The internet ecosystem is constantly evolving, and while it has enabled businesses to grow in ways never thought possible, it has also created a number of unintended opportunities for cyberthieves to take advantage of unsuspecting engineers and their businesses. Knowing what to do should you fall victim to a cyberthief can protect you and your business from serious problems.

Picture this. You have devoted years to developing proprietary drawings and close relationships with clients. These clients are the backbone of your business. Unfortunately, you wake up one morning and realize that your website and email have been disabled. Your urgent investigation reveals that your internet domain name has been hijacked, and a cyberthief now has the keys to the kingdom — access to your intellectual property and confidential client communications. Now the cyberthief is either holding your data hostage unless a ransom is paid, manipulating your website and email system while misappropriating your proprietary information and source code, or displaying vulgar imagery on your website for his or her own personal gain at the expense of your business reputation.

This scenario may sound like a fictional cyber thriller, but too often it becomes a reality for small and large business owners, including engineering firms.

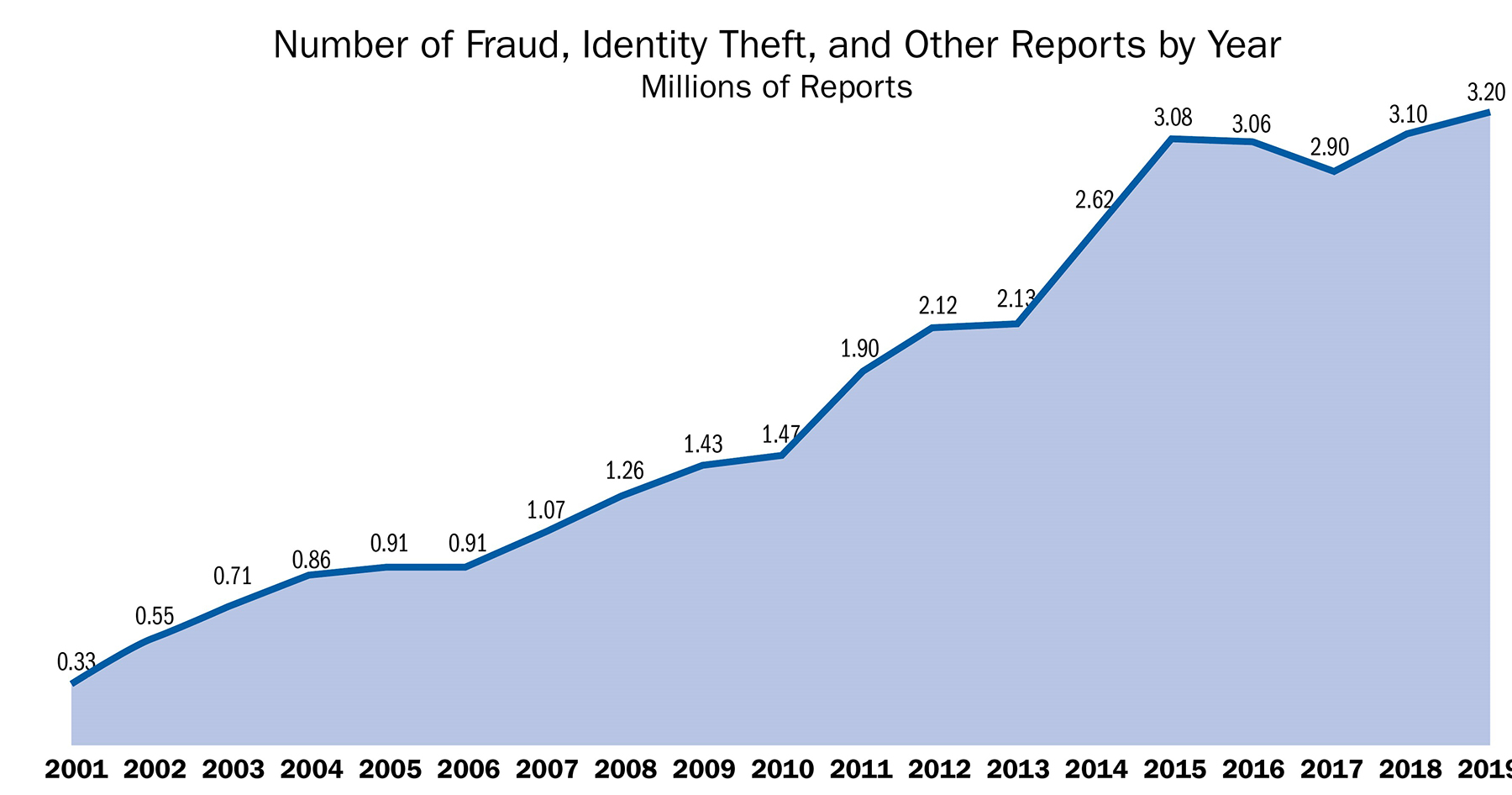

Unlawful exploitation of American intellectual property has become a serious threat to U.S. national interests, and internet-enabled crimes and scams relentlessly invade our personal and professional lives. The 2019 Internet Crime Report, released by the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, states that the FBI received “467,361 complaints in 2019 — an average of nearly 1,300 every day.” And according to the Annual Intellectual Property Report to Congress, published in February 2019, it is estimated that theft of intellectual property, including theft of trade secrets and counterfeit goods, directly costs the U.S. economy up to $600 billion annually. The increase in sheer volume of intellectual property theft has been coupled with an evolution in the sophistication of scams through the use of multiple threat vectors via the internet.

For example, recent studies have shown that new top-level domains issued — the suffix of a domain name (such as .xyz) — are being used for scams at 10 times the rate of legacy TLDs such as .com, .net, and .org, as reported in Statistical Analysis of DNS Abuse in gTLDs Final Report. Well-known consumer brands are frequently co-opted to perpetuate internet-based fraud, and scammers do not discriminate. Just as the internet has enabled businesses to substantially expand their reach, it has done the same for cyberthieves. In 2019, nearly one-in-three breaches involved a small business, according to Verizon’s 2020 Data Breach Investigations Report.

In another instance, scammers sent threatening emails and text messages seemingly from the U.S. Department of Transportation to small businesses. The communications directed the recipients to websites operated by scammers who then directed the victims to pay expensive fees “required” by the government (Federal Trade Commission v. Dotauthority.com, 2016).

Millions of Americans rely on the services of the engineering profession for critical aspects of their everyday lives, making the potential exposure and risks to engineering firms particularly acute. Given these staggering numbers, it is not a question of if it will happen to you but when.

While not fully reported in the press, the effects of internet-based intellectual property theft or consumer fraud can be wide reaching and devastating to a company. Victims of these types of internet crimes can experience lapses in supplying critical services, destruction of goodwill and reputation, consumer confusion, and significant monetary loss. Author Robert Johnson III gets directly to the point in his January 2019 article in Cybercrime Magazine titled “60 Percent of Small Companies Close within 6 Months of Being Hacked.”

Beyond these immediate and tangible harms, failure to take action can undermine ownership rights and in some cases result in the waiver of certain rights, especially with respect to copyrighted material and trademarks that are often misused by thieves as part of these scams.

So, what exactly are these harms, and what can you do to make sure you are best positioned if you are the target of a cybercriminal?

Cybersquatting

There are several risks engineering firms face that are broadly categorized as cybersquatting. The World Intellectual Property Organization generally defines cybersquatting as the bad-faith registration or use of a domain name targeting a trademark. Typically, a cybersquatter buys or steals an internet domain name that is similar or identical to the trademark or trade name of a business and uses it for some nefarious purpose.

Cybersquatting has long been a problem for businesses and brands. Some of the more famous disputes involve a cybersquatter attempting to sell jethrotull.com to the band Jethro Tull for more than $10,000 and cybersquatters registering a variety of versions of the domain name ebay.com to scam consumers. In 1999, Congress attempted to address this problem by passing the landmark Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (known as the ACPA), which created specific legal remedies for intellectual property owners to pursue against cybersquatters. This law has helped address the problem by providing solid legal grounds by which to address internet scams, but recent developments have given new fodder to enterprising cyberthieves.

t photo credit]

t photo credit] As of June, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the organization that loosely regulates internet domain names, reported there were more than 1,500 TLDs in use (.com, .global, .online, etc.). That means that now, even if you own engineering.com, a cybersquatter could register engineering.global or engineering.online and design a website to look exactly like your engineering.com site. Furthermore, the European Union passed the General Data Protection Regulation — a set of sweeping data privacy regulations implemented in 2018 — that has exponentially (and unintentionally) increased the ability of cybersquatters to operate with virtual anonymity. If registrants of infringing domains can more easily remain anonymous, victims must become savvier in their approaches to combating the unlawful behavior.

Within the general category of cybersquatting, there are several subcategories that we have encountered in our practice with increasing frequency: misuse of domain names, known as typosquatting; business email compromise scams; and domain name theft.

Typosquatting involves registering a domain name that includes a typo of a legitimate site. The site is then typically used to display advertisements related to the legitimate site, to distribute computer viruses or malware, or to collect visitors’ personal information for inappropriate or illegal uses. For example, a typosquatter would buy the domain name facebok.com and create a similar looking website to facebook.com that prompts visitors to enter their login information or download harmful malware.

This gives the cybersquatter access to that user’s account as well as other accounts using the same password, or infects the user’s computer. At our law firm, for example, one of our financial-services clients was a target of cybersquatters who had registered more than 700 variations of the client’s brand name, all representing different typographical errors. Each domain contained a small typo, and each website was configured to display ads, services, and even computer viruses related to the client’s legitimate business. With the expansion of available TLDs, the exposure of businesses of all sizes to this type of scam is growing.

Business email compromise scams are a subset of typosquatting, and they often occur following some type of security breach. In 2019, these types of crimes outnumbered the next most used type by more than 50,000, costing victims more than $50 million, according to the Internet Crime Complaint Center’s 2019 report. In a Feb. 20, 2018, press release, the Federal Trade Commission reported that 11 web-hosting services that market themselves to small businesses did not provide certain default security measures like email authentication, which has left small firms in particular at risk of facilitating phishing scams. Even with these protections, a cyberthief can use typosquatted domains to send out authentic looking emails to employees at a company or to a business’s customers seeking sensitive information or directing individuals to pay fraudulent invoices.

Recently, another client was targeted by this type of email scam. A cybersquatter registered a confusingly similar domain name and then used it to send emails with fake invoices to customers of our client. When first reading the email, the address looked exactly like one of our client’s legitimate email addresses, and it easily fooled one unsuspecting customer. Luckily, the issue was discovered shortly before the customer wired the cyberthief $25,000. Even more frightening, according to publicly available records, the same registrant owned more than 200 domains consisting of typos of business names and seemingly for use in similar scams.

Domain name theft can range from cyberthieves’ monitoring and registering domains that have unintentionally lapsed to obtaining unauthorized access and transferring ownership of a domain, which provides them with access to all company emails or potentially valuable source code and proprietary databases. In one such case, a cyberthief gained unauthorized access to a domain name account and transferred the ownership of the domain name; the thief also obtained a copy of the source code, databases, and graphical interfaces for the website — six years of the victim’s work (Almeida v. Tabelafipebrasil.com, 2019).

In another instance, a thief gained access to an engineering firm’s domain name account and transferred the domain name away from the legitimate owner, thereby disabling the firm’s website and email. As we will describe later in this article, in each instance we moved quickly to pursue relief, shut down the cyberthief’s misuse of client assets, and return control to the client.

Other threats

Engineers face additional threats to their intellectual property via the internet. These include scams that use copyrighted material and trademarks on websites, blogs, or social media posts to falsely associate a brand with a website or products but that are technically not considered cybersquatting. For a claim to qualify as cybersquatting, an infringer must make use of a protected trademark in a domain name. Thus, social media posts and blogs generally do not qualify, and websites infringing on a trademark without using the mark in a domain name are also excluded from the scope of the ACPA. For example, if a scammer created a website called recentnews.xyz and configured that website to look exactly like Facebook, the fact that “Facebook” or a domain name confusingly similar to “Facebook” was not being used in the domain name itself would mean there could not be a cybersquatting claim. The victim company would need to pursue separate legal claims.

Recently, our firm had another client (a large news organization) that discovered that more than 30 domain names were being used to operate a large network of fraudulent websites (Fox News Network LLC v. xofnews.com, 2020). When accessing these websites, users saw a site designed to look identical to our client’s branded website, prominently displaying a counterfeit trademark, with fraudulent news articles about a so-called miracle dietary supplement that would help people lose weight. Registrants of the infringing websites had concealed their identities to avoid liability.

Businesses also face threats in the form of robocall and email scams. Like buying an infringing domain name, these scams are cheap and easy ways to disrupt your business and if not corrected, can cause irreparable harm. Over the last five years, this type of fraud has dramatically increased in number and complexity.

For example, scammers, purporting to be from Google Ads and soliciting login information or other sensitive data, have targeted small businesses via emails and robocalls. The COVID-19 pandemic has only made matters worse, and since March there have been myriad scams ranging from emails disguised as health advice from the World Health Organization; emails from employers about new telecommuting policies; and even emails, websites, and robocalls about purported COVID cures.

Solutions

While these threats sound overwhelming, staying alert and remaining nimble to take the right steps put you in a better position to appropriately respond if these problems do occur. First, and often overlooked, is establishing ownership over your company’s trademarks and copyright-protected works in advance. While seemingly simple, this can become a complicated issue in certain instances.

Second, many businesses use brand abuse monitoring tools. Brand abuse tools allow businesses to identify unauthorized brand uses but in many cases do not provide solutions.

Third, businesses have in the past defensively registered multiple domain names to prevent registration by scam artists, but this is no longer as practical with more than 1,400 new domain registries offering an unlimited number of variations on company names and brands. Businesses should still register the obvious domain variations as a defensive measure, but this alone is unlikely to be sufficient to protect against online scams.

Fourth, businesses should develop effective action protocols ahead of time. Every business can institute preventive security measures in an effort to thwart issues and mitigate their harm when they do arise.

Finally, in the event a business does become a target of a cyberthief, recognize that there are some specific legal solutions available to protect your rights.

Taking action without litigation

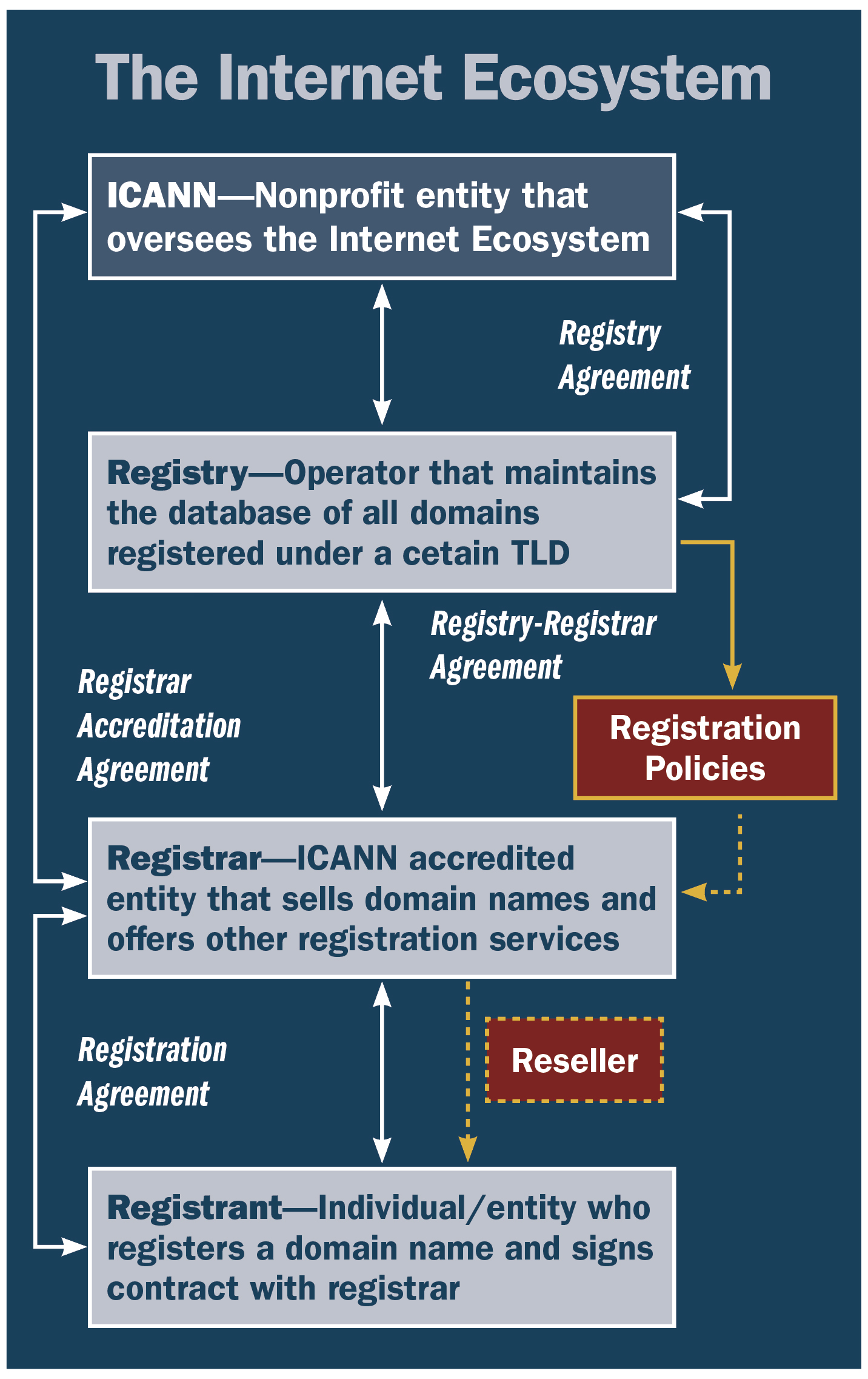

If you become aware that someone is infringing on your intellectual property via an internet domain name, the first step should be to attempt to identify the registrant/operator of the domain. When an entity registers a domain name, it must provide identifying contact information to the registrar (the entity that sells and registers the domain). This information was for many years available in a publicly accessible database known as the Whois.

As discussed, due to the new General Data Protection Regulation, this information is often inaccurate, incomplete, or totally concealed by domain name registrars or third-party privacy services. Even if accurate registrant data is found, cyberthieves may not be responsive (unless they are anonymously seeking a ransom) or reasonable. Thus, a business should attempt to identify the host, the registrar, and/or the registry — where the domain is located physically — using publicly available information and the ICANN Domain Name Registration Data Lookup. Then, the business should send a formal abuse report, takedown request, or notice to these entities. These requests are quick and sometimes effective, and they can serve as evidence of noncompliance if ignored. Although service providers have been more responsive recently due to COVID-related scams, many such requests are ignored by less reputable service providers.

If a takedown request is not effective, you can protect your rights through dispute resolution or formal litigation. As to the former, there are two main dispute resolution services that deal with domain name disputes — the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute Resolution Policy and the Uniform Rapid Suspension System. Both are designed to offer low-cost dispute resolution forums for cybersquatting cases. The UDRP is the more used of the two, and it offers broader relief. Under the UDRP process, a claimant can ultimately recover a domain name, but this process is slower and has higher filing fees.

Alternatively, URS was designed to complement the UDRP system and offers a lower-cost and faster path to relief in the most clear-cut cases of infringement. Note, however, that a claimant in a URS proceeding is entitled only to limited relief — suspension of a domain — and there is a higher burden of proof. Additionally, these systems are limited purely to cybersquatting disputes. If a cyberthief is not using a domain name similar to your trademark, these services are not available, and you will need a court order to disable the scam.

Taking action with litigation

Depending on the type of infringing activity, there are two primary types of lawsuits available to parties. The first is an in rem action, and the second is a John Doe action. These are not mutually exclusive, and a lawsuit can often be a combination of both. Whether a claim is brought as an in remor John Doe claim can, however, determine what relief is available.

In rem jurisdiction is a lesser-known legal concept in which an action is brought against property as opposed to a person — the court in which the property is located has jurisdiction over that property. This is particularly useful in the case of an elusive or unknown defendant. Common examples of these types of actions involve disputes over ownership of a piece of property (a boat or found treasure) or asset forfeiture cases by the U.S. government. Congress, however, expanded this type of jurisdiction to include domain names when it passed the ACPA.

To put it plainly, domain names are considered physical property, and an action may be brought where the domain name registry is located. For example, any domain name ending in .com, .net, or .org is deemed to be located in Northern Virginia, and any ACPA claim against a website ending in one of these TLDs can be brought in the federal court in Alexandria, Virginia.

In rem actions offer several advantages. First, they do not require an actual person or entity to appear as a defendant in the lawsuit (locating cybersquatters can be particularly difficult), and you can proceed to recover the domain name. Second, the Virginia federal court that can hear these cases is known as the “rocket docket” because it is one of the fastest dockets in the country. Our firm has been able to obtain relief in these cases in as fast as three months. Third, these actions are more cost-effective than bulk domain-name UDRP actions when a business needs to recover multiple domains. Similar to UDRP and URS, these actions are limited to cybersquatting. Furthermore, there must be a connection between all domains at issue.

In instances in which the infringement or scam does not qualify as cybersquatting, however, you also have the option of bringing a John Doe action. This action can be used to discover the identity of an unknown infringer, and a successful action can provide a nationally enforceable court order against any domestic entity involved in servicingthe infringing website. This means a rights holder can still disable the website if the operator is overseas, which it often is, and/or is not identifiable. Furthermore, these broad injunctions can be enforceable against future websites.

For example, a client of ours, a professional organization, pursued such action against two websites operated by multiple John Does (American Chemical Society v. Does, 2017). The defendants stole the organization’s copyright-protected scientific articles and reproduced them on the internet without permission. As part of the broad injunction granted by the court, we were able to shut down the infringing websites as well as similar websites that subsequently appeared. Additionally, we were able to secure a $4.8 million judgment for trademark counterfeiting and copyright infringement on behalf of our client.

Regardless of what type of action suits a particular circumstance, pursuing litigation often offers the most effective relief for protecting a business’s intellectual property rights. As you might expect, an injunction issued by a federal court is a powerful tool and can be used nationwide. We have also had success in getting U.S. court decisions enforced in other countries. Judgments can be directed to domain name registries, hosts, email providers, and other entities helping the cyberthief (e.g., payment services), and they can be drafted in broad enough language that they may be invoked to address future related infringements.

Additionally, in cases in which a business can identify the real identity of the John Doe, there is also the potential for a monetary award or asset seizure. Even in the context of a less sinister dispute, like a general business dispute over domain ownership, the court can provide a title declaration and bring finality to the issue.

On the robocall front, the solutions are similar. You can send cease-and-desist letters to domestic originators or gateway providers — the entities that provide phone services — and can pursue litigation similar to internet-scam litigation to get a broad injunction against the source of the calls. Additionally, you can submit enforcement referrals to the Department of Justice, the Federal Communications Commission, or the Federal Trade Commission.

Solutions to robocall scams have also become the subject of private companies. Currently, there is a “trace-back group” — a collaborative industry effort made up of the major players, including companies like Verizon and Comcast — that actively works to trace back and identify the source of robocalls. Such information can then be used, if necessary, in an action to pursue relief against the bad actors, hopefully bringing peace and stability back to your business before it is too late.

The internet ecosystem is constantly evolving, and while it has enabled businesses to grow in ways never thought possible, it has also created a number of unintended opportunities for cyberthieves to take advantage of unsuspecting engineers and their businesses. At times, the number and types of scams can seem overwhelming, especially to smaller businesses with limited resources. Nonetheless, having a basic understanding of the proactive and reactive steps that can be taken when these problems arise, regardless of the size or type of business, can protect you from serious problems when a savvy cyberthief attacks.

You have rights, and you should consider the best way to protect your hard work, your intellectual property, and your valuable client relationships.

Attison L. Barnes III is a cofounder of Wiley Rein LLP in Washington, D.C. David E. Weslow and Spencer C. Brooks are a partner and an associate, respectively, in the firm.

This article first appeared in the December 2020 issue of Civil Engineering as "Beating Cyberthieves."