Courtesy of FireSwarm

Courtesy of FireSwarmThe pieces for automated wildfire suppression are coming together using technology unavailable just a few years ago, bringing to the fore new tools as fire agencies struggle to manage the growing ferocity of wildland fires.

Drone aircraft, both purpose-built and retrofitted, promise to bring resources on-site sooner and safer than their human-piloted counterparts, buying time for human crews to arrive and contain fires.

The growing problem

In the three decades leading up to 2020, the number of homes in the U.S. within the wildland urban interface – the area where human development mixes with undeveloped natural areas – grew by 47%, according to the U.S. Forest Service. While only 9.4% of land in the contiguous U.S. is considered within the WUI, it contains 32% of the nation’s homes. Development within the WUI places people and structures at risk of wildfire, while also complicating wildfire management.

Further reading:

- Monitoring system improves response to fires, other hazards

- After the wildfires: Rebuilding and protecting Los Angeles

- After a storm, send in the drones

Meanwhile, forest fires have increased in intensity and severity as a warming climate creates drier, more flammable vegetation fuels, according to a 2024 paper published in Science. As one measure, wildfire carbon emissions have increased by 60% since 2001.

During 2023, extreme wildfires in Canada released about 640 million metric tons of carbon in five months, more than the fossil fuel emissions of both Russia and Japan for all of 2022, according to a study conducted by NASA.

Ted Carlson

Ted Carlson“The bottom line is that fires are growing so much faster today than they have over the past few decades, and our current response time targets are just too slow for the new reality of these fast-moving fires,” said Maxwell Brodie, CEO of Alameda, California-based Rain, developer of wildfire-containment technology.

The new fire landscape has strained agencies despite their efforts to expand personnel and aircraft resources, opening the field for new, force-multiplying technologies, such as networks of early detection cameras or automated aircraft.

Stationing autonomous aircraft in remote areas dense with wildfire fuel but sparse with humans, such as Canada’s boreal forests, makes them key tools in wildfire mitigation, Brodie says.

“The role of autonomy is to be able to pre-position numerous rapid-response aircraft close to where fires start to reduce the response time,” said Brodie. “We need to go from a 20- or 30-minute response time – in many places across the country, response time is measured in hours – we need to shift that down to sub-10 minutes, very often five or six minutes after a fire starts.”

Alex Deslauriers, founder and CEO of British Columbia-based FireSwarm Solutions Inc., believes that firefighting drones can also step in when conditions might ground human pilots.

“The problem that we see in industry is helicopters are really great at being able to respond to fires, but there are certain scenarios where helicopters are simply not available,” said Deslauriers. “There are not enough resources available, and in a lot of cases, the temperatures or weather conditions or nighttime arise, and then helicopters are simply unsafe to fly around with humans in them.”

Domenico Iannidinardo, CEO of Strategic Natural Resource Group, which supplies wildfire crews to support provincial government firefighting in western Canada, says that many human-caused fires start in the evening or early night. People recreating in the afternoon return to camp with hot vehicles, start campfires or cookfires, and smoke cigarettes.

But human-piloted aircraft must have specially trained pilots and be specially equipped for night missions, which inherently carry greater risk due to reduced visibility.

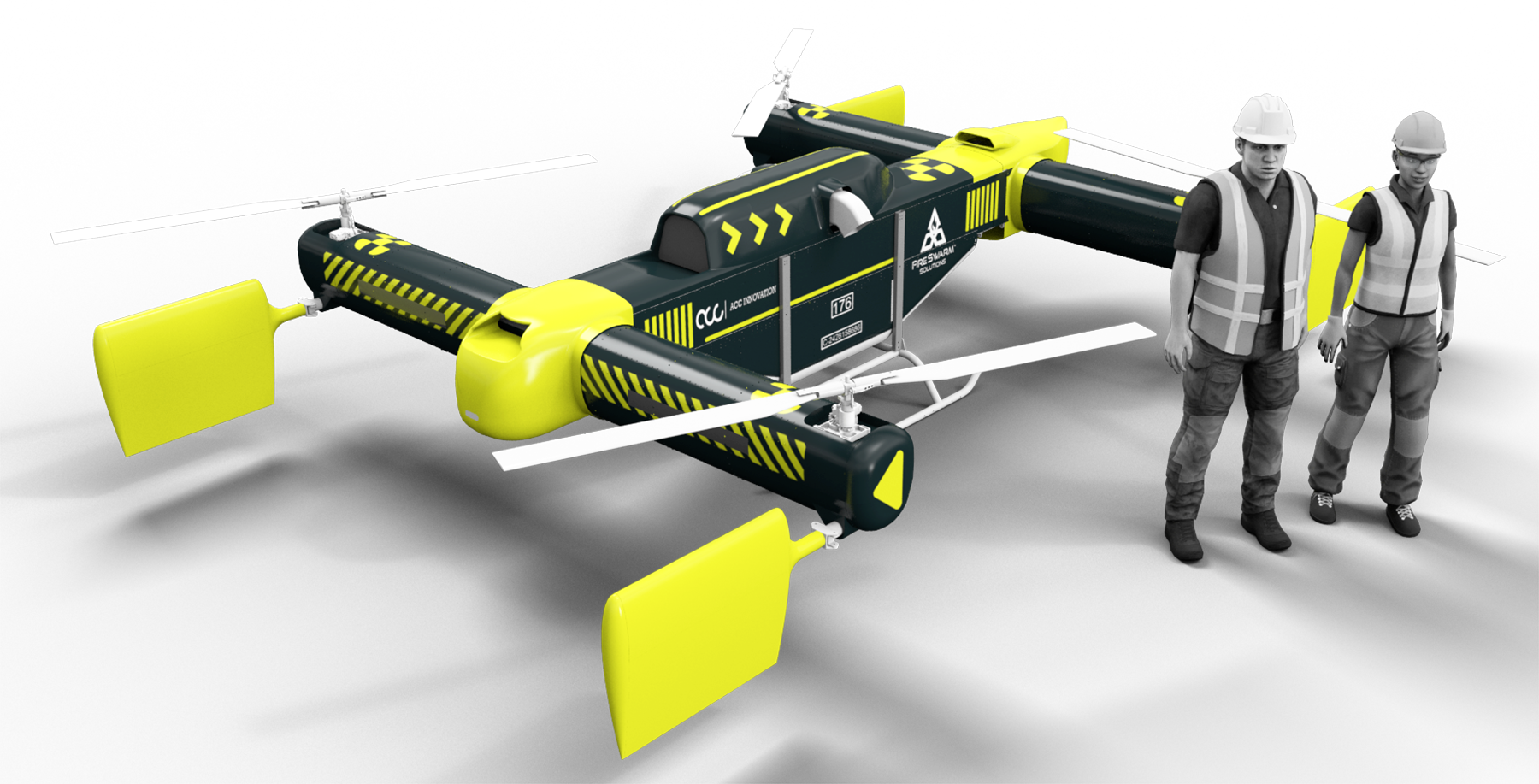

FireSwarm has developed an automated, aerial fire-suppression platform using heavy-lift drones. Equipped with Bambi Buckets, the collapsible water-drop bags strung below firefighting aircraft, FireSwarm drones can plan their own water pickups and water drops, work collaboratively with other assets, and fly through the night or low visibility when humans otherwise would not.

This spring, FireSwarm announced a partnership to aid Strategic’s efforts with FireSwarm drones.

New technologies

The available selection of heavy-lift drones, until a few years ago, consisted only of electric-power drones that were subject to the endurance and payload limitations of batteries, says Deslauriers.

“Even though some of these machines might be able to lift up to 50 pounds, maybe up to 100 pounds in some cases, your endurance is in the 7- to 10-minute range,” he said. “So, from the get-go, as engineers, we knew very early that battery technology is probably 5 to maybe 10 years away from having the energy density equal to that of jet fuel.”

In 2020, Atvidaberg, Sweden-based ACC Innovation began the first test flights of what would become its Thunder Wasp GT heavy-lift quadcopter drone. Powered by a single 220-horsepower turbo-shaft engine, the Thunder Wasp can carry up to 880 pounds and cruise at up to 48 knots. Heavy-lift drones are also finding applications in areas such as wind-turbine repair, heavy construction, and emergency relief.

Deslauriers says the aircraft can operate between 60 and 90 minutes before refueling, although an aircraft’s endurance is a function of factors such as payload, altitude, and wind.

Courtesy of FireSwarm

Courtesy of FireSwarmA partnership between ACC Innovation and FireSwarm, announced in September 2024, marked ACC’s entry into the North American market. ACC has agreed to deliver its Thunder Wasp drones throughout 2025 and 2026.

Retrofits

Rain has taken a different approach, developing software that integrates with aircraft previously designed for humans and transforming them into autonomous firefighting assets. Recent tests with a Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopter demonstrated the promise of the autonomous retrofit.

Unveiled in 2023, Sikorsky Aircraft’s MATRIX technology allows for autonomous and optionally piloted flight of vertical take-off and landing aircraft.

Rain’s software sits on top of MATRIX, providing mission-level firefighting competencies, such as “What is the fire doing, how fast is it spreading, (or) what’s the strategy to engage with it?” said Brodie. “It’s really kind of the difference between the firefighting mindset and the ‘keep the aircraft safe in the air’ mindset.”

In April, the Rain-Sikorsky partnership conducted tests in Southern California.

“(The) California operational environment is complex,” said Brodie. “There’s airspace challenges, there’s rolling hills, and there’s wind conditions. There’s a variety of vegetation. So, really, this put a lot of our systems to the test in a new way, and we’re very happy with the results.”

During the tests, the autonomous helicopter operated alongside other, human-piloted aircraft, demonstrating airspace deconfliction and coordination. Adverse conditions also allowed it to demonstrate water drops in winds exceeding 20 knots and water pickups in winds exceeding 30 knots, expanding the system’s performance envelope.

“(It was) really about showing the technology working in a real-world operational environment,” said Brodie.

The future role of humans

The FireSwarm and Rain teams stressed that their systems act as force multipliers for human operators, allowing humans to do more, and that their technologies cannot yet replace human firefighters.

Courtesy of Rain

Courtesy of RainIannidinardo said that the aircraft remain incapable of helping with the final stages of mop-up or declaring a fire complete. “That’s going to take ground crews and work for the foreseeable future,” he said.

Deslauriers added, “What’s really important to understand is that we are talking about fire suppression here. We are not talking about fire extinction. Fires are extinguished by humans. They are only suppressed by air assets. … The wildfire problem that we are about to face in the next decades is going to require all hands on deck.

“There will not be enough helicopters to address the issues that are going to be facing us this summer and in the summers to come. Bringing simple technology like a heavy-lift drone with autonomy is just another tool that we’re bringing to the market.”