By Alexa Mitchell, P.E., Jennifer Steen, P.E., PMP, ENV SP, and Will Sharp, P.E., PTOE

The ongoing shift toward digital delivery will have profound implications for transportation agencies and engineering companies

For years, building information modeling and 3D-engineered models have been available to provide extra information and visualization assistance on road and bridge projects. But printed 2D plans have largely remained the contractual deliverable for construction.

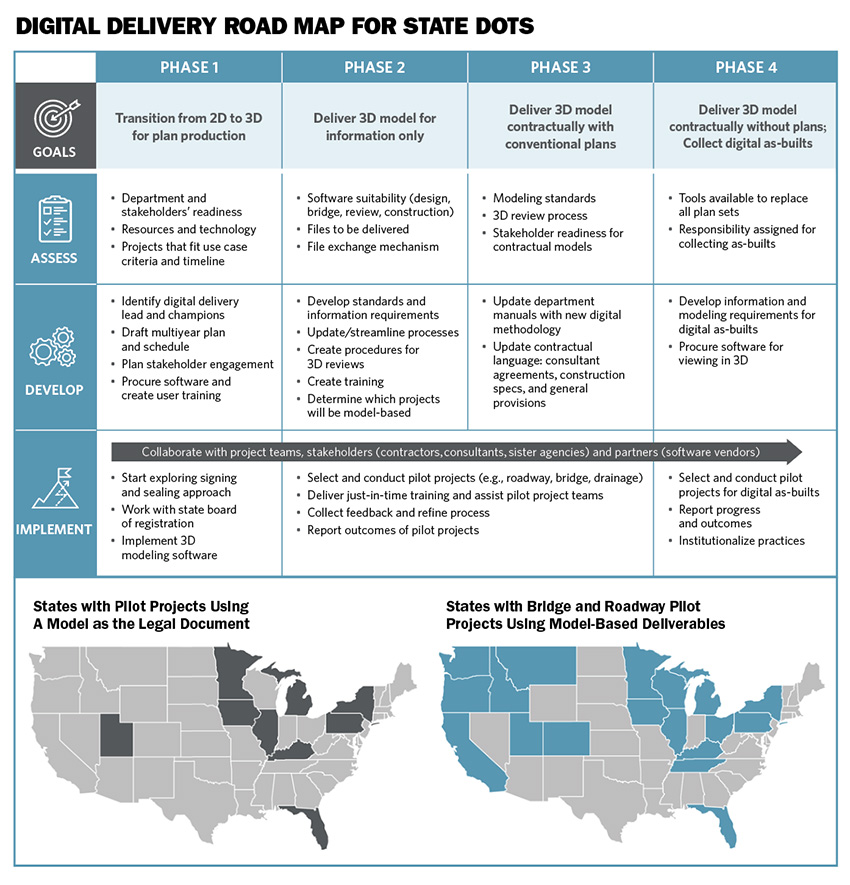

Now, though, many states and agencies across the U.S. are beginning to explore a model-based delivery approach, steadily leaving 2D plans behind in favor of an all-digital delivery.

HDR, a global engineering, architecture, environmental, and construction services firm, works with state departments of transportation across the country, and a growing number of agencies have either begun requiring model-based deliverables or plan to within the next five years. Many of these entities are working on pilot projects that move them toward a model-based delivery future.

And national organizations, such as the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, the Transportation Research Board, and the National Institute of Building Sciences are dedicating significant resources to developing best practices and national standards.

Research confirms benefits

BIM for infrastructure is gaining popularity because of an array of benefits: improved constructability, fewer change orders, enhanced visualization, better interdisciplinary coordination, an improved ability to share design intent, and enhanced design and construction efficiency. In plain terms, the approach means lower project costs and saved time.

As these digital models are used more throughout construction, they also hold the promise of better asset management, creating digital as-builts that provide future engineers confidence that the plans they see are what was constructed. Importantly, BIM and geographic information systems are also moving steadily closer to integration, with communication between software and file types improving each year.

HDR recently completed benefit-cost analysis research for TRB and the Federal Highway Administration that validates the benefits of model-based delivery, showing that it makes financial sense for transportation agencies to make this change. After 18 months of analysis, the research team identified 29 benefits of BIM and 13 costs, with the biggest benefit being a reduction in change orders.

After reviewing projects that used BIM and digital delivery, researchers found that its use saved about 15% in change orders — a significant financial benefit. The overall conclusion was clear: A shift to digital delivery pays for itself within a few years.

Pennsylvania leadership in 3D

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation is on the leading edge of this transition with a five-year program called the Digital Delivery Directive 2025 plan. By the end of the initiative in 2025, PennDOT expects to have the ability for all its projects to be bid and constructed using 3D technology. HDR is leading the planning and implementation of the initiative, including developing modeling requirements, processes, and guidance on contract language.

The PennDOT effort includes the development of new statewide standards and workflows, extensive training, and the completion of multiple pilot projects to test and refine the department’s processes.

Since the project’s start in late 2020, PennDOT has made considerable progress toward its goal. An internal review mapped existing processes, and procurement language is being reviewed and adjusted as needed to reflect new scopes of work for design. Modeling requirements are being set, creating design standards for state projects. The department has also begun extensive and ongoing stakeholder engagement across the many disciplines and industries these changes will affect.

Phased pilot approach

Pilot projects in Pennsylvania are testing new approaches in gathering data for digital as-builts and delivering project information to contractors. These pilots are being rolled out incrementally, with each building on the previous project. The process began with a single project PDF, which is a piloted transition from sheeted paper plans to a digital roll plot along with cross section sheets.

This interim step is meant to make people feel comfortable with not using traditional sheets, instead reviewing projects using 2D views similar to what will appear in a 3D model but using a familiar PDF format.

Building upon the PDF pilots, roadway authoring pilots (Existing Ground Confidence Level/Roadway Authoring) will test how teams function without cross section sheets. To improve success, new tools will be provided to access 3D models using familiar views such as plan, profile, and cross section but directly from the models without any sheets.

Scheduled to begin this year, bridge authoring pilots will build on the previous two, and finally, a series of drainage authoring projects this year and the next will pilot the production of projects with all disciplines modeling in 3D.

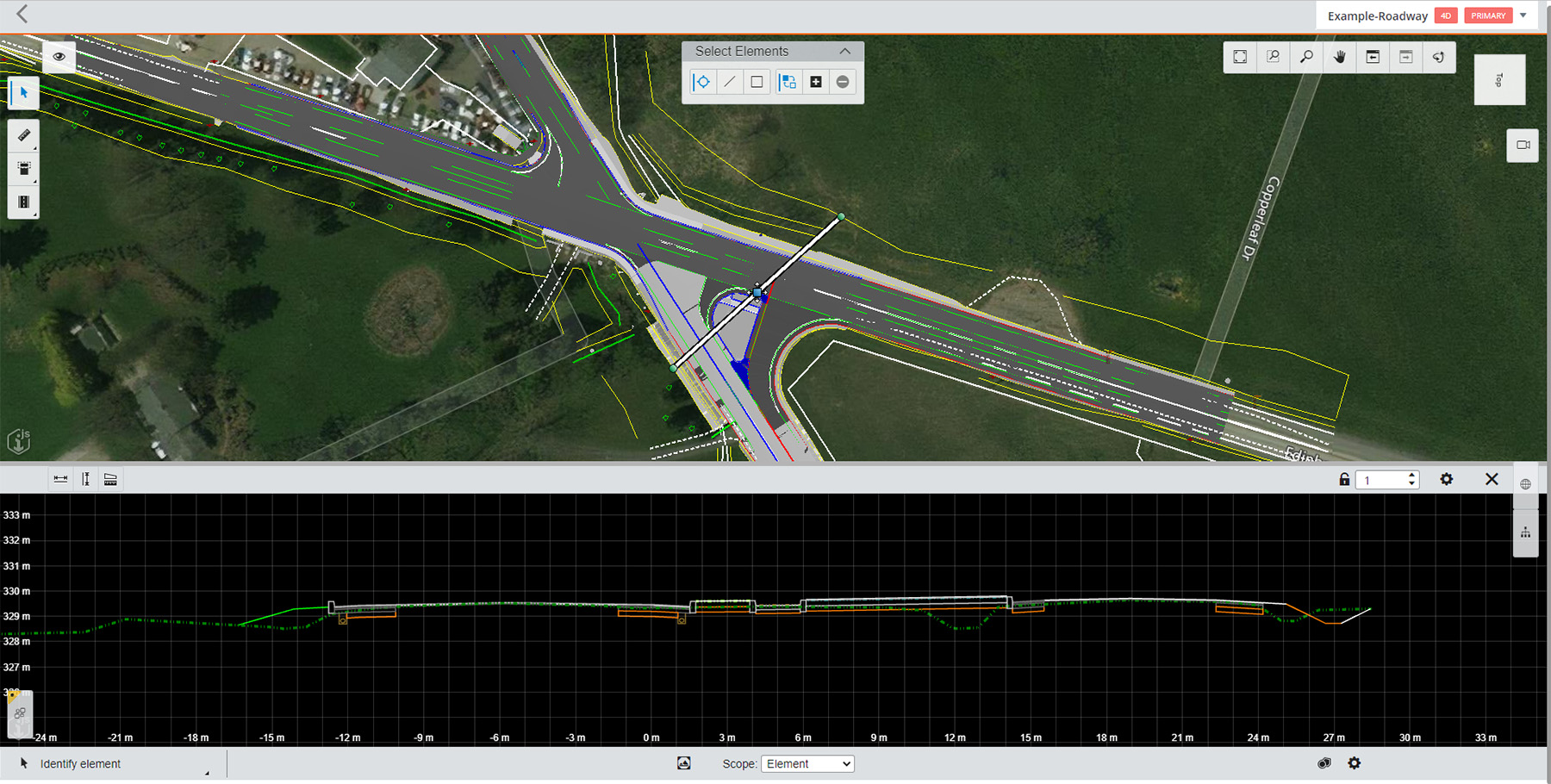

In late 2022, PennDOT held its first model-based review of 3D models developed as part of the EGCL/Roadway Authoring pilot projects. This significant step marks the first time an internal PennDOT design team has reviewed a project using 3D models instead of cross sections.

The agency is using a cloud-based solution — Bentley Systems’ ProjectWise Design Review — to review the project model in real time while documenting and assigning comments. The software keeps track of who makes a comment and connects the comment to the location of the issue in the model, with the option of assigning the comment to a specific designer. This step expedites the review process from days to hours.

Early PennDOT successes offer lessons

More than half of PennDOT’s Digital Delivery Directive 2025 initiative remains, but the project offers an excellent example of a comprehensive implementation with some early lessons for other states:

Develop and empower champions. A far-reaching shift such as this requires the input and acceptance of stakeholders throughout an agency and beyond. There are many approaches to digital delivery, and champions with clear visions who are fully behind the plans are key to moving efforts forward and not getting stuck.

The best advocates are familiar with agency operations down to the local level and lead digital delivery solutions with a keen understanding of how these changes will affect staff and projects. Influencers looked up to by others, whether they have titles or not, can make or break an initiative.

Fully understand the current process. Some roles and needs will change in Pennsylvania. Having a clear grasp of how projects already move through the planning, design, and construction processes has helped identify potential efficiencies and revealed what training will be needed and where.

Let people kick the tires. New software, methods, and requirements cause a lot of uncertainty. To reduce this, PennDOT created a simulated 3D bid document environment, with sample data from a project that has been built. This “sandbox” allows contractors to load and view files and practice navigating this new environment as much as needed. Access is provided to contractors ahead of bidding on pilot projects, and a version is also being created for inspectors.

Advancing toward BIM model as legal document

PennDOT is not alone in seeing the potential of this technology and starting a transition. National transportation industry efforts to begin the transition to signed and sealed 3D deliverables have involved many TRB and AASHTO committees as well as the FHWA, American Council of Engineering Companies, American Road & Transportation Builders Association, and other industry partners in the last several years.

In February 2020, ACEC surveyed member firms nationwide to identify engineering company concerns with the transition from 2D plans to the 3D model as legal document, or MALD, approach. These concerns and proposed mitigation measures were articulated by ACEC representatives to the AASHTO Committee on Design, Joint Technical Committee on Electronic Engineering Standards. Top engineering company concerns included:

- Data security of contractual deliverables.

- Clear definition of model accuracies and tolerances.

- Quality control process for 3D models.

- Lack of contractor experience with 3D model information.

- Engineering company investment for additional software and training.

HDR has assisted ACEC in working proactively with industry partners to address these concerns, including providing guidance on consistently identifying digital delivery contractual requirements with MALD.

Contractors have also been actively involved in these efforts. ARTBA, through its Innovation & Technology Forum, recently published a Digital Construction Policy Statement. ARTBA notes these new technologies will reduce risk, increase efficiency, and enable safer, higher-quality, and more environmentally sustainable projects. To accelerate innovation in design and construction, ARTBA is supportive of MALD and the adoption of open data standards for infrastructure projects.

Model-based advancements across states

In at least nine states, pilot projects have begun or been completed using MALD. While about a third of state DOTs now require a for-information-only BIM model on projects, some pilot projects have gone further, making the model the primary contractual document and in many cases eliminating selected 2D plan sheets.

HDR has assisted in the design and delivery of projects using MALD in multiple states, serving as the engineer of record for the models and overseeing their use. These high-profile projects — roadways and bridges — have served to measure the state of current technology and determine agency needs and next steps. Some key recommendations from these initial efforts include the following:

Plan for continued designer support during construction. As this technology and software emerge, the adjustment to new formats means that designers who helped craft project plans might need to assist construction teams in efficiently navigating digital delivery information.

Manage the pace of implementation. Instead of attempting to do everything at once, isolate and solve one problem at a time. It takes less time to find solutions to smaller problems, which in the long run speeds up a full transition.

Even after picking the right tools, expect updates and workarounds. Modeling software is advanced, but it is still evolving to meet the diverse needs of civil engineering projects. Programs should customize their efforts to make the best use of them. On the Interstate 80/I-380 interchange reconstruction project in Iowa, for instance, the information displayed by default in modeling software included important data as well as information that was irrelevant or duplicative. To reduce confusion and promote clarity, the Iowa DOT and HDR team used two additional programs to modify element properties and provide only the needed data.

Define the contract requirements and desired outcomes. As with any new venture, it is important to clearly define expectations to avoid assumptions by any party. Contracts should include the required level of development for each project element, the intended use of the model, data workflow and security expectations, and required file formats.

Agencywide or statewide standards will allow digital delivery adoption to move beyond a pilot. Project teams should be able to trust that elements will be designed the same way each time. This was a major point of contractor feedback in Utah, a situation for which HDR helped create the nation’s first model development standards manual that details what should and should not be included in a project model.

Agency implications require upfront planning

On the agency level, this transition requires close and ongoing collaboration with a wide spectrum of stakeholders. Contractors, utilities, railroads, engineering companies, municipalities, regulatory and sister agencies, and more will be affected by the shift from the sort of 2D plan sets they have used for decades.

Each group will need to understand new requirements to review project models and how they will contribute to these models. State DOTs cannot fully implement 3D models without utilities and railroads also providing the necessary data to make 3D models of their networks to allow for clash detection and constructability reviews.

New software and hardware will be necessary for full implementation, and agencies may have to choose between competing proprietary software providers. A fully developed digital workspace, with standardized elements and requirements, is also needed for engineers to create their models. The 3D modeling software must be configured to provide all the necessary tools for each discipline. This includes standard 3D objects that are often not included in state DOT libraries like pipes or drop inlets.

Procurement, regulation, and contract language are also changing. Procurement documents and standards need to be updated to reflect new delivery requirements. In some cases, state statutes or regulations will need to be updated to allow signed and sealed 3D models.

Agency legal counsel will be involved as contract requirements are updated with new specifics on file formats, naming conventions, model development standards, and authorized uses and limitations. With this data-centric mindset will also come a new emphasis on data security, with new protocols needed for long-term storage, access, and permissions.

Some agency personnel roles will likely change as work shifts toward model-based design. Workflows developed to produce traditional plan sheets will need to be adjusted to account for more detailed model-based design. Expectations and roles also need to be established during the transition period.

If subconsultants are not experienced with 3D design, for example, who will be responsible for converting their 2D plans to the 3D model used as the deliverable? In addition, new quality-management workflows must be established to systematically check the detailed construction-level accuracy of 3D models.

Agencies might also have to increase investments in data acquisition technologies such as lidar. For many horizontal projects, plan sets have traditionally included cross sections every 50 ft or 100 ft, with the assumption that contractors will interpret the space in between during construction.

A 3D deliverable, however, greatly reduces the amount of uncertainty between cross sections, and in many cases 3D deliverables provide the digital data needed to complete automated machine guidance paving and grading. This higher-level detail across an entire project means problems can be anticipated earlier. It also means better surveys will be needed with a higher level of accuracy.

Engineer implications require training and support

For individual engineers, the implications are also considerable, with training as the most pressing need. Many engineers are familiar with creating 3D design models. At least 16 state DOTs require a for-information-only model with projects. But these models can vary considerably in their level of detail and the embedded information. Designers, whether at state DOTs or engineering companies, will need continued education on how to produce 3D plans that can be used as primary contractual deliverables for projects.

Continuing education on evolving software will also be required as the state of the practice advances. Engineers who are experienced and comfortable with the latest in BIM and 3D modeling will be in high demand in the coming years. Much of this training is happening organically at the design team level. Some larger consultants, such as HDR, have developed in-house training programs, but industrywide certifications and formalized training opportunities have not yet become widespread.

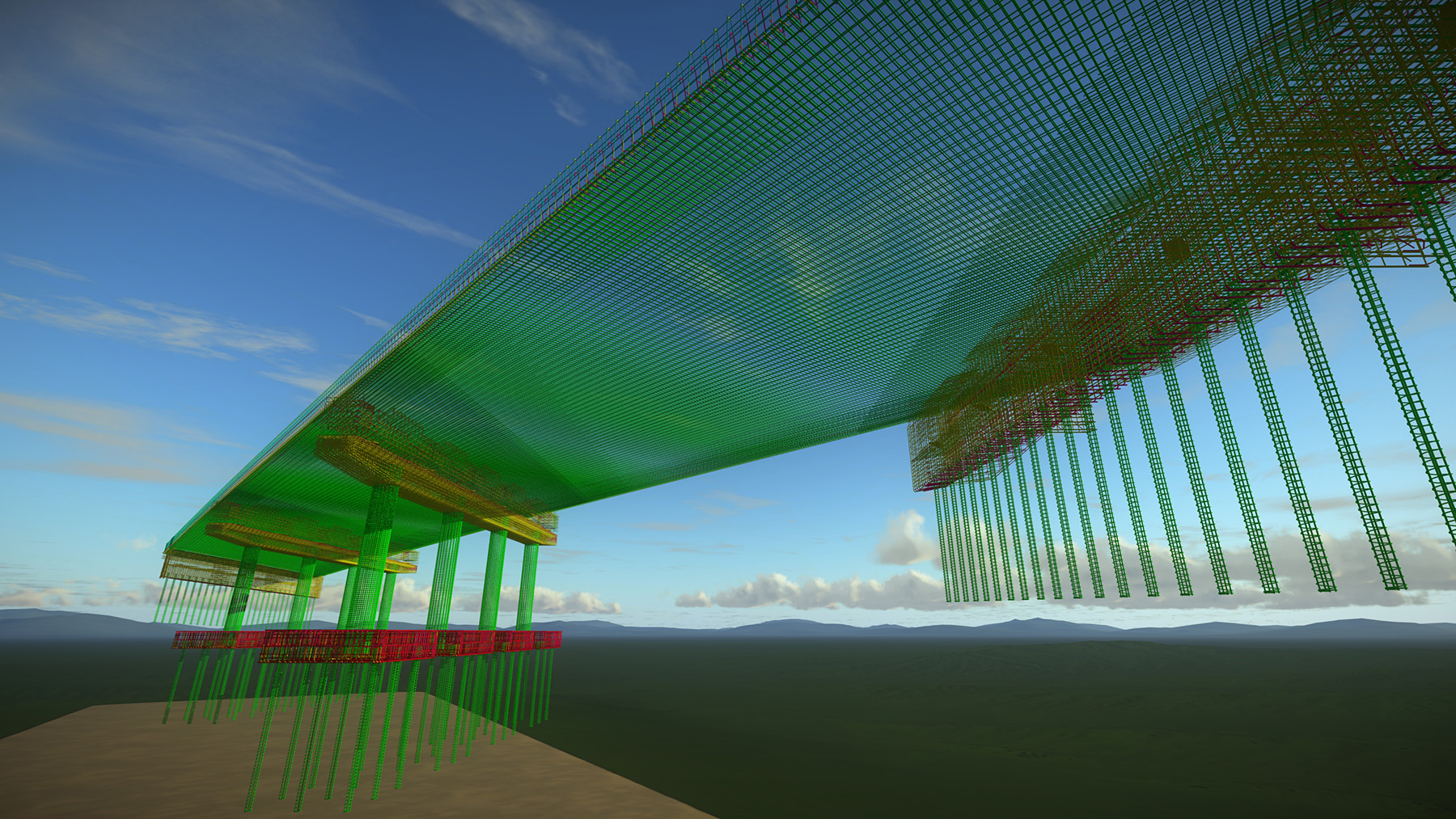

On a wider scale, model-based design involves shifting thinking from plan-centric work to data-centric work, where information can be accessed and used in multiple ways. Instead of drawing 2D lines on paper for a specific project, infrastructure assets will be designed as 3D objects that virtually represent the physical asset, with all the information needed not only to construct it but also to inspect and maintain it.

Digital delivery offers a solution for taking data away from silos within organizations and providing it when it is needed to whomever needs it.

As engineers are accountable for their designs, this data-centric understanding is particularly critical for models used as contractual, signed and sealed deliverables. Engineers need to understand what they are signing and certifying and how it will be used. Just as importantly, engineers need to understand how these data will be sealed to ensure they are secure and match the information that was signed.

A digital future is coming

All this ongoing work points to an industry transition that shows no signs of slowing. To use a transportation metaphor, the train has left the station, it is gathering steam, and there is no turning back.

Recognizing this, national organizations such as AASHTO and the FHWA have dedicated significant time and resources to advancing national standards. The BIM for Bridges and Structures Pooled Fund study led by HDR, for example, is being supported by 24 states. The goal is to standardize the process for BIM design and construction of transportation projects by embracing internationally recognized and International Organization for Standardization-compliant open data standards. A larger BIM for Infrastructure Pooled Fund study is scheduled to start this year to expand these efforts.

The FHWA has invested more than $35 million on BIM-related studies and deployment through research and Every Day Counts initiatives. And the FHWA, AASHTO, and others are moving toward a national open data standard that will be seamless across digital applications from software providers, collaborating closely with buildingSMART International and the Open Geospatial Consortium.

This ongoing digital delivery shift in transportation infrastructure will touch every part of the project delivery process, from design to construction/fabrication to operations and maintenance and long-term asset management. And it will affect engineers and organizations whether transportation is their focus or not. Sectors from geotechnical to utilities will need to adapt to this new method of receiving and transmitting information if they plan to continue to collaborate with transportation agencies.

The good news is that the benefits are tangible and substantial, allowing transportation agencies to harness the power of data to improve the efficiency of their work and better create and maintain the nation’s complex transportation systems.

The future of the infrastructure and engineering industry is a digital one. The rate of change will only accelerate from here. Agencies that begin transitioning their organizations and engineers who adapt to this reality will find a bright future awaits.

SIDEBAR

What do these plans look like?

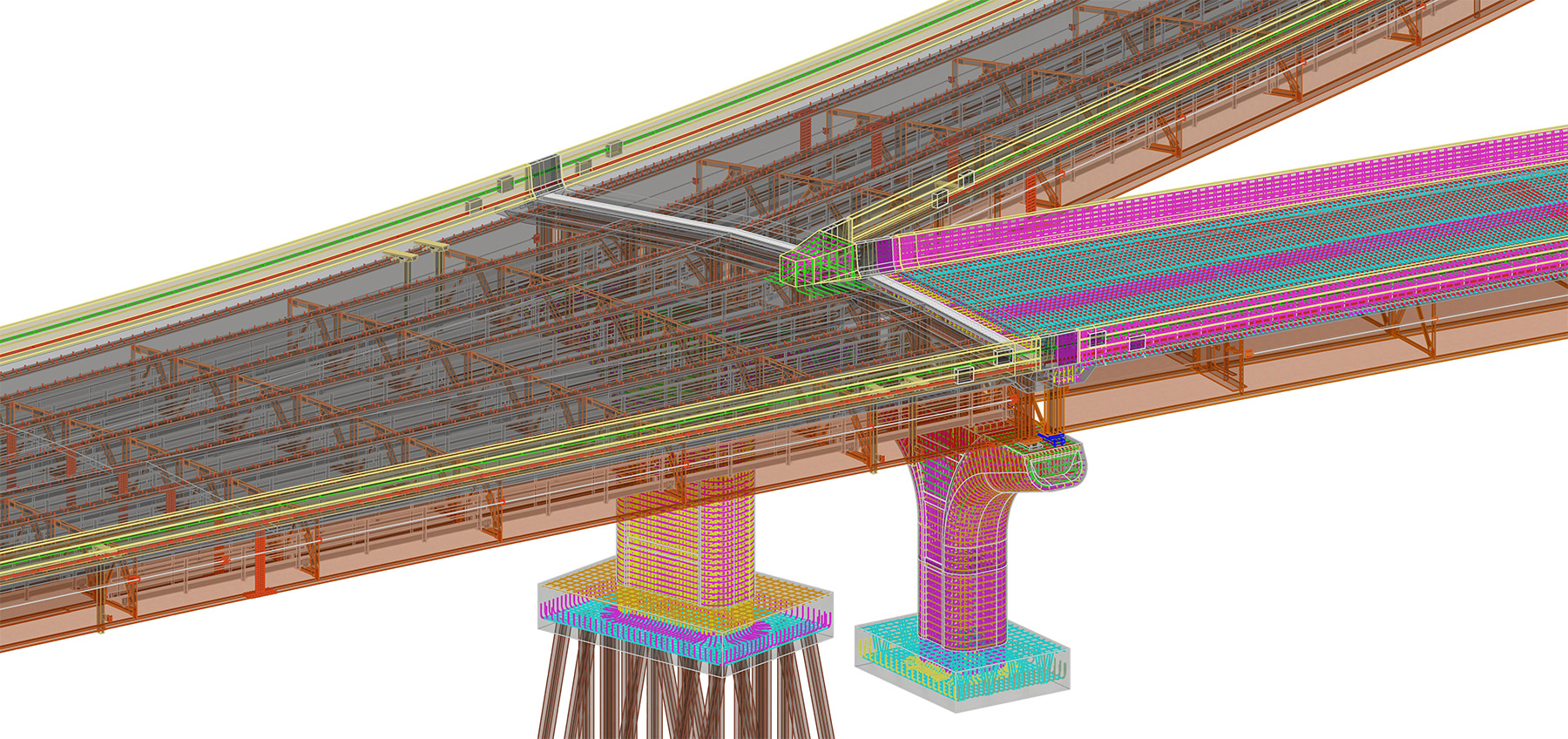

Rather than traditional plan sheets and cross sections, digital plans are often a combination of 2D and 3D information. On screen, some views look similar to traditional plan sheets, with line work, notes, callouts, and stationing.

But with 3D plans, users are also able to zoom in on sections or navigate through the entire project. Layers can be turned off or on to focus on specific aspects. For engineers in offices, these plans will likely be navigated on desktop computers. Contractors, inspectors, or engineers in the field can use tablets with viewer apps.

One key difference is the ability to view the design in 3D as well as 2D. This allows better communication of design intent. When combined with GPS and location data, staffers in the field can even view the model from current perspectives to match what they are seeing to the model. The model includes all the information commonly found in plan, profile, and cross section sheets — stations, elevations, dimensions and parameters, and pay-item information.

The 3D models can also have files attached when helpful, such as PDFs of corresponding standard drawings, spreadsheets with calculations, and more.

Alexa Mitchell, P.E., is HDR’s transportation BIM program manager, based in Phoenix. Jennifer Steen, P.E., PMP, ENV SP, is HDR’s highways and roads BIM director, based in Philadelphia. Will Sharp, P.E., PTOE, is HDR’s director of highways, based in Omaha, Nebraska.

This article first appeared in the March/April 2023 issue of Civil Engineering as “A Fully Digital Delivery for Transportation.”