At the beginning of April, as the COVID-19 pandemic kept many people in their homes and off the roads, hundreds of households in Florida’s Manatee County, near Tampa Bay, were forced to abandon their homes and hit the road — even as some key routes were closed to traffic by the Florida Highway Patrol.

The reason: mandatory evacuation orders from the county government on April 2 that were prompted by fears that leaks discovered in a plastic-lined reservoir at the former Piney Point phosphate plant in northern Manatee County could lead to a catastrophic, uncontrolled release of hundreds of millions of gallons of polluted industrial wastewater. Local and state officials declared a state of emergency in the region, warning of a possible 20 ft high wave of contaminated water that could be released if the walls of the leaking reservoir collapsed. Local residents were moved to hotels outside the danger zone, and even inmates in the county jail were relocated to other correctional facilities in a nearby county.

Then, just days later, the evacuation orders were lifted, roads reopened, and people returned to their homes — thanks in part to rapid action by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Specifically, the Corps used an approach known as rapid inundation mapping, which is designed to improve response times and risk communication planning for flood events.

The Piney Point facility opened in 1966 and closed in 2001. Over the years, the site passed through various owners before being purchased by its current owner, HRK Holdings LLC, of Palmetto, Florida, in 2006. In addition to its phosphate processing past, the site has also been used for disposal of dredged material from work at Port Manatee Harbor. The site is monitored by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and had experienced leaks previously.

Following the discovery on March 26 of the most recent leaks in the plastic-lined gypsum walls that contained the industrial wastewater — the gypsum itself being a byproduct of the former phosphate processing — the county declared a state of emergency on April 1. The state of Florida followed suit on April 3, by which time the reservoir breach was leaking as much as 3 million gal. of water per day, according to updates from the county. To try to prevent a full-scale collapse, more than 30 million gal. of water per day was also being deliberately released from the reservoir and drained into Tampa Bay.

On April 5, three members of the Army Corps arrived on-site “to help assess the situation, provide our expert opinion on what could be done, and address concerns about how immediately (the reservoir) might fail,” says Almur Whiting IV, P.E., the dam safety program manager in the Corps’ Jacksonville District. Whiting and his colleagues — Lt. Col. Joseph M. Sahl, deputy commander of the Jacksonville District, and Samuel Hutsell, P.E., chief of the district’s dams and levees section — examined the site with representatives of the Florida DEP and the Florida Division of Emergency Management.

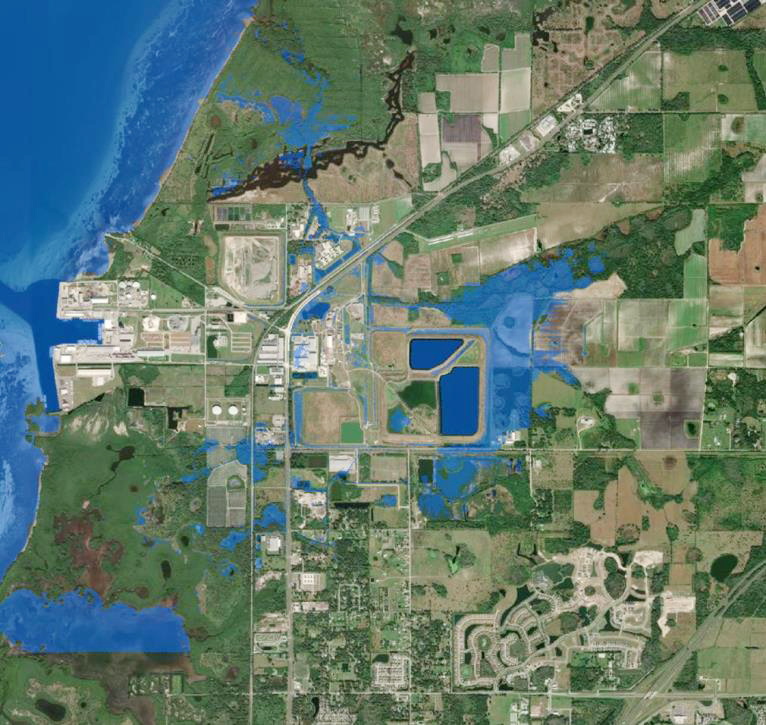

Initially, the state officials were working with older inundation maps, which are used to predict the flooding that could result from a hypothetical failure of dams or other structures. So the Corps offered to create new emergency action plan maps that would be “very specific to this exact situation,” based on the current water levels and surrounding terrain, Whiting says. The new maps would help predict where exactly the water might go, at what velocity, and how deeply it might flood the affected areas.

Normally, such inundation maps take several weeks to complete, Whiting adds. But because of the emergency situation in Manatee County, the Corps’ water resources team within the Jacksonville District “worked around the clock and made (the maps) in 24 hours,” Whiting says. This team included specialists from the Corps’ Modeling, Mapping, and Consequence Center, whose members collaborate online and work in various Corps districts. Several maps were created because “we looked at multiple locations of failure and multiple reservoir levels as the state was actively attempting to lower the reservoir,” Whiting explains.

The maps were created using a software system known as HEC-RAS, developed by the Corps’ Hydrologic Engineering Center in Davis, California.

In addition to facing a time crunch, the Corps mapmakers were also challenged by the gypsum material that formed the Piney Point reservoir, which was not the sort of material the Corps usually encounters for reservoir embankments, Whiting says. So the team had to make some assumptions about how the gypsum might fail, what sort of breach might result, and other factors, Whiting says. The resulting maps were somewhat “scaled down” and “a little rougher” than the typical emergency action plan inundation maps and did initially require a little refining, Whiting concedes. But in the end, the work proved quite beneficial.

The new maps “utilized more detailed and accurate datasets,” which showed “significantly less impacts” in the event of a major breach, explained an April 10 report from the Manatee County Emergency Operations Center. “As a result, all evacuation orders were lifted on April 7.”

The discharges of water from the reservoir ended on April 9, according to the Florida DEP. Divers and submersible cameras were used to locate a seam separation of the plastic liner on the eastern wall of the compartment and steel plating was used to temporarily repair the breach.

As of June, an estimated 201 million gal. of wastewater remained in the NGS-South compartment. The Florida DEP was monitoring and sampling the surrounding waterways and reporting its findings on an interactive water quality dashboard.

The state plans to permanently close and clean up the Piney Point site, using $100 million in federal funds from the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

For Whiting, a key takeaway from the Piney Point experience is that tears will occur in the linings used at such facilities, and thus tears should be planned for. “If you have a facility with a liner, you should have a plan to locate where the tear is and be able to seal it with emergency supplies,” he advises. “This should be part of a thorough, efficient, and up-to-date emergency action plan for dam safety.”