As an association of, by, and for its members for 173 years, the legacy of the American Society of Civil Engineers is in those members. Their achievements span and enable modern civilization. The roster of members since Nov. 5, 1852, is rich in achievers and their tremendous achievements. In celebration of ASCE Day 2025, Civil Engineering Source has selected five members from across the years to share what made them extraordinary.

photo credit]

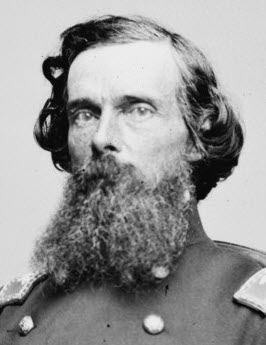

photo credit] Col. Julius Walker Adams

Oct. 18, 1812 – Dec. 13, 1899

After Julius Walker Adams met in 1852 with 11 of his peers in New York City to found the American Society of Civil Engineers and Architects, three years later, he envisioned the need for a bridge spanning the East River between Brooklyn and Manhattan, long before anyone named Roebling was on the scene.

The second cousin of John Quincy Adams studied at the U.S. Military Academy but left after two years to pursue what he already knew to be his calling. He learned engineering from his uncle, George Washington Whistler, and spent the next dozen years working on various railroads, then began building impressive aqueducts, including the record-setting Starrucca Viaduct in Pennsylvania, with James P. Kirkwood. Setting railroads aside in 1856, Adams designed and built Brooklyn, New York’s first large-scale sewer system.

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, Adams was commissioned as a colonel in the Union Army with the First Long Island Volunteers. He was wounded in an 1862 battle at Fair Oaks, Virginia, and returned to Brooklyn. A year later, he helped quell the New York Draft Riots of 1863, defending newspaper offices from angry mobs for publishing the names of those drafted to serve.

After the war ended, Adams resumed his drive for an East River bridge and successfully persuaded construction contractor William C. Kingsley of Kingsley & Keeney to back the project. Adams’ original estimate based on a basic design of his own came in at $5 million, or $99.3 million in 2025 dollars; as designed by John Roebling and built by his son, Washington Roebling and his spouse Emily, the Brooklyn Bridge cost three times the estimate. Adams participated in an official review of the Roebling plans once they were set.

Adams served as ASCE’s 1875 president, and in 1888 was made an Honorary Member, the former designation of Distinguished Member. He died Dec. 13, 1899.

photo credit]

photo credit] Elsie Eaves

May 5, 1898 – March 27, 1983

When Elsie Eaves applied to be a full member of ASCE in 1927, she knew that some women affiliated with ASCE, including Nora Stanton Blatch Barney, had applied for full membership but were declined. Eaves did not let that deter her from pursuing and attaining what she had rightfully earned, as she already had to endure challenges while breaking other glass ceilings across her career.

Eaves’ many accomplishments included creating the first inventory of U.S. municipal and industrial sewage facilities in the 1930s, which helped shape federal loan and grant legislation during the Great Depression. She was the first woman to receive a professional engineer’s license in the state of New York in 1930, but her firsts began much earlier. While attending the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1918, Eaves was elected the first female president of the student engineering society. Then two years later, she became the first woman to earn a civil engineering degree there.

Her first job was a brief tenure with the Bureau of Public Roads’ Denver office, before she was hired by Engineering News-Record, where she reported on monthly construction market and wage report results for 37 years. These reports, read by influential subscribers including government officials, contributed to national planning efforts during the Depression and after World War II.

Eaves went on to become the first female ASCE life member, the first female member of Chi Epsilon, and, in 1957, the first woman member of the American Association of Cost Engineers. She claimed to retire in 1964 but continued advising groups such as the National Commission on Urban Affairs. Eaves died in 1983, and in October 2025, ASCE paid tribute to her by naming its first artificial intelligence assistant “Eaves.”

photo credit]

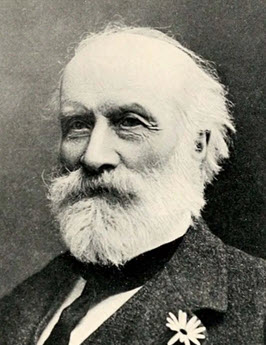

photo credit] Sir Sandford Fleming

Jan. 7, 1827 – July 22, 1915

The ASCE member behind arguably the greatest achievement to get its start at a Society conference – a global system of time zones to enforce consistency – was Canadian, and Scottish by birth.

Sandford Fleming was born Jan. 7, 1827. Like many civil engineers of his time, his work was steeped in the railroad industry, which, as it expanded to networks spanning thousands of miles, struggled with timetables as more than 100 cities established arbitrary yet official time for themselves. Inspiration came in frustration at missing a train while in Ireland.

“The definition of civil time and its scientific determination for railway, telegraph and all ordinary purposes, is a problem to which a solution is imperatively demanded by the present condition of civilization,” set out Fleming in “On Uniform Standard Time, For Railways, Telegraphs And Civil Purposes Generally,” the paper he presented at ASCE’s 13th annual convention in 1881, which happened to be held in Montreal.

“As there can be little doubt that other countries will in due time follow the example of America, it is desirable that we should inaugurate a system which will readily commend itself by its appropriateness and simplicity. One that will have the best prospect of being ultimately adopted throughout the world,” he wrote.

In the paper, Fleming detailed a plan consisting of 24 geographic zones around the globe, divided roughly every 15 degrees of longitude, with hour increments and a “prime meridian” marking the division of the days. The plan included an illustration of the hemispheres with zones marked by letters.

Knighted by Britain’s Queen Victoria, Sir Sandford Fleming is considered historically Canada’s greatest civil engineer, a major force in constructing the nation’s first intercontinental railroad, and in establishing the Canadian Pacific Railway. As chief engineer of the Northern Railway of Canada in 1855, he advocated the construction of iron bridges instead of wood for safety reasons. He was colorblind, yet designed Canada's first postage stamp in 1851, depicting a beaver.

Edit photo credit]

Edit photo credit] Herbert Hoover

Aug. 10, 1874 – Oct. 20, 1964

Herbert Hoover’s place in history is usually considered an ignominious one, based on his response as U.S. president to the Great Depression. Yet, as secretary of commerce under previous presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, Hoover instituted many improvements to then-chaotic street and highway standards, achievements that earned him Honorary Member status from ASCE four years before he was elected president in 1928.

The years following the First World War saw the nation transformed by automobiles. Think of the grainy newsreels of Model Ts being driven haphazardly on unpaved roads that turned into muddy ruts, or of cars dangerously zipping around each other down city streets free of any lane markings, traffic lights, or even stop signs. It really was everyone for themselves.

By the time Hoover convened the First National Conference on Street and Highway Safety in December 1924, the situation had reached crisis proportions. By then, more Americans had been killed in traffic accidents than in battle during WWI; 22,600 alone in 1923, Hoover said. More than 900 representatives of state and municipal police departments, automobile organizations, education groups, construction engineers, and civic groups attended, all agreeing that some form of standardization of traffic laws was needed in the name of safety.

The conference led to developing the first model Uniform Vehicle Code, establishing a set of nationally consistent regulations and ordinances that states and communities could adopt, covering automobiles and their operation, the ways to guide them on the roads they drive upon, and how to enforce these. It was approved in 1926 at Hoover’s second traffic safety conference by the American Bar Association and a panel of commissioners pressing for uniform state laws. Quickly, 34 states adopted the code, either all or in large part.

With frequent updates over the decades to remain relevant, the Uniform Vehicle Code remains current as guidance, a living, lasting legacy of trained civil engineer Herbert Hoover. Today, 49 of 50 states adhere to the code.

Edit photo credit]

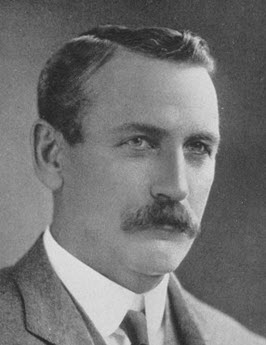

Edit photo credit] John Frank Stevens

April 25, 1853 – June 2, 1943

John Frank Stevens may not have completed the Panama Canal, but as its chief engineer, he established nearly all the processes that successfully built the canal.

Raised in rural Maine, Stevens was a self-taught civil engineer, making a career based on experience earned working for the city engineer of Minneapolis. His ability as a surveyor earned him a job as a locating engineer for the Great Northern Railway, where in 1889, he discovered Marias Pass, Montana, as a suitable route for the rail line to the West Coast. His discovery of a similar pass through the Cascade Range led to it being named for him. Following his promotion to GNR chief engineer in 1895, Stevens built more than 1,000 miles of railroad under his leadership, including the original Cascade Tunnel.

From 1905 to 1907, Stevens served as chief engineer of the Panama Canal. During his tenure, plans for a sea-level canal were abandoned for a system of locks after he persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt. He improved working conditions for canal laborers by eliminating mosquito-borne diseases and built proper living infrastructure. An efficient railroad-supported excavation method he devised removed over 250 million cubic yards of soil. To Roosevelt’s frustration, Stevens resigned once work shifted to actual construction. Although the reasons are unclear, observers believe he viewed the construction phase as not one of his strengths.

After the Panama Canal, Stevens’ career focus returned to railroads. At the request of the U.S. government, he consulted on major rail projects in Russia and Siberia following that country’s 1917 revolution, and in China and Manchuria.

Stevens was ASCE president in 1927 and had been inducted as an Honorary Member in 1922.

Join in celebrating the Society's 173rd anniversary with more features at the official ASCE Day 2025 page.