Claim Reduction is a monthly series by the ASCE Committee on Claims Reduction and Management designed to help engineers learn from problems that others have encountered.

Introduction

The concept of a “standard of care” is central to the professional liability of architects and engineers. While owners often assume that design professionals guarantee flawless projects, the law recognizes that design is an iterative, judgment-based process subject to uncertainty. For this reason, the design professional’s standard of care has historically been defined by reference to what a reasonably prudent professional would do under similar circumstances – not by perfection, nor by hindsight.

This article examines the legal foundations of the standard of care, common contractual risks that can arise when parties attempt to alter or expand it, the treatment of standard of care in widely used industry contract forms, recent legislative protections for design professionals, and practical steps to align risk allocation with insurable coverage and professional responsibility.

1. The common law baseline

The traditional rule is clear: design professionals must exercise the ordinary skill and care of reasonably prudent members of their profession, practicing under similar circumstances and in the same or similar locality.

This “locality rule” has long reflected the reality that design practice varies by region. Codes, construction techniques, climatic conditions, and even customary professional practices differ across jurisdictions. For example, seismic design requirements in California are far more rigorous than in the Midwest; snow and wind load design is critical in northern states but less emphasized in southern climates. A reasonable engineer in Florida would not necessarily be expected to account for heavy snow loads, while that same omission in Minnesota could constitute a departure from professional care.

Locality also shapes the availability of information, technology, and construction methods. A small rural community may not have access to the same testing facilities, specialized contractors, or material suppliers as a major metropolitan area. Courts recognize this and assess performance accordingly. The standard of care is not a national ideal of best practice, but a context-sensitive measure of what is reasonable in the location and conditions where the services are rendered.

Importantly, this locality principle protects both professionals and clients. It ensures that engineers and architects are judged fairly based on what is customary and feasible where they work, while also giving owners confidence that professionals are attuned to the specific environmental, regulatory, and market conditions of their project site.

2. Contractual expansion of duty

While the common law sets a reasonable baseline, contract provisions often attempt to raise or shift the standard of care. Owners and drafters sometimes insert language requiring design professionals to:

- Perform services to the “highest standard of care” or “best practices of the industry”

- Warrant that design documents are “complete, accurate, and free of errors”

- Guarantee compliance with all codes and regulations, sometimes regardless of conflicts or ambiguities

Such clauses are problematic for two reasons. First, they expose the professional to uninsurable risks, since professional liability insurance typically covers negligence (i.e., departures from the ordinary standard of care), not breach of contractual warranties. Second, they create vague obligations that are only defined after the fact, often by an expert hired by the owner in litigation.

The result is a significant mismatch: design professionals may unknowingly agree to duties they cannot realistically meet or insure against. The outcome is increased disputes, strained professional relationships, and potential financial ruin in cases where coverage does not respond.

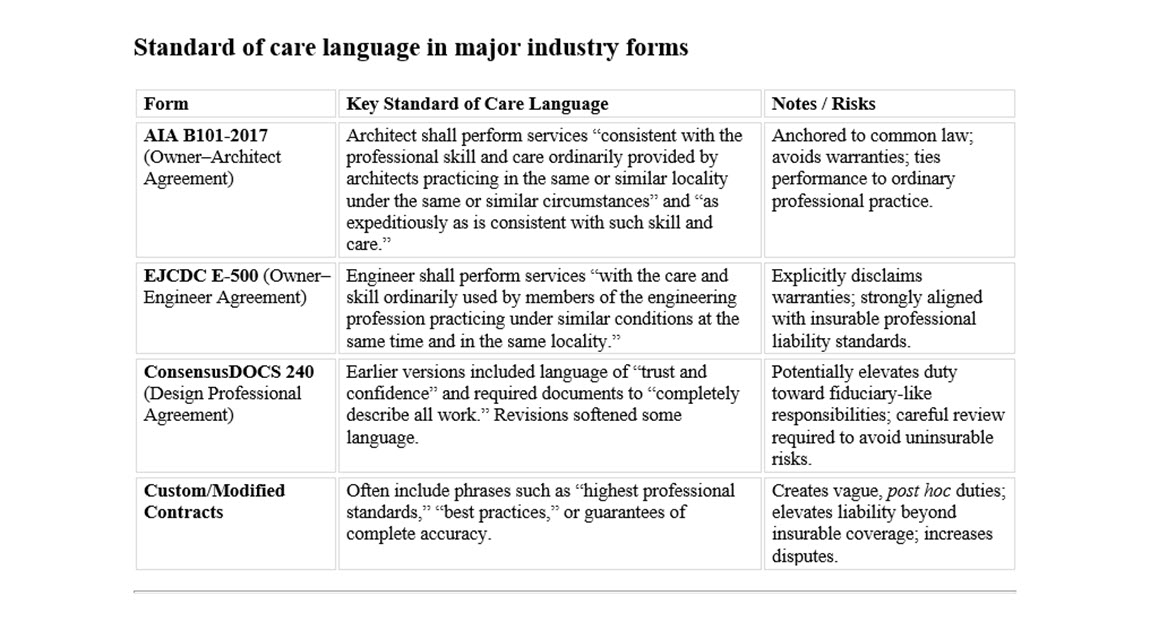

3. Treatment in industry standard forms

Recognizing these risks, professional associations have developed standard-form agreements that preserve the common law definition of standard of care.

The lesson is clear: professional organizations consistently seek to anchor the standard of care to its common law roots, while bespoke or heavily modified contracts often seek to elevate obligations beyond what is reasonable or insurable.

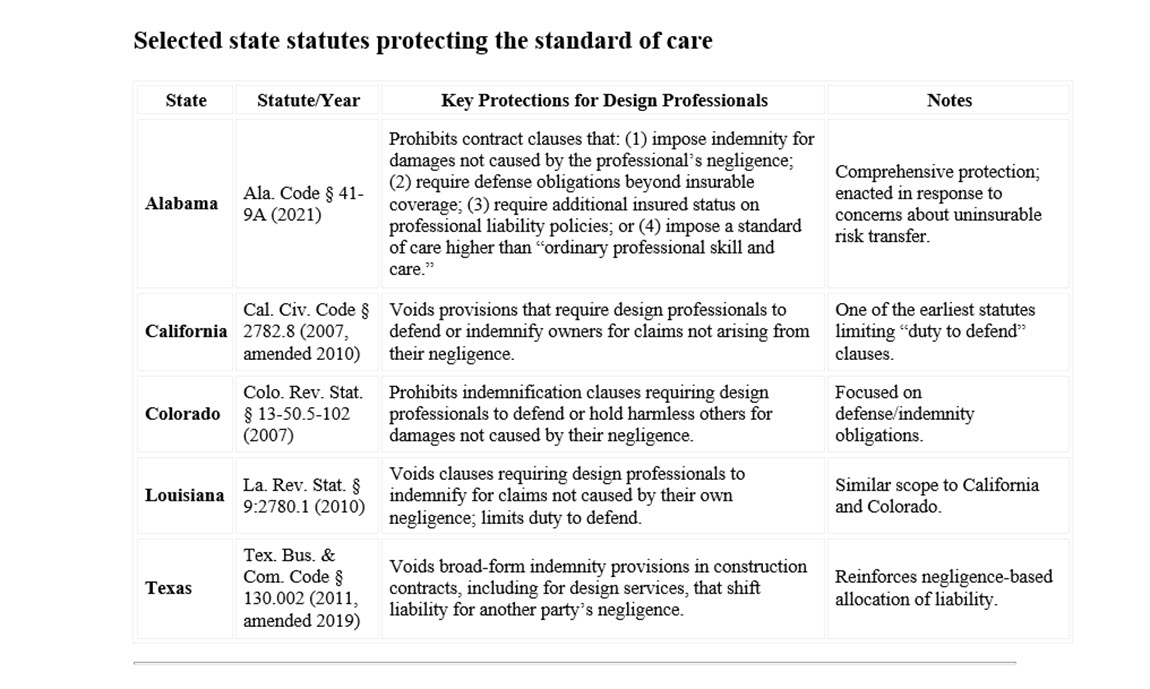

4. Legislative safeguards

Recognizing the inequities created by contract clauses that attempt to alter the standard of care, several states have enacted protective statutes.

For example, Alabama’s 2021 anti-indemnity statute renders unenforceable any provision in a design professional services contract that:

- Requires the professional to indemnify or hold harmless another party for damages not caused by the professional’s negligence

- Requires the professional to defend another party against claims not covered by professional liability insurance

- Requires the professional to list another party as an additional insured on professional liability coverage; or

- Subjects the professional to a standard of care different from ordinary professional skill and care

Similar statutes exist in states such as California, Colorado, and Louisiana, each reflecting a legislative recognition that contracts should not shift uninsurable risks to licensed professionals. These statutes reinforce the principle that negligence, not perfection, is the appropriate basis for liability.

5. Risk allocation and case law lessons

Disputes often arise where contract language conflicts with professional expectations. Courts have generally held that professionals are not liable for every error or omission, but rather for departures from accepted practice. However, where a contract expressly elevates obligations, some courts have enforced the heightened standard, exposing professionals to unanticipated liability.

The key lesson is that words matter. Contractual promises – even if boilerplate – may override the default legal standard. Professionals must therefore scrutinize contracts to ensure alignment with insurable duties. Owners, in turn, should recognize that forcing heightened standards often results in increased fees, reduced competition, and adversarial relationships.

6. Practical guidance for practitioners

To navigate the intersection of law, contracts, and insurance, design professionals should adopt the following best practices:

- Thoughtfully review contracts. Resist language that elevates the standard of care to “highest,” “best,” or “guaranteed.” Replace with common law formulations grounded in reasonableness.

- Use standard forms where possible. AIA and EJCDC agreements provide balanced frameworks widely accepted in the industry. If modified, confirm changes do not alter the insurability of services.

- Engage legal counsel. Professional service agreements should be reviewed by attorneys familiar with construction law and state-specific statutes.

- Educate owners. Many owners do not understand the difference between negligence and warranty liability. Clear explanation helps foster fairer contract terms.

- Monitor legislative developments. State anti-indemnity and standard-of-care statutes are evolving. Professionals should stay informed and advocate for protections that align legal liability with professional reality.

- Document professional judgment. In disputes, liability often turns on whether decisions were consistent with reasonable practice. Clear documentation of assumptions, alternatives considered, and professional rationale strengthens defenses.

7. Conclusion

The standard of care for design professionals remains a cornerstone of professional liability law and contract risk allocation. While owners may seek perfection, the law recognizes that architects and engineers are not guarantors of flawless outcomes. Their duty is to act reasonably, consistent with the skill and judgment of their peers under similar circumstances and in the same or similar locality.

Contract clauses that attempt to elevate this duty introduce uninsurable risks, distort professional relationships, and invite disputes. Industry standard forms and legislative safeguards underscore the importance of preserving the traditional standard of care. Thoughtfully review the contract to confirm your understanding of your risks. Even if you had contracts with the client in the past, they may have inserted new language that wasn’t present in previous agreements.

For design professionals, vigilance in contract negotiation, alignment with industry standards, and proactive education of clients remain essential. For owners, appreciating the realities of professional practice and respecting the balance of risk fosters better collaboration and higher project quality.

In the end, quality in the constructed project – as ASCE has emphasized for decades – is best achieved when each participant fulfills responsibilities consistent with reasonableness, fairness, and professional judgment, not perfection.

Learn more at ASCE’s Risk Management Hub.

Read more helpful insights from the committee’s Claim Reduction series on the Civil Engineering Source.

Want to learn more about risk management? Have thoughts of your own to share? Join the ASCE Community of Practice on Risk Management, where professionals just like you are sharing practical risk management knowledge across multiple disciplines.