By Robert L. Reid

In Brazil, the city of Curitiba adopted a master plan six decades ago that has made it a modern leader in urban development, sustainable living, and the fight against climate change.

The city of Curitiba, capital of the state of Paraná in southern Brazil, has established a history of excellence in urban planning and good practices, enhancing local solutions for urban development and, above all, human development,” according to Luiz Fernando Jamur, the municipal secretary of public works in Curitiba.

Jamur, a civil engineer, explains that Curitiba’s planning efforts rely on a master plan, created in 1966, that focuses on several key principles. These include public transit, the road system, and land use that promotes social and economic development together with environmental preservation.

This ongoing plan, which has been updated several times, has enabled the organized and sustainable development of a city that has over 1.7 million inhabitants, as well as a metropolitan region with 3.5 million people within more than two dozen municipalities, Jamur notes. With urban areas playing a critical role not only in combating global warming but also in improving the lives of their inhabitants, the Curitiba master plan promotes sustainability, “with public engineering projects serving as the materialization of (its) citizens’ collective dream.”

In 1965, the city created a municipal agency known as the Institute of Research and Urban Planning of Curitiba, or IPPUC, to monitor and guide the implementation of what was then the proposed master plan, says Jamur, a former president of the agency. IPPUC is assisted by the Curitiba City Council, known as Concitiba, which was established in 2007 to bring together representatives from the government and various stakeholders. Concitiba’s mission is to ensure that all discussions of public policy regarding the master plan “aim to build a sustainable city from a social, economic, and environmental perspective,” according to an English-language translation of the website of the Curitiba City Hall, the Prefeitura de Curitiba.

Smart and sustainable

In May 2024, an ASCE delegation visited Curitiba as part of the Society president’s annual tour to sites in Region 10, which encompasses 34,000 members in 174 countries outside the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Brazil was the destination last year for ASCE President Marsia Geldert-Murphey, P.E., F.ASCE; ASCE executive director Thomas W. Smith III, CAE, ENV SP, NAC, F.ASCE; and others, who traveled first to São Paulo, then Curitiba.

In Curitiba, the delegation visited the IPPUC headquarters, where they toured a control center for the city’s Hipervisor system — a “new, innovative tool that will support the city’s planning,” says Nives McLarty, Aff.M.ASCE, senior manager, global programs at ASCE, who organized and then documented the trip. Hipervisor is a public data collection and sharing platform that can amass, process, and distribute information to help city hall officials anticipate problems that may affect the environment, proactively mitigating situations such as traffic congestion or the effects of heavy rains, explains the city hall website.

In addition, the delegation learned how the city’s “creative, environmentally friendly solutions to urban planning issues have been effectively alleviating poverty,” says McLarty. “Curitiba has also done well curbing emissions and protecting the area’s biodiversity. With 52 sq m of green space per person, Curitiba has one of the highest densities of urban green space in the world and is known as the environmental capital of Brazil.

“This is not only because of its array of parks but also because ... it has had progressive city governments that have been innovative in their urban planning. The emphasis on protecting the environment has produced an efficient public transportation system and a comprehensive recycling program that are being used as models for cities around the globe,” says McLarty.

Renan Gustavo Pacheco Soares, Ph.D., Ing., R.Eng, M.ASCE, the president of ASCE’s Brazil Group in 2024, was a member of the delegation. He notes: “Curitiba is an example that with good projects, qualified professionals, dedication, government incentives, and a vision for the future, it is possible to go further in terms of social evolution. It encourages us to expand this future world vision throughout our country.”

People in motion

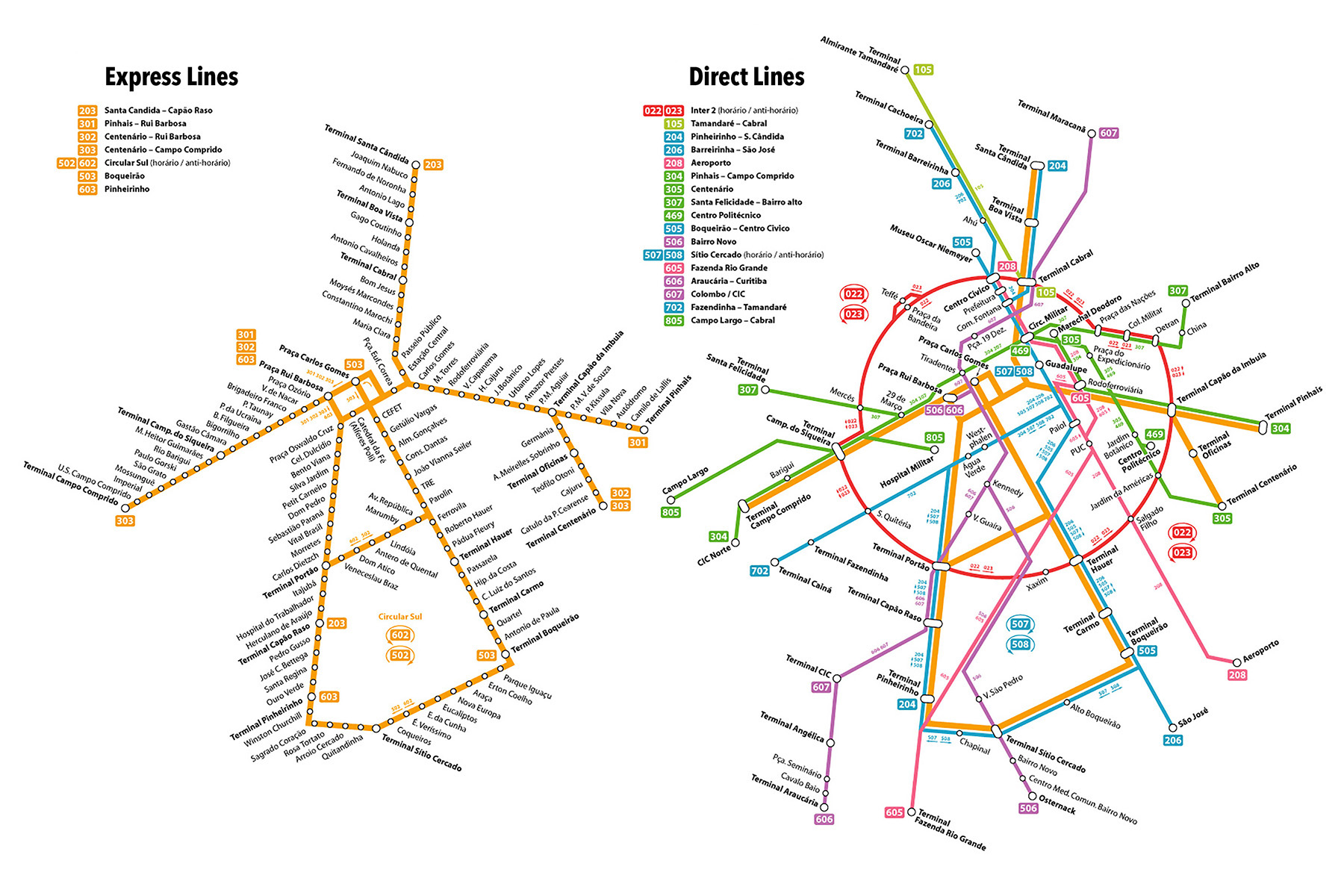

In Brazil and across South America, Curitiba has become a transportation pioneer due to the creation of a pedestrian-only street in the city center in the early 1970s, as well as the launch of transit corridors with express buses using dedicated lanes, alongside lanes for slower traffic, to promote greater density, Jamur says. This system, combined with terminals and a single fare system, heralded an approach now known globally as bus rapid transit, or BRT, he adds.

Curitiba’s transportation model continues to evolve with the implementation of the Sustainable Mobility Program, which aims to adopt fleets of electric buses and promote intermodality along an East-West corridor (connecting Curitiba to Pinhais, a municipality roughly 8 km to the east) and a circular line that integrates the critical routes of the BRT system. Such decarbonization efforts anchor Curitiba’s Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Plan, known as PlanClima, which is aligned with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and aims for carbon neutrality by 2050, Jamur says.

The goal is for 33% of Curitiba’s bus fleet to be zero-emission vehicles by 2030, and 100% by 2050, according to the website.

Among the electromobility efforts under way in Curitiba are the East-West BRT Capacity and Speed Increase projects and the Inter 2 project. Along the East-West BRT route, improvements will enable intermodal transportation, encouraging the use of bicycles and promoting greater walkability and accessibility in the areas surrounding the BRT stations.

In addition to making the BRT system more efficient, new terminals will expand service. For example, the new Capão da Imbuia terminal, which will be built next to an existing facility, will increase the number of lines offered and carry 49,000 passengers per business day. The new terminal will also have bicycle storage and retail areas.

The road system along the East-West BRT route will also undergo improvements. One of the most important is the creation of the Olga Balster and Nivaldo Braga dual carriageway, connecting the Tarumã and Cajuru neighborhoods. With the new lanes, traffic will be more agile, and bottlenecks during peak hours will be reduced, improving flow and safety for drivers and pedestrians. The area will also feature improved accessibility with new sidewalks.

At another point, in Cajuru, Nagib da Silva Street will be closed to vehicle traffic between Filipinas and Ceilão streets, which will also form a two-way road to improve local traffic flow. The project will facilitate active mobility, giving priority to pedestrians and improving access to the city center.

Inter improvements

The Inter 2 project, covering a 38 km route and serving multiple neighborhoods, is designed to improve the operating standards of the two bus lines that carry the most passengers in Curitiba. These two lines will feature electric buses and infrastructure improvements to the BRT lanes on the route that connects the city’s structural transportation axes in an area covering 580,000 inhabitants.

The planned Inter 2 improvements to road infrastructure and transportation equipment will also include 70 km of roads that will be opened or upgraded, 30 km of exclusive bus lanes, 13 new stations, and the construction of the Santa Quitéria mini-terminal, among other works. These improvements are expected to increase operational speed and expand the capacity of the lines from 155,000 passengers per day to 181,000 per day.

In addition to electric buses, the Inter 2 project will provide intermodal integration of the new stations with micromobility, such as bicycles and electric scooters, car-sharing, and app-based transport systems. Solar panels on the stations will provide power for automatic doors, air conditioning, lighting systems, Wi-Fi, electronic ticketing, recharging electronic devices, and an intelligent system for transferring internal monitoring data (such as the number of users and electronic ticketing). The location will also serve as a base for recharging other modes of transport, such as scooters, bicycles, and car-sharing.

Stations will also have benches, raised gardens, and seating areas, with space for users to rest, wait, and socialize. “These uses expand the potential of the Inter 2 line, the functionality of the station, and the user experience,” says the website. “The union of the station structure and its functional surroundings creates a unique environment in the urban space, as an open-air station and a nodal point in the city.”

Green spaces

PlanClima will also include an expansion of parks along watersheds in Curitiba and the surrounding region. In addition, Curitiba worked to reduce the possibility of flooding during intense rain events via 30 macrodrainage projects involving six regional river basins. Other efforts to prevent flooding include cleaning rainwater collection infrastructure to prevent blocked pipes.

Several new parks will also provide floodable green areas. This will help preserve natural resources to maintain and improve soil waterproofing and reduce the risk of flooding in Curitiba. “The idea is to use the natural capacity of lakes, trees, bushes, soil, and storm drains to allow water to flow to places where it does not cause major damage to residential areas,” the website says. A series of linear parks have also been created along the city’s six rivers to help preserve river drainage strips and prevent flooding.

Another key water-related project in Curitiba, known as the Water Reserve of the Future, will connect old mines and other spaces to create a series of lakes — expected to reach roughly 26 km in length — that can supply water to the city’s population in times of drought.

“It is worth remembering,” the website says, “that Curitiba’s green areas, in addition to helping to combat floods ... also have the function of reducing ‘heat islands’ and pollution. Trees and vegetation, in addition to producing oxygen, help regulate temperature and humidity. As added benefits, they reduce ultraviolet radiation and traffic noise, being true oases for both plant and animal species, not to mention being perfect places for Curitiba residents to relax and practice sports.”

Curitiba is actively working to expand its green spaces, with plans to plant 500,000 new trees in the coming years.

Clean power

Among Curitiba’s strategies to combat and mitigate climate change are various clean energy efforts. The Caximba Photovoltaic Park, also called the Curitiba Solar Pyramid, is a photovoltaic project installed in a deactivated landfill that generates enough clean energy to provide 30% of the energy consumed by the city’s public buildings.

Solar panels have also been installed at various buildings, including municipal schools, as well as on more than 100 affordable homes. There is also a mini hydroelectric plant at a city park that uses a 3.5 m high waterfall — created by the spillway of the park’s lake — to generate energy through a helical screw, according to the site.

Smarter living

An entirely new “smart” neighborhood is also planned in Curitiba. The Bairro Novo da Caximba will be the first smart neighborhood in Brazil, encouraging the resettlement of more than 1,100 families. The region had long been occupied illegally, with people living along flooded areas of one of the largest river basins in Paraná. With the new projects, families will be transferred to land in areas suitable for development. A flood containment dike and linear park will be constructed, along with roads and other transportation infrastructure, sanitation, and water and electricity systems.

An entirely new “smart” neighborhood is also planned in Curitiba. The Bairro Novo da Caximba will be the first smart neighborhood in Brazil, encouraging the resettlement of more than 1,100 families. The region had long been occupied illegally, with people living along flooded areas of one of the largest river basins in Paraná. With the new projects, families will be transferred to land in areas suitable for development. A flood containment dike and linear park will be constructed, along with roads and other transportation infrastructure, sanitation, and water and electricity systems.

The new homes will feature a photovoltaic system for microgeneration of solar energy. A new reservoir will collect rainwater for reuse, while the new roads will be constructed with permeable paving and slopes designed for microdrainage. This will keep the soil dry and channel rainwater to the bed of a nearby river to help control flooding.

Sustainable solutions

City leaders promote the widest possible range of sustainable practices. Their efforts even extend to the implementation of community gardens that meld the city’s green infrastructure with its indigenous crops. The gardens will include some 170 spaces for growing fruits and vegetables and beehives for the region’s native stingless bees.

The city promotes recycling through a public information program called Garbage Collection That Isn’t Waste, and it also stresses the reuse of water and the benefits of renewable energy.

The gardens and recycling efforts are united in the city’s Green Exchange program, which enables “any citizen, without needing to register, (to) exchange recyclable materials such as paper, cardboard, glass, metals, and even used household oil, for fruits and vegetables,” the website explains. “Every month, around 290 tons of recyclable materials and 3.5 thousand liters of oil are no longer discarded incorrectly and become food on the tables of Curitiba’s citizens.”

There are also plans in the works to implement a new waste treatment system for the Curitiba region that will convert urban waste into fuel for cement manufacturing, replacing petroleum coke. This fuel replacement, combined with the volume of waste that will no longer go to the landfill, “represents a reduction in the emission of 1.2 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere for each ton of (urban waste) processed by cement plants,” the website explains.

Curitiba also hopes to electrify the trucks used in its urban solid waste collection service, which will garner appreciable environmental gains. “Compared to an equivalent diesel unit, which (travels) approximately 50,000 km per year, an electric truck” consumes approximately 20,000 liters less of fuel, “(eliminating) the emission of 60 tons of (carbon dioxide).”

The programs mentioned here are just some of the efforts toward sustainability and planning in Curitiba, which Jamur describes as a constantly developing urban platform. “Recognized for its planning history, our city prioritizes continuous progress,” Jamur explains. “We have much to teach and much to learn to meet the challenge of making, through engineering, the collective dream of a better city come true every day.”

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “Sustainably Urban.”