Courtesy of Kiewit

Courtesy of Kiewit Across the United States, data center demand is climbing at a pace that traditional grid planning can’t match.

Artificial intelligence and cloud computing are driving multi-gigawatt expansions in regions where interconnection queues are already stressed, leaving developers in search of reliable, round-the-clock, low-carbon power that doesn’t require hundreds of acres of land.

Further reading:

- As AI, crypto expand, planners aim to make data centers more efficient

- Engineers often need a lot of water to keep data centers cool

- The urgent need for energy infrastructure improvements

That search is bringing nuclear energy, specifically small modular reactors, back into engineering conversations. These factory-built reactors promise compact footprints, high-energy density, and predictable operating costs. And while no data center in the U.S. is yet powered by an SMR, recent licensing developments and nuclear-adjacent projects signal that civil infrastructure teams should begin preparing for this emerging design pathway.

So why are SMRs gaining momentum? What must each engineering discipline consider? And how might a future SMR-enabled digital campus differ from a conventional build?

Why SMRs are suddenly on the table

Tech companies and hyperscale operators are already exploring nuclear options as they look for ways to power the next generation of AI and cloud workloads. In several regions, data centers are growing much faster than the grid can expand, creating multi-gigawatt power needs that are difficult for utilities to meet on current timelines.

Developers want steady, low-carbon power with predictable costs and a small land footprint, but that is becoming harder to achieve through grid interconnections alone.

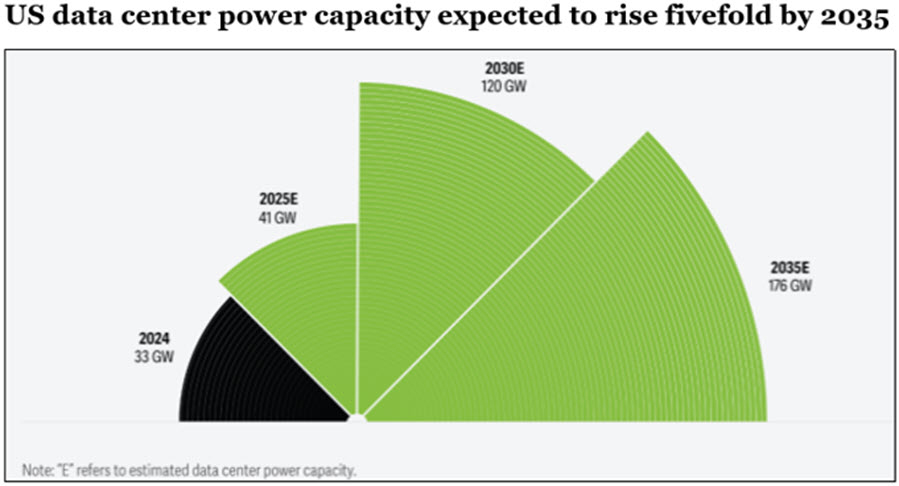

Recent studies highlight the scale of that challenge. A Deloitte analysis projects that by 2035, U.S. data center electricity demand could be many times higher than it is today, adding long-duration gigawatt-level loads in areas where transmission upgrades and new generation are already lagging. That widening gap is one of the major reasons nuclear energy, including SMRs, is returning to serious engineering discussions.

There are already examples of nuclear-powered data centers, even if none use SMRs yet.

Talen Energy’s Cumulus Data campus in Pennsylvania is directly tied to the 2.5-gigawatt Susquehanna nuclear plant, and Amazon has signed large agreements for carbon-free supply from the same station. These projects show that pairing data center campuses with nuclear baseload is achievable and commercially viable.

Momentum on the SMR side is also increasing. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has certified NuScale’s design, and the United Kingdom has selected Rolls-Royce SMR Ltd. to develop its first commercial unit. These developments suggest that SMR-enabled campuses could emerge within the decade.

How should engineers prepare?

SMRs are compact, but integrating them into a data center campus introduces a completely different engineering framework. For engineers across disciplines, the shift is less about unfamiliar physics and more about the standards, processes, and rigor associated with nuclear-grade infrastructure.

Civil/site engineers can:

- Plan campuses and prepare the land. SMR sites are smaller than renewable-plus-storage alternatives, but positioning is far more structured. Expect security setbacks, controlled-access zones, and protected underground corridors for power, cooling water, and communications. Updated federal emergency-preparedness rules allow these layouts to be scaled to SMR risk profiles, offering more flexibility than traditional large-reactor siting.

- Prepare heat rejection and water systems. Depending on whether the design is a light-water SMR, sodium-fast reactor, or high-temperature gas-cooled unit, the ultimate heat sink may be a closed-loop tower, hybrid system, dry-cooling array, or natural water body. Engineers must design heat rejection systems to operate independently for extended mission times, which directly affects basin sizing, redundancy, and makeup-water strategy, especially in arid regions where hybrid or dry cooling becomes essential, according to the NRC.

- Oversee utilities and interconnection. SMRs can be behind-the-meter with a short tie to the data center switchyard, plus a regulated grid intertie for resilience and export. Civil teams should plan for dual-feed arrangements, isolation at points of common coupling, and utility protection schemes harmonized with nuclear plant safety systems and black-start procedures. Industry case commentary from Deloitte and others anticipates this model.

Structural engineers should:

- Be familiar with nuclear-grade design criteria. Safety-related structures must meet the stringent seismic and performance-based requirements applied to nuclear facilities. This includes design and analysis using ASCE 4 and ASCE 43 criteria, very low target probabilities of failure, and performance goals such as essentially elastic behavior during design-basis events. Even nonsafety buildings on the campus must harmonize with these structural expectations.

- Ensure modularization and constructability. Because SMRs are factory fabricated, the site must accommodate heavy-lift logistics, tight tolerances at module interfaces, and embedded steel or composite wall systems that integrate directly with the base mat. Coordination with vendor-supplied layouts and quality-assurance documentation becomes a central part of the structural workflow.

Geotechnical engineers can:

- Prepare for site characterization to nuclear grade. The NRC sets out geological, geophysical, hydrogeologic, and geotechnical programs specifically for nuclear plants, beyond typical industrial sites. Expect denser boring arrays, shear-wave velocity profiling, liquefaction and lateral-spread assessments, faulting evaluations, and justification of site categories for seismic inputs to the nuclear island. Investigations must support safety-related structures, systems, and components and adjacent industrial buildings that house the data center loads.

- Ready foundations and earth structures. Basemat settlements and differential movements must be controlled to stringent nuclear tolerances. Where poor ground exists, anticipate ground improvement with rigorous qualification testing and construction quality assurance under nuclear-grade programs.

Environmental engineers should:

- Consider permitting and the National Environmental Policy Act. Most SMR projects require an NRC licensing process accompanied by a full environmental impact statement. Environmental teams must evaluate aquatic impacts, wetlands, endangered species, and stormwater considerations for the reactor and the data center facilities. New SMR-tailored emergency-preparedness rules allow smaller off-site planning zones, which can simplify cumulative-impact modeling.

- Be familiar with the water, waste, and fuel cycle. Closed-loop cooling can minimize withdrawals, but blowdown still requires discharge permits. Many advanced SMRs use high-assay low-enriched uranium fuel, which is becoming more available but is still developing in supply chain maturity. Environmental engineers must evaluate fuel sourcing, transport, safeguards, and dry-cask storage layouts for spent fuel on campus.

Where do deployments stand?

The closest real-world analog to an SMR data center campus is the Susquehanna-Cumulus model, where a hyperscale facility taps directly into an existing large nuclear plant. Civil teams executed standard data center grading and utilities, while environmental teams leveraged the station’s existing permits for the thermal envelope. This approach avoids SMR-specific licensing but requires proximity to a large operating plant.

Meanwhile, SMR-focused vendors like Oklo are forming partnerships with data center developers and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing firms to integrate nuclear heat and electricity into holistic campus designs. Early projects will depend heavily on licensing progress and fuel availability, but momentum is clearly building.

A plausible SMR-enabled campus

A future SMR-powered data center would look familiar in some ways: rows of data halls, switchyards, and cooling yards. But the surrounding engineering ecosystem would change substantially, including:

- A compact nuclear island supplying firm 24/7 power

- Hardened utility corridors linking the reactor modules to the data center switchyard

- Heat rejection systems sized for long endurance, not just peak cooling load

- Ground improvement and base mat tolerances meeting nuclear quality assurance requirements

- Security-graded perimeters surrounding reactor modules and fuel-handling areas

- Integrated emergency-preparedness and safety-analysis considerations baked into the site plan

For engineering professionals, this means merging industrial campus design with nuclear-class engineering discipline, a combination that is new but well within the reach of multidisciplinary teams.

Several SMR developers have also begun forming engineering, procurement, and construction partnerships for early projects. Announced teams include companies such as Bechtel, Aecon, Kiewit, and Black & Veatch, highlighting how advanced reactors will depend on nuclear-qualified contractors and firms with deep experience in large civil and industrial sites.

So what are the first steps for engineering, procurement, and construction?

- Form a nuclear-capable design team early. Even if the architecture-engineering firm specializes in civil or structural work, partnering with a nuclear architect-engineer is essential.

- Plan dual schedules. SMR construction and data center buildout can proceed in parallel, but interface milestones must be tightly coordinated.

- Optimize cooling for regional constraints. Evaluate wet, hybrid, and dry options early in the site-selection process.

- Treat the geotechnical campaign as a nuclear deliverable. Use nuclear-grade site-characterization frameworks to set acceptance criteria.

- Design electrical systems for flexibility. SMRs support load-following, but their key advantage is firm capacity. Engineers must plan for modular expansion.

- Track vendor ecosystems. Coordinate designs around certified modules and vendor-supplied reference layouts.

How engineers can learn more

The above-referenced NRC emergency-preparedness rule, ASCE 4, ASCE 43, and geotechnical site-characterization guidance are the best starting points for engineering teams. Case studies from nuclear-powered data center campuses, vendor white papers, and Department of Energy fuel-supply programs offer additional context for early adopters.

SMRs will not replace the need for renewables or new transmission, but they could become the anchor technology that supports dense, reliable, low-carbon digital campuses. For civil, structural, geotechnical, and environmental engineers, this shift mainly means applying nuclear-grade discipline to the kind of industrial sites they already know well. As this trend grows, ASCE’s technical committees will likely need to create a manual of practice that addresses the engineering standards and coordination challenges of SMR-enabled data centers.

If you have worked on large energy or utility facilities, you already have most of the skills required. The rest – seismic qualification, nuclear-grade geotechnical investigations, heat rejection systems that can operate for long durations, and site planning that accounts for security – can be learned with the same engineering approach used on any complex project.

Once the first few SMR-powered campuses are built, the process will start looking more familiar. Over time, it is likely to evolve into a repeatable, modular kit of parts, which is exactly what small modular reactors were created to deliver.

Get ready for ASCE2027

Maybe you have big ideas about powering data centers. Maybe you are looking for the right venue to share those big ideas. Maybe you want to get your big ideas in front of leading big thinkers from across the infrastructure space.

Maybe you should share your big ideas at ASCE2027: The Infrastructure and Engineering Experience – a first-of-its-kind event bringing together big thinkers from all across the infrastructure space, March 1-5, 2027, in Philadelphia.

The call for content is open now through March 4. Don’t wait. Get started today!