By T.R. Witcher

The U.S. Army Garrison Mannheim was established in the German city of Mannheim in 1945, in the aftermath of World War II. The city’s center had been destroyed by Allied bombing, and as Mannheim rebuilt itself, the American Army barracks became a Cold War mainstay, growing to include several facilities and eventually hosting more than 15,000 service members and their families.

According to Stars and Stripes, a daily newspaper for the American military, gradual drawdowns of U.S. personnel in the post-Cold War era eventually led to the base’s closure in 2011. Many of the barracks’ buildings have since been demolished. But in 2015, Mannheim city officials held a master plan competition, which kick-started an effort to transform the empty 100-plus-acre site.

The result is a creative redevelopment scheme called Franklin Mitte, overseen by RVI GmbH.

The central design feature of the new project is four large residential towers, positioned throughout the barracks’ remaining buildings and surrounded by plazas. Instead of the typical generic boxes such a plan might suggest, each tower is vividly colorful and dramatically shaped like a letter — together the four buildings spell the word HOME.

Dutch architecture firm MVRDV’s entry for the master plan competition came in second, but many of its ideas found their way to the final project, including a pedestrian “Europa Axis,” which cuts a dramatic path through the neighborhood, and a walkable, grass-covered “Green Hill,” which contains within its volume a supermarket, clinic, and pharmacy.

MVRDV is also designing two of the high-rises — a dark-blue building that suggests a squared, pixelated version of the letter O and a pink building whose three vertical towers will be capped off by a pair of horizontal structures so that it visually resembles an M.

Meanwhile, the 13-story E building, designed by German firm AS+P, achieves its form with a predominately white structure with brown horizontal sections recessed into the facade; it features a combination of apartments on its upper sections and two-story maisonette apartments in its podium.

Finally, the H high-rise, designed by German firm Haas Cook Zemmrich, features a pair of 157 ft tall towers, set at 45-degree angles from their bases and joined in the center by a horizontal connecting structure.

The redevelopment of the barracks will lead to as many as 10,000 new residents on the site.

Identification and orientation

Christine Sohar, a senior project leader at MVRDV, says the firm wanted the site’s high-rises to be points of “identification and orientation.” The question, she says, “was how could these high-rises be defined? Do they get a specific form or a specific color? There was a search for that identifying element.”

Shaping the buildings as letters was a way to visually mark the site’s history and entice future residents — the buildings will also be visible for motorists driving past a nearby highway. The vivid colors serve the same purpose.

“There are so many white plaster buildings in Germany,” says Sohar. “The idea was: Let’s bring some fun in there.”

The O building is the first of the four to break ground; construction started in January. It may prove to be the most colorful. In addition to its blue facade, the building will be studded with colorful balconies — each unit will have one or two.

The balconies appear random in their placement on the facade of the building rather than in a pattern, and their color can be individually chosen, according to Sohar.

The balconies provide natural ventilation for the apartments, and the deep recesses of the windows in the facade reduce solar heating of the apartments’ interiors.

Units at the top of the building will feature skylights, while units that face the empty space in the middle of the O will have windows — and, in some, those windows will be located on the floor to provide views down into the void.

MVRDV has also designed a large, four-story staircase that will provide access from the ground up to a public terrace at the base of the empty center of the building. There will also be elevator access to this outdoor space along with a cafe and bistro.

At the top of the steps, Sohar says, “you land at the fourth floor of the O, you can look out over the whole development and start to see the other letters. You start to orient yourself. You can also go up the hill and get all the letters at once. This is something where you play a bit with the urban area, bringing people up, making it something a bit more public.”

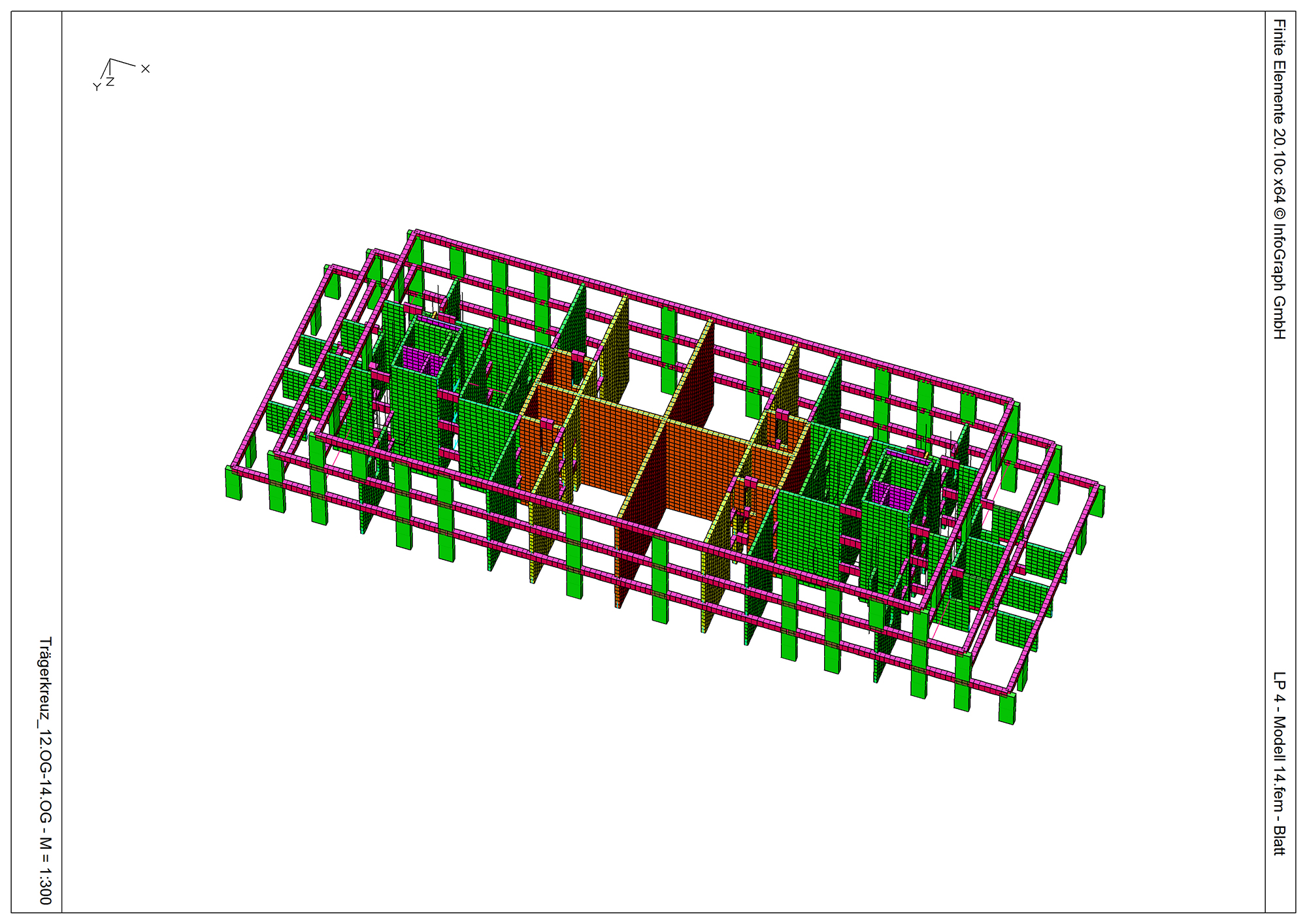

Complex engineering

The structure of the O building is really two high-rises, each stabilized by a core. The top of the O is formed by an enclosed bridgelike structure that joins the sides of these structures. The building is made of reinforced concrete slabs and reinforced concrete walls.

Darmstadt, Germany-based G+H Tragwerksplanung GmbH, a structural engineering consultancy with experience in structural design and design review of residential, office, and public service buildings, completed the structural design of the building. The firm’s work also included providing calculations for various construction states, optimizing cost and effort of scaffolding and bracing, and supporting the bridgelike structure during the building process.

Engineers also had to strengthen the building to resist seismic events. “The bridge is pretty important,” says Tobias Hartleb, Dipl.-Ing., senior project manager. “During an earthquake event those towers tend to move independently, which brings additional lateral forces to the connecting bridge part.” Two intersecting walls in the center of the bridge structure that forms the top of the O will act as a crossbeam.

At the lower corners of the building, the structure visually tapers inward like a pair of inverted staircases. Sohar says this is meant to reduce the building’s footprint. “When you are moving around this, it’s not just a thing that comes down,” she says. “You realize that there is something happening as a silhouette that is nicer than if it was coming down completely as one letter.”

To support this unusual element, engineers transferred loads from the outermost columns to inner columns with a combination of thick concrete walls and slabs containing diagonal bracing. “Thirty or 40 years ago (it) would have been very difficult to calculate loads on this unusual structure,” says Markus Hartmann, Prof. Dr.-Ing and founder of G+H.

The O building should be complete in two to three years. The M building, which is set to utilize a hybrid structure of wood and concrete, and the other buildings should break ground in the next few years.

When asked why the buildings spell home in English instead of German (“heim”), Sohar notes that many people living in Mannheim have connections to the old American base. “It was an American area; it’s not forgotten.” It was important, she says, to remember the past in order to start a new chapter. “It has certain roots in order to grow in new ways.”