation in the economy is already squeezing employers. “We’ve seen offers in the market that we’ve never seen in the past in terms of the amount of money or benefits and other things thrown at people,” notes Perry.

Anderson reports similar trends. “Most engineers are good at math,” he muses, “and they can see that if the consumer price index is at 8%, they need an 8% pay raise just to keep up.” So salaries are rising more quickly than they might have otherwise “because we’re chasing inflation and also trying to keep people happy who could get higher salaries if they went somewhere else,” Anderson explains.

But he expects the upward pressure on salaries to end soon because the clients of civil engineering firms are also feeling the effects of inflation and thus want to pay less for professional services. “So if you’re suddenly paying an engineer 10-15% more, but the client expects to pay 10-15% less, it doesn’t work!” he concludes.

Civil engineering firms must tackle other pressures as well. Some clients, chiefly those in the public sector, are eager to get projects started and completed more quickly, adds Deerkoski. This is especially true for design-build projects that are seen as providing necessary infrastructure improvements and stimulating the economy by quickly putting more people to work.

The problem, however, is that civil engineering firms have little time to develop staffing plans. Projects that might previously have allowed them nine months or so to adjust staffing, hire additional people, and otherwise get ready must now get underway in as little as a month after being awarded, Deerkoski says. “It just makes getting the work done more difficult because we need to do it faster and adjust our workforce more quickly — which can be a challenge when there’s a limited supply of engineers.”

The growth of design-build procurements also means that general contractors are hiring more civil engineers, Deerkoski adds. Although contractors often had a small pool of engineers on staff, many now want to increase that number because their firms are providing more engineering services under design-build contracts. “It’s a shift that makes the consulting team have to fight a little harder for some of those (human) resources,” Deerkoski says.

Countering the shortage

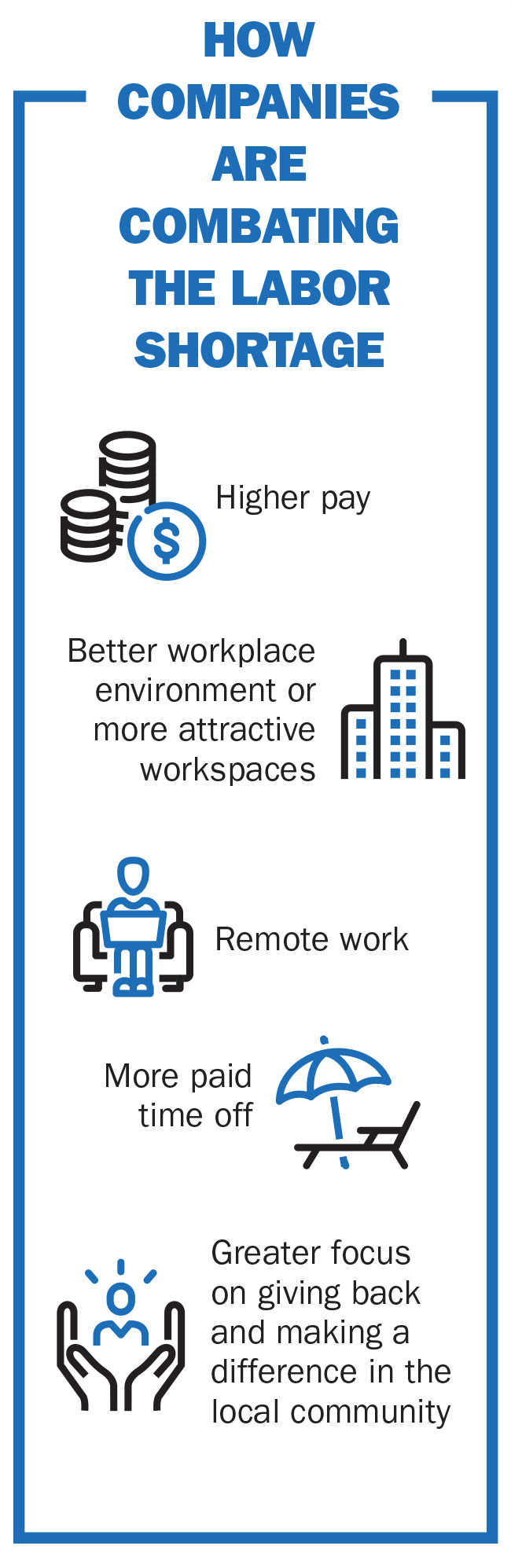

To counter the challenges of the labor shortage, civil engineering firms and other businesses that hire civil engineers are responding in various ways, some traditional, others innovative. Offering higher pay is, of course, one method as well as adding or enhancing benefits. For example, Walter P Moore and Stone Security Engineering have started closing their offices for a week at the end of the year — usually the week between Christmas and New Year’s but possibly the week before Christmas, in Stone Security Engineering’s case.

This weeklong closure is not part of the employees’ annual leave, says Perry. Instead, it’s an extra week of paid time off designed to “better integrate work and life,” she explains.

Some firms offer hiring bonuses and are considering paying relocation costs when hiring people who live in cities or states other than the jobs they will fill.

Stone Security Engineering, which recently started its first 401(k) program, also commenced holding its first all-staff meetings. The company’s 16 employees, who are spread out across the country, working remotely as well as in various offices, now come to a biannual three-day company meeting held on company time.

Employees can bring their spouses to these events, which feature work-related programs as well as fun activities such as a pizza-making course or whiskey tasting, says Stone. The idea is for “everybody to come together and spend time together — especially new hires so they can meet the majority of the team and better understand what we do, since our work is unique,” Stone explains.

The company also holds classes at a testing facility it operates in conjunction with Oregon Ballistic Laboratories. These are fun and informative events that involve “teaching in the morning, blowing stuff up in the afternoon!” Stone notes.

Although Stone Security Engineering has long allowed its employees to work remotely, other firms started doing so during the pandemic. There is, however, a debate within the industry over how much remote work is useful and whether there actually are downsides to the practice (read the sidebar “To work from home or not” ).

For employees who prefer to be in offices, GRAEF has invested heavily in recent years to make its workplaces more attractive, with an award-winning new downtown headquarters in Milwaukee as well as relocations or remodels of many of its branch offices, notes Kissinger.

The firm also emphasizes to its employees its involvement in the community and the good its projects are doing for society “so our employees can see that what we do is really having an effect in the world and in their community,” he notes.

Technology is another way civil engineering firms can help cope with the labor shortage, primarily by enhancing what human engineers can do, not replacing them, notes Deerkoski. “Computers are a powerful tool that helps bring efficiencies,” he explains. “And you need to understand how to use that tool.”

But civil engineers will still need the hands-on experience that comes from “knowing how to build things and get them constructed.”

Firms will still need “to get people in the field to ask: How can you lift that piece or bolt that together?” Deerkoski says. “Can you inspect, clean, and paint it? Can you maintain it easily long term? Does (the design) work technically?” All these different things are very important — “and a computer will never replace all that,” Deerkoski says.

Searching social media

To find new employees, Thornton Tomasetti has a human resources team that in 2018 started approaching potential job candidates via social media, referrals, and other methods, notes Steve Chapman, the firm’s director of talent acquisition. The company posts its job opportunities on the internet and puts together talent pools of potential hires for when it wins new business and needs to increase staffing, Chapman explains.

The firm contacts potential recruits directly but does not reach out to them via their current employers’ email addresses or phone numbers, Chapman adds. His staff members also work closely with Thornton Tomasetti’s internal leadership to make sure they know the hiring needs of managers. The approach seems to be working, Chapman says, pointing out that “our staffing increased 16% last year.”

Large firms with offices around the world can sometimes find the talent they need is already working within the firm — just in another city or country, notes Piombino. Although Buro Happold has not often made such internal transfers, it is an approach the firm hopes to increase going forward. “We’re trying to look more at our global talent and global mobility before trying to fill a position externally,” Piombino explains. “We want to see if there’s someone internally who’d be open to the opportunity” of such transfers.

Making connections

To offset the lack of students pursing civil engineering in college, many firms are reaching out to universities, high schools, and, in some cases, even middle schools to try to boost interest in the field.

WSP USA uses its alumni network “to engage with all our alma maters,” says Lou Cornell, P.E., M.ASCE, the firm’s president and CEO. “We have a great college recruitment team” that focuses on attracting recent graduates and interns who become new hires, Cornell adds. In recent years, WSP USA has doubled the size of its intern program and seeks to convert as many as 80% of those interns into full-time employees going forward, Cornell notes.

GRAEF has long offered college scholarships for students in civil engineering, notes Kissinger, but over the past five or so years it has increased the number and dollar amounts of such assistance. At least one scholarship is targeted at historically underrepresented groups, he adds.

STV recently launched an early career professionals program specifically designed for interns and professionals with five years of work experience or less, explains Jacqueline Opal, STV’s chief people officer. Created through an analysis of labor market data, industry best practices, and STV-specific workforce information, the program includes targeted networking opportunities, training sessions, online learning modules, and in-person events that provide participants with the tools to start and build their careers — from interpersonal skills to conflict resolution, says Opal.

The firm’s intern partner network also connects each intern with a young STV professional, other than the intern’s supervisor, who serves as a guide and mentor throughout the internship, she adds.

Even the competition for interns is getting more intense, notes Mika. Whereas in the past, interns were generally hired during the spring semester for work the following summer, many potential interns are getting offers before Christmas, he notes.

Thornton Tomasetti not only seeks out college-level interns, it also looks for even younger potential engineers. The company was a founding member of the ACE Mentor Program of America, which the program’s website describes as “a free, award-winning, afterschool program designed to attract high school students into pursuing careers in the Architecture, Construction and Engineering industry, including skilled trades.”

Walter P Moore is also a strong advocate of the ACE program and another initiative called Genesys Works. In both programs, Walter P Moore concentrates on providing mentors to high school students primarily from underserved communities, notes Perry. Outreach to high schools is critical, she adds, because “if you try to market and work at the college level, it’s already too late — we need to get more students in the pipeline who want to go into the industry” at the high school level.

Promoting diversity

Various firms report increasing their efforts to connect with students at historically Black colleges and universities and other traditionally underrepresented groups in an attempt to reach a more diverse pool of candidates. At WSP USA, for example, senior executives are encouraged to take leadership roles in various industry associations, giving special attention to ones that represent women and minority engineers, notes Cornell.

The firm has made diversity, equity, and inclusion a “top priority in everything we do, from hiring to training to serving our clients,” Cornell adds. Almost a decade ago, WSP USA established a diversity-focused council that works to “ensure that our leadership team, our employees, our work environment, and our strategies inspire a diverse and inclusive culture across the entire organization and within the communities in which we work,” he says.

More recently, the firm also launched a new initiative, called the WSP Equity Center of Excellence, that serves as the organization’s hub for equity, consolidating and focusing work to develop comprehensive frameworks, policies, processes, and resources that “put equity into action,” Cornell explains.

The new equity center is another opportunity to connect with potential new hires from historically underrepresented groups “to show what we are as an organization and how we can work in our communities to create lasting societal value,” Cornell concludes.

Changing the industry

How long the labor shortage will last is unknown. But its effects are changing the industry and leading civil engineering firms in new directions. One company that generally hires civil engineers with master’s degrees is now willing to consider candidates with just bachelor’s degrees, while another was willing to pay a premium for an applicant with a doctorate because no one with less expensive credentials was available.

At the other end of the educational spectrum, GRAEF worked with a consultant to examine the requirements of certain positions to determine whether those jobs actually needed someone with a college degree. In some cases, they determined that technicians could perform the work previously done by engineers, says Kissinger.

When Tetra Tech was unable to fill some civil engineering technologist positions, the firm turned to geologists. The firm is also considering hiring environmental science majors “due to the lack of entry-level engineers and technologists,” Mika notes.

Likewise, the leadership at RLB questions whether a four-year college degree is always necessary for certain positions. Anderson himself is the product of a professional apprenticeship program from Australia that enabled him to earn his degree as a chartered quantity surveyor — an expert in construction costs — by working days and taking classes at night.

It is an approach that provides the student with experience and an income without accruing the massive student debt that plagues many four-year graduates, he notes. And while RLB has used a similar approach for some of its construction managers, Anderson believes the idea is equally applicable to engineers.

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the May/June 2023 print issue of Civil Engineering as “Help Wanted.”