Design work recently began on a planned bioenergy facility that will convert biomass into a synthetic gas, combine that gas with pure oxygen in a combustion process similar to that developed by the aerospace industry to propel rockets, and then use the resulting steam to power turbines to generate electricity. Significantly, however, the facility will also capture essentially all carbon dioxide that results from its electricity generation process and sequester it far below-ground.

To be located in the tiny city of Mendota, California, in the state’s Central Valley, the facility is backed by such deep-pocketed investors as the energy giant Chevron Corp. and the tech behemoth Microsoft Corp.

A ‘groundbreaking’ project

In addition to Chevron and Microsoft, the project is being developed by Schlumberger New Energy — a division of the energy-technology provider Schlumberger Ltd. — and Clean Energy Systems, a maker of combustion systems that produce gases for use in electrical power generation or industrial processes. By combining bioenergy production, which uses a product, biomass, that itself absorbs carbon dioxide over its lifetime, with carbon capture and sequestration, the “groundbreaking” project will be “designed to produce carbon negative power,” according to a March 4 news release issued by Chevron, Schlumberger New Energy, and Clean Energy Systems.

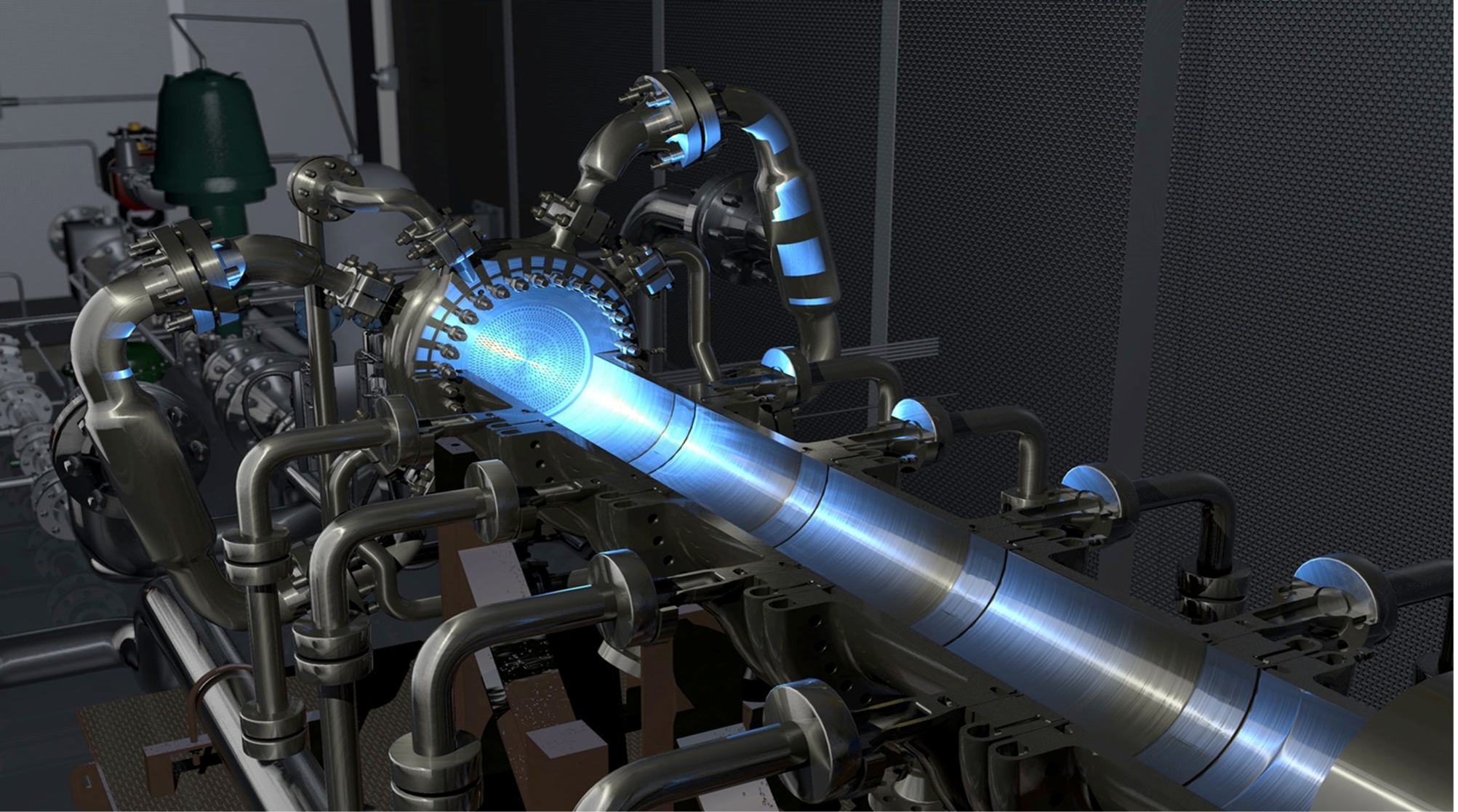

In the first step in the generation process, waste biomass from nearby agricultural operations will be converted into a synthesis gas by means of commercially available gasification equipment and processes, says Rebecca Hollis, the director of business development for Clean Energy Systems. In turn, the gas will be burned with nearly pure oxygen in the company’s proprietary combustion system referred to as both the Oxy-Combustor and as a direct steam generator. Based on rocket-propulsion technology, the oxy-fuel combustion technology produces a “hot drive gas” comprising predominantly steam and carbon dioxide, though other trace elements may be present, Hollis says.

The steam then is used to power turbines, which generate electricity. “After expansion through a power turbine, the steam is cooled and condensed, leaving separate streams of water and carbon dioxide gas,” Hollis notes. Because it uses pure oxygen rather than air, the combustion system does not release nitrogen, unlike typical combustion systems. As a result, the process “leads to cost-effective carbon capture,” Hollis says.

Near total carbon capture

In this way, the planned facility will sequester essentially all carbon dioxide involved with the generation process. “More than 99% of the carbon from the BECCS (bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration) process is expected to be captured for permanent storage by injecting carbon dioxide underground into nearby deep geologic formations,” the release explains. Upon completion, the facility is expected to remove about 300,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year, an amount that is equivalent to the emissions from the electricity used by more than 65,000 U.S. homes, according to the release.

The project entails retrofitting an existing industrial site that once served as a biomass-based power plant. Formerly operated by the waste-to-energy firm Covanta, the facility was idled in 2015, says Sean Comey, a senior adviser for external affairs for Chevron. Given its previous use, the site affords certain benefits, including “usable infrastructure and appropriate zoning,” Comey notes. What is more, the “underlying geology is well suited for permanently storing carbon dioxide,” he says.

The carbon dioxide that is captured as part of the energy generation process will be “stored nearly 10,000 ft below the surface, beneath multiple layers of confining earth,” Comey says.

Improved air quality

By providing an alternative to the practice of open burning of agricultural waste, the facility also could help improve air quality in California’s Central Valley. Expected to use on the order of 200,000 tons of agricultural waste annually, the facility will be equipped with technology that is “designed to operate without routine emissions of nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide, and particulates from combustion produced by conventional biomass plants,” the release states.

Power generated by the turbines will be used to “run the plant and deliver electricity to the electrical grid,” Comey says. “The plant is designed to export about 5 megawatts per hour of electricity (more than 43 gigawatts annually),” he notes.

Modifications to be conducted as part of the project will include integrating the oxy-combustion technology into the existing facility and adding systems for biomass gasification, oxygen supply, and carbon dioxide capture and storage, Hollis says.

Although the companies indicated that they plan to begin engineering and design immediately, they declined to identify the engineering, procurement, and construction firm that has been hired to design the conversion of the existing biomass plant to the BECCS facility. The companies, which also would not reveal the cost of the project, will make a “final investment decision in 2022,” according to the release.

If the project gets the green light and works as planned, it could provide a template for similar carbon-negative energy facilities elsewhere, Comey says. “We believe this project can be a pilot program that could be replicated in other locations to produce energy that also removes greenhouse gases from the atmosphere,” he says.