By Jay Landers

Of the many business sectors affected by the COVID lockdowns, commercial office buildings have been hit particularly hard, largely as a result of the shift by many employees to working from home. In the wake of higher-than-normal vacancy rates for such properties, building owners and developers increasingly are evaluating the possibility of converting office buildings to residential use.

As illustrated by examples from San Francisco and New York City, such conversions can make sense under certain circumstances, but the spatial, logistical, and economic hurdles to be overcome are considerable.

San Francisco’s high vacancy rates

In terms of economic activity, downtown San Francisco “has not rebounded as quickly as other cities,” says Charles Bloszies, FAIA, S.E., LEED AP, a principal at the Office of Charles F. Bloszies FAIA, which specializes in refurbishing or repurposing existing urban buildings, primarily in the San Francisco area. “One theory (for this) is that we were so heavily invested in technology, and the buildings were full of tech companies,” Bloszies says. “With the pandemic, you could still have your pretty good salary as a tech worker and either stay at home or move to someplace where the cost of living was less.”

As a result, many tech companies “have vacated real estate” in downtown San Francisco, Bloszies notes. “That leaves a very, very high vacancy rate.” Hit especially hard have been class B and C office buildings, as tenants have been drawn to Class A buildings as their rents have decreased, he says.

Whereas Class A comprises the premium, highest-quality, and most desirable buildings in a market, Class B consists of typically older, but still decent, properties that cost less and have fewer amenities than Class A. Meanwhile, Class C, the lowest category, comprises older buildings that often are in poor condition or undesirable locations.

Against the backdrop of these higher vacancy rates, property owners and developers in San Francisco are asking the question, “How do we get more life into the buildings that have space available?” Bloszies says. “Residential (use) is certainly an option.”

Bloszies, whose office recently conducted a study of the feasibility of converting office space to residential use in San Francisco, notes that locations along the fringes of downtown and near public transit are ideal locations for such conversions.

“We're thinking that it's more the smaller buildings, the ones with a little bit more architectural charm, that would be more likely candidates,” Bloszies says.

New York’s underutilized buildings

In New York, the trend of converting commercial buildings to residential predates the COVID crisis, says John Cetra, FAIA, a founding principal of the New York-based architecture firm CetraRuddy. Before the pandemic, such conversions typically involved underutilized smaller buildings that had been constructed between the mid-1860s and the 1930s and could be transformed into loft apartments, Cetra says.

After COVID struck and demand dropped for office space in the city, “there were many, many more buildings that were experiencing an underutilization,” Cetra says, a situation that persists. Although some workers have returned to office buildings in the city, the rise in hybrid work schedules — wherein employees work some days at home and some days in the office — has partly offset this development, Cetra notes.

Increasingly, larger postwar buildings that were constructed between the 1950s and 1980s are among the underutilized structures in New York, Cetra says. “Those are the ones that we have been seeing a lot more recently,” he says.

Amid these trends, building owners in New York are trying to determine whether it makes sense to repurpose their underutilized office buildings, Cetra says. “What's been going on is causing the real estate development market to look at their properties to see which ones are most appropriate and can be converted” from commercial to residential, he says.

Critical factors

With office vacancies at high levels and demand for residential space strong, converting offices to residences might seem like a simple decision. However, myriad complications make the process anything but straightforward. “It's harder than you think to do these conversions,” Bloszies says.

Ideal candidates for conversion from office to residential use are older Class B buildings that have certain configurations that facilitate the use of natural lighting, a key code requirement for residential structures, Bloszies says. In particular, buildings should have “two or three street frontages” so that “you can get light in all around, or at least on three sides,” he notes.

At the same time, a structure’s floor plate is the other critical factor in determining whether an office building can be converted to residential use, Bloszies says. The deeper the floor plate, the harder it is to introduce natural lighting throughout a structure. “Not every office building is a perfect candidate because if you can't get light into bedrooms, you can't really lay it out properly,” he says. Although light wells and similar features may be used for this purpose, he says, “that adds cost and complexity to the project.”

Cetra agrees on the importance of a building’s floor plate. “That's really the No. 1 challenge,” he says. “If we can make the floor plan work first, then we have a project that we can go to the next step and look at mechanical systems and building envelope and work through all of the other aspects that will make the building viable for conversion.”

Extensive upgrades required

Converting older office buildings to residential use typically requires significant updates to ensure compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. In certain situations, and in San Francisco for sure, seismic upgrades also are required as part of such conversions. “That is also a big cost,” Bloszies says.

In New York City, relatively recent requirements pertaining to flood protection also can affect building use, particularly on lower levels, Cetra says. In some cases, for example, residential use is prohibited below a certain design flood elevation, and mechanical and electrical systems either must be waterproofed or relocated to a certain height.

As for the larger postwar office buildings in New York City that some owners are considering converting to residential use, those structures pose certain challenges beyond their large floor plates, Cetra says. “They had very extensive elevatoring systems because there were a lot of people coming in and out of the buildings at very specific times of the day,” he says. “So, they had to handle large volumes of traffic, which is in contrast to a residential building.” In some cases, it makes sense to remove those elevators that are no longer needed.

Because they often were hermetically sealed, the same buildings also may present complications related to their ventilation and facades. “There were no operable windows,” Cetra says. Therefore, a conversion would require the addition of such windows. Such an upgrade “can be a pretty costly issue, but it's just something that has to be done,” he says. Meanwhile, older facades “may also have to be upgraded to comply with current energy code requirements,” Cetra notes. “That means changing the glass to some extent.”

Finally, the larger postwar office buildings “were built in the period of very cheap energy costs,” Cetra says. As a result, their heating and cooling systems typically consist of large cooling towers and air-handling units at the top of the building. Such systems transfer conditioned air by means of ductwork that distributes the air along the building’s perimeter. “That was a fine system for the time but clearly not a very efficient system for a residential building,” where residents require individual control of air temperatures, Cetra says. “The entire mechanical plant then will have to be upgraded.”

Because of these and similar requirements, converting office space to residential use typically requires a complete overhaul of a structure’s interior. “The kinds of buildings that tend to be perfect candidates are ones that you're pretty much gutting and redoing,” Bloszies says. “Usually we can save the elevator core and the stairs, but that's about it.”

Overcoming the complications

Despite the many complications, converting office space to residential units does at times make sense, particularly when building vacancies are at such high levels, Bloszies says. “All of a sudden, you have an opportunity, of sorts, to do these projects because you don't have to buy out leases and things like that,” he says.

In some cases, adding more floors to a structure can help offset the upgrade costs by providing more rentable or salable square footage, Bloszies says. “You can amortize that cost with less expensive construction as you go up, within limits.”

As an example, Bloszies points to a project his firm worked on more than a decade ago in downtown San Francisco. The city’s first skyscraper — the Old Chronicle Building, at 690 Market Street and dating to 1889 — was converted into luxury residences. As part of the conversion, eight stories were added to the structure, a portion of which was layered back. “It was a big old building that had to be hollowed out completely,” Bloszies says. “It was essentially a new building with a historic jacket and a modern piece above it.”

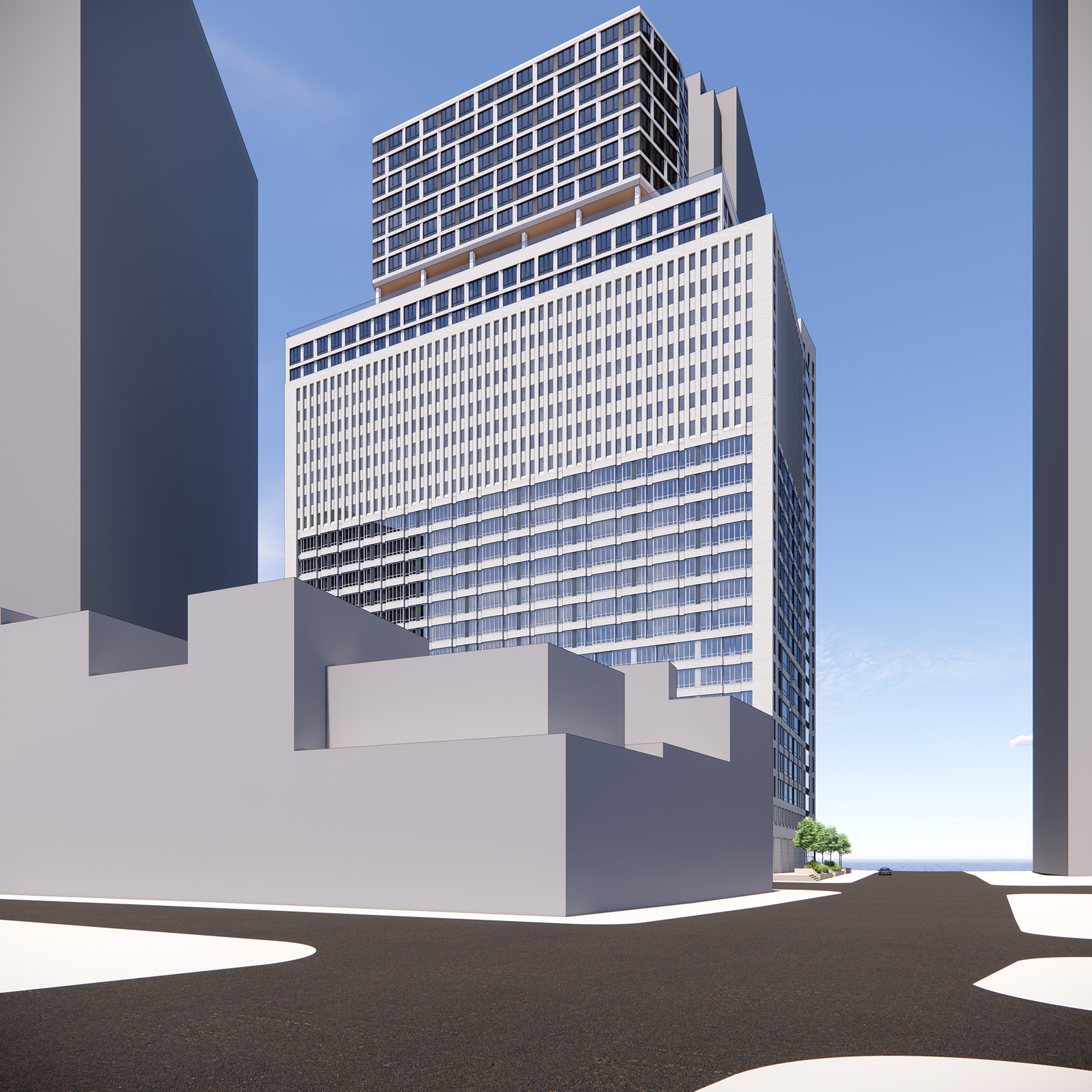

On a more contemporary note, Cetra’s office is working on what he says is the “largest conversion of commercial to residential in the country.” Located in the financial district of lower Manhattan, 25 Water Street originally was constructed as an office building in 1968. Notable for its “very few windows and large floor plates,” according to Cetra, the 22-story building presented some clear obstacles to a conversion to residential use.

“We're doing a number of modifications to that building to make it work for residential use,” Cetra says. Chief among them is a plan to “carve out” the center of the building to create courtyards that enable light and air to access the interior portions of the building, he says. To make up for the lost floor space, 10 stories will be added to the top of the building, which will receive structural bracing to accommodate the increased wind loads. “For our client, there's no loss in the gross floor area,” Cetra says. Construction on the project, which will result in approximately 1,300 residential units, is expected to begin this year.

This article first appeared in Civil Engineering Online.