By Gary Collins, PLA, and Taylor Critcher, PLA

The built environment is changing faster than ever. To ensure it is developed in a thoughtful manner, many agencies and developers have turned their attention to large-scale planning efforts that take a holistic approach to how the overall development will fit into the natural and surrounding environment.

Master planning is certainly not a new concept, but the wide range of techniques and tools now available is allowing us to develop more thoughtful plans. Technology such as geographic information systems, or GIS, can map and analyze land characteristics quickly; 3D modeling software helps us visualize what the plan will look like; and applications like SiteMarker construction reporting software help us gather early site information. That information includes topography and existing conditions to help inform planning efforts.

We also rely on industry partners including geotechnical engineers, architects, landscape architects, and traffic engineers, to name a few, who are all part of the master planning team and process.

It is important to start with the significance and benefits of master planning. Initially, master plans set the overarching vision for a site, ensuring that all parts of a potential large-scale development work seamlessly. In most cases, master plans provide an owner or developer with a solid idea of the most efficient land use to make the project work.

Master plans act as a framework that spells out the locations of infrastructure, open space, utilities, and developable land. They provide an understanding of how a long-term project can or should be phased from an implementation standpoint. Whether required by a local ordinance or not, master plans often seek input from local agencies and community stakeholders to ensure that any concerns or needs are understood and to gain community support.

Effective and well-thought-out master plans protect, enhance, or rebuild the natural parts of a site to create long-term value and identity. These components work together to attract the attention of potential investors, tenants, and partners.

Across the Southeast, master plans are shaping how cities, towns, and in some cases industrial campuses come to life. Civil engineers and planners are becoming increasingly important in the planning and implementation of these long-range efforts. Examples of master-planned projects include Camp Hall, near Charleston, South Carolina; Mauldin City Center, near Greenville, South Carolina; and Wakefield in Troutman, North Carolina. Each of these master plans — developed by the SeamonWhiteside team — demonstrates how thoughtful design and understanding can reshape landscapes and lives.

Planning an industrial camp

Camp Hall, once an agricultural site, is a 6,800-acre industrial commerce park in Berkeley County, approximately 45 minutes outside of Charleston. Camp Hall is also located adjacent to Volvo Cars’ only North American facility. The new industrial park includes nine campuses with a range of development acreages. The largest of the campuses is 600 acres and will be the home of the Redwood Materials battery recycling factory.

SeamonWhiteside has provided master planning, civil engineering, and landscape architecture services since the project began roughly 15 years ago, most recently for Santee Cooper, a South Carolina power and water utility that purchased the industrial park in 2015. As part of the overall development agreement, the project does not include residential properties, although future land uses in the county could allow for residential and community support services.

Camp Hall was designed on three principles:

- Economy and commerce: Creating a meaningful, relevant, and contextual place, no matter the use. We kept this principle in mind during the technical design and engineering of the industrial park, which resulted in more green infrastructure for handling stormwater conveyance. It also helped guide the physical organization of the campuses and buildings. Ultimately, it resulted in a more collective engineering strategy rather than the creation of isolated parcels.

- Community: A vibrant and healthy place can only lead to an enhanced community.

- Ecology: The idea that everything comes from nature guided the overall design. Measures such as surveying the flora and fauna of the area and providing natural areas that could continue to serve as habitat for the local animal species helped achieve this goal, which will hopefully enhance users’ experience of working in the industrial park and provide quality open space for their enjoyment.

The project’s open-space strategy resulted in the conservation of nearly 2,600 acres of land, including the restoration of 356 acres of wetlands and the protection of 1,265 acres of freshwater wetlands and community gathering spaces.

In South Carolina, wetlands must be protected, but a limited acreage can be filled in and mitigated. Consequently, the project included an extensive wetland protection and mitigation strategy that was approved by state regulators. Because Camp Hall is located at the headwaters of a regional watershed, understanding how to handle stormwater was a critical component of the plan. Part of the solution involved the restoration of a hardwood wetlands area by removing a pine forest — once part of a logging operation — and the diversion of stormwater to the wetland areas through a series of ponds and berms.

The old logging roads typically had large ditches along their edges to drain the wet areas and create a more favorable soil condition for the pines. We used a blended strategy of open drainage swales, piping, and infiltration to accommodate the stormwater requirements and create an enhanced habitat that more closely resembled the indigenous one.

Interconnected walkability was another goal of the master plan. Toward that end, many of the logging roads were surveyed and used for bike and walking trails — some were left as dirt and gravel trails, while others were improved to become multiuse asphalt trails. A total of 15 mi of interconnected trails now serve the development and are accessible to the greater community.

Though primarily an industrial site, Camp Hall includes spaces open to the public to encourage “cross-pollination” between the businesses and the community. At the heart of the development is the new Avian Commons, a walkable village-like area that includes soccer fields, volleyball courts, pavilions, outdoor fitness equipment, and a playground.

The master plan also anticipates commercial development that will include conveniences such as a day care center, a hotel, restaurants, and a general store. These will create a work/play environment that supports industry and the community.

Because Camp Hall was envisioned as a people-first development, the project used online and in-person surveys to solicit feedback from the community and potential end users. The idea was to better understand the needs and wants of the people who would work there as well as the companies operating at the site. Camp Hall is a living model that illustrates how commerce, ecology, and community can thrive together.

Designing a downtown for people

Located just under 10 mi from Greenville, the city of Mauldin is experiencing another transformation. Mauldin, a roughly 12 sq mi area in upstate South Carolina, has an estimated population of 28,000 residents. But the city has experienced a 65% increase in population since 2000, and it is projected to reach 40,000 residents by 2030, according to the Mauldin Economic Development department.

Historically defined by a car-centric layout with few traditional downtown gathering spaces, Mauldin is now undergoing a visionary shift that trades cars for community in order to reclaim the heart of the city.

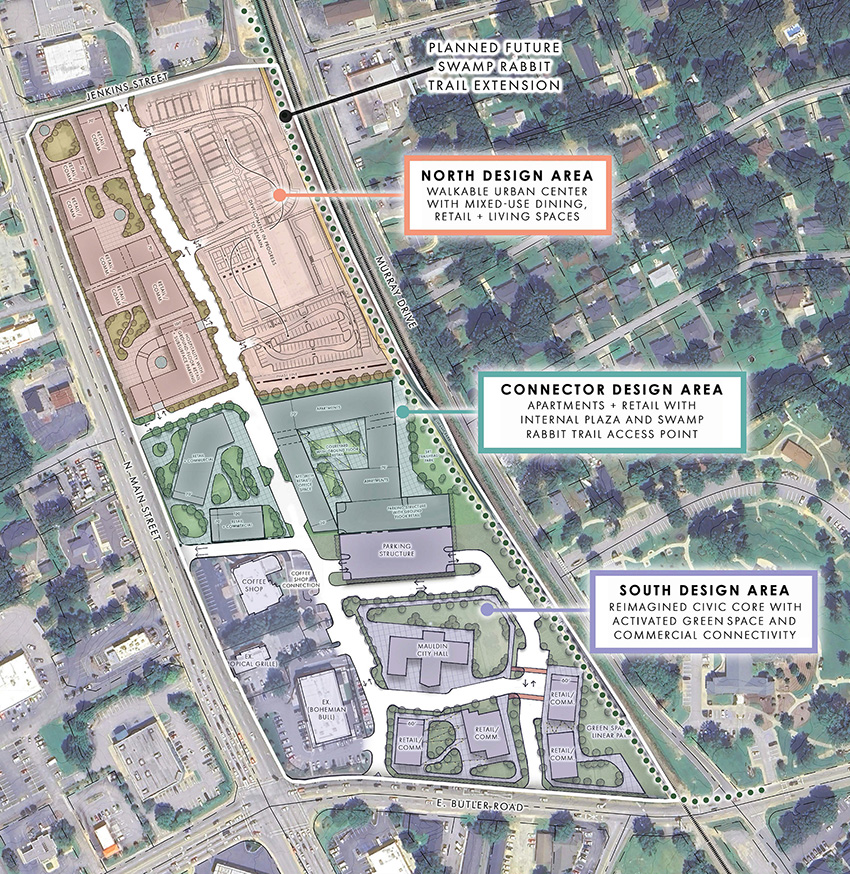

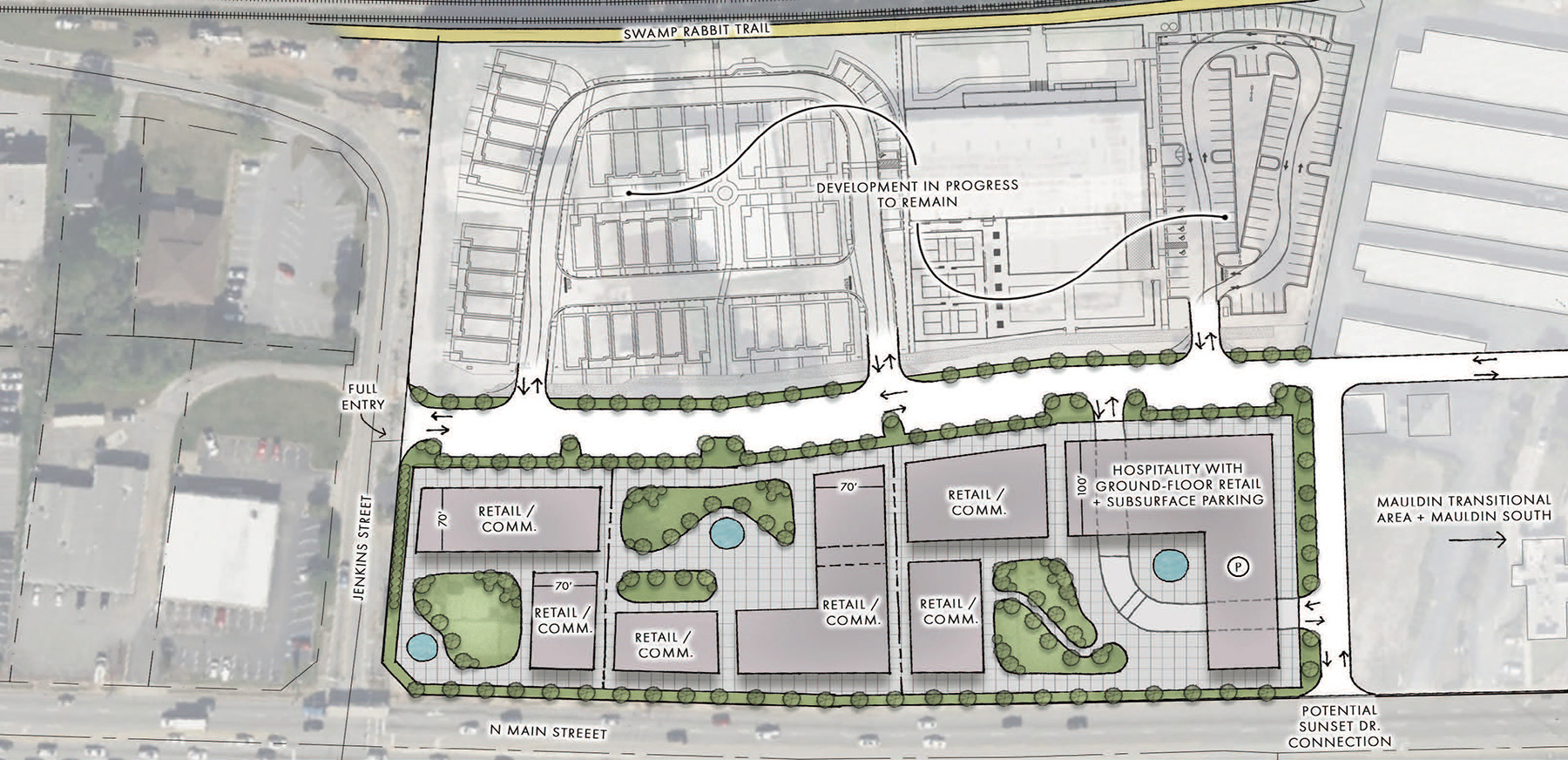

In 2024, SeamonWhiteside collaborated with Mauldin’s city leaders to develop a comprehensive master plan for Mauldin City Center, a downtown area intended to bring together retail, dining, housing, and green spaces in a walkable, people-first environment.

Because Mauldin was not originally formed around a traditional downtown, with a defined main street identity, one of the project’s primary goals was to reclaim space and plan for future development to establish such an identity.

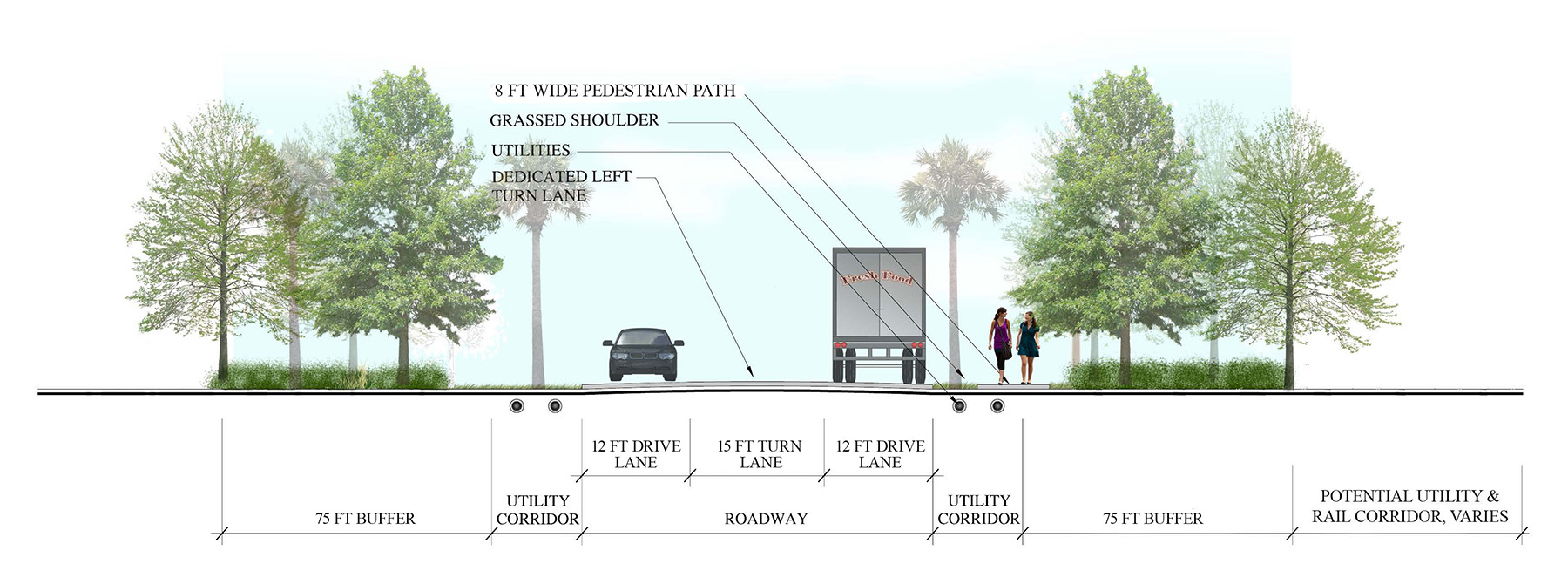

Another key piece of the engineering effort was coordination with the South Carolina Department of Transportation on the future access options for the site. Because of the reliance on cars as the primary means of transport, there were already roadway improvement projects underway in the area, so planning around this new transportation infrastructure was key for mapping out the future of City Center.

Wide sidewalks, pedestrian crossings, and traffic-calming measures make walking the preferred mode of transportation in City Center. The plan incorporates 8 ft wide walkways around the main retail elements, with on-street parking, paver-accented raised crosswalks, and tree-lined streets.

The plan also links to a future extension of the existing Swamp Rabbit Trail, a 28 mi trail system connecting Greenville to Travelers Rest, South Carolina. This trail is used by runners, walkers, and bikers at all times of day and is lined with retail and dining options in many key sections. The trail is planned to reach Mauldin as well, with the expansion running through the heart of the City Center development, connecting the new downtown to the region’s broader greenway system.

Green spaces, plazas, and gathering areas are central to the plan, with flexibility a key component. Rather than provide one final master plan, the SeamonWhiteside team created five unique design typologies for City Center. What each plan has in common is the inclusion of three primary green areas. The largest connects Mauldin’s existing city hall to the proposed retail and dining areas and would occupy up to three quarters of an acre.

The other green spaces will range between a quarter and half an acre. Mauldin is considering amenities such as a water feature, seating pavilions, a small outdoor stage, and amenities for bikers along the Swamp Rabbit Trail frontage.

Although these areas will host events, markets, and community programming, they will also play a critical role in the region’s stormwater management plan through underground detention, rain gardens, and other measures.

Harmonizing with nature

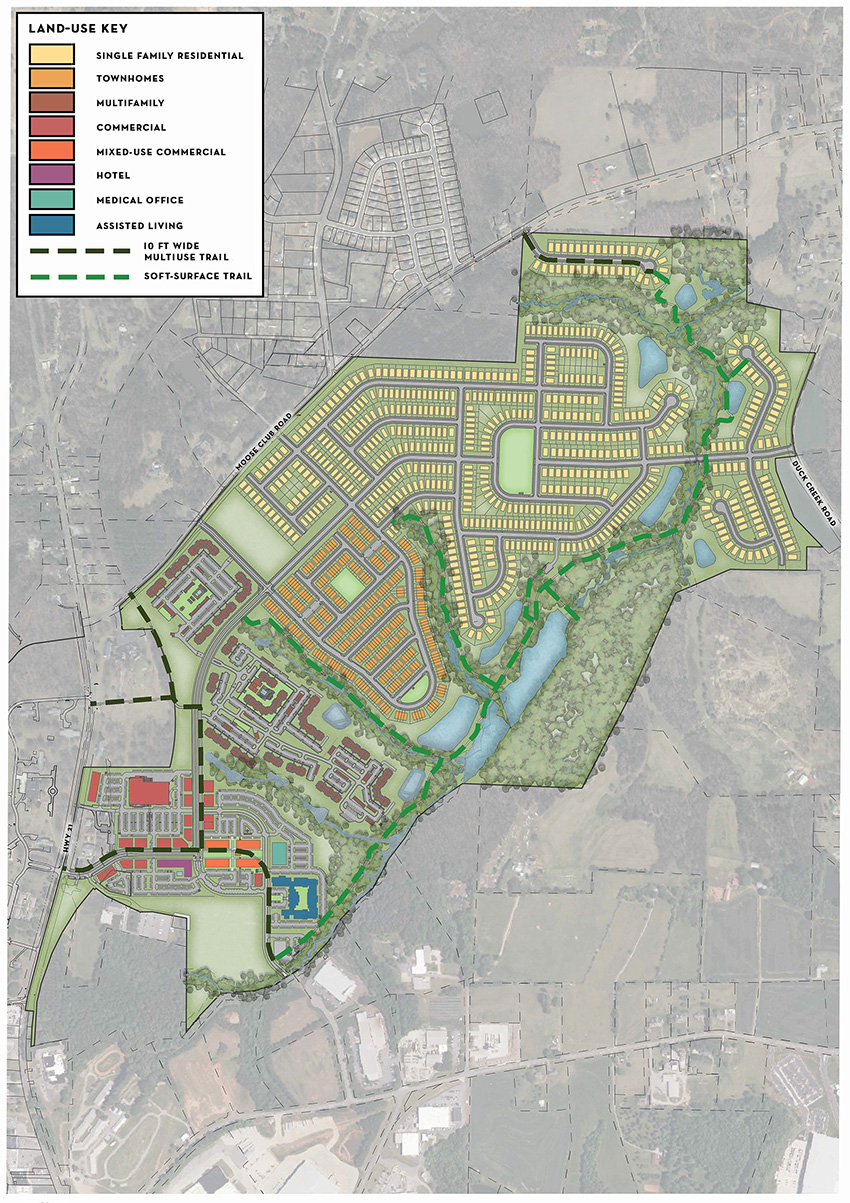

Throughout the Southeast, towns and cities adjacent to larger metropolitan areas are experiencing explosive growth, which creates the challenge of building lasting new communities that will have a positive impact on existing communities. At Wakefield, an 800-acre development in Troutman, North Carolina, 35 mi north of Charlotte, the master plan aimed to do just that.

The master plan for Wakefield approached the site with sensitivity to both the town’s growth trajectory and its rural character. The effort relied extensively on a close collaboration among SeamonWhiteside’s civil engineers and landscape architects and a variety of stakeholders and design professionals, including a team of private developers, community members, environmental consultants, geotechnical engineers, and traffic consultants.

The resulting master plan was simultaneously ambitious and thoughtful, providing a range of housing options, walkable access to amenities, and robust greenway connections that knit the proposed development into the existing fabric of Troutman.

The SeamonWhiteside team began the process with multiple days of design workshops with the client, North Carolina developer Prestige Corporate Development LLC. The goal of these brainstorming sessions was to explore ways of weaving the intended development program into the existing site and surrounding community prior to seeking approvals from the town’s leaders.

Because the proposed Wakefield development will likely double Troutman’s existing population of approximately 4,000 people, it represents a pivotal moment in the town’s future.

SeamonWhiteside knew that the approval processes would potentially be turbulent, involving multiple meetings with the community, the planning board, and the town council.

To showcase the project to its best advantage, the team created an appealing presentation using tools such as GIS, AutoCAD, Adobe Creative Suite, SketchUp, and Lumion. The effort ultimately proved worthwhile, as the project gained the necessary approvals and is on its way to becoming a finished project.

One of the critical features of the master plan is diverse housing for a diverse community. The plan includes approximately 700 traditional single-family homes, 400 townhomes and apartments, 450 market-rate multifamily units, and 800 age-restricted homes.

This mix of housing types brings together residents of varying income levels and backgrounds while providing residents with the ability to transition into different housing types as needed.

The plan also includes centralized commercial and retail with a pedestrian-focused, open-air shopping center known as Barium Commons. It will provide convenient access to eating and drinking establishments, a grocery store, shops, and services for residents that include self-storage, medical offices, and hospitality.

There will also be a central open space with play areas for children, spaces to rent for events, and space for musical performances and community gatherings.

One of the plan’s standout features is access to open space, including approximately 50 acres of preserved and improved natural areas. Although the development will provide traditional roadways and sidewalks, residents will also have access to approximately 2.5 mi of soft-surface and paved walkways if they wish to take a more scenic and enjoyable route to their destinations. The proposed paths will connect to Troutman’s existing greenway system and also allow access to the Carolina Thread Trail, a regional network of roughly 425 mi of interconnected trails in North and South Carolina.

By integrating development with nature and creating a true mix of uses, Wakefield will enable the town of Troutman to grow without losing its character.

The SeamonWhiteside team is also in the design phase for approximately 6,500 linear ft of off-site force main, a sewer lift station, and about 7,500 linear feet of gravity sewer main to serve this development.

Creating the future

Across these three projects, several powerful themes emerged that demonstrate how thoughtful master planning can shape the future. For example, it is clear that walkability is a game changer. All three projects prioritized the pedestrian experience. Trails at Camp Hall, sidewalks in Mauldin, and greenways in Wakefield all reflect a shift from car dependency toward healthier, more connected communities.

Nature is not an afterthought. From wetland restoration at Camp Hall to the natural preserves in Wakefield, integrating nature is key. These plans do not treat the environment as something to be preserved at the edge; they weave it into the heart of the community.

Whether it is the public areas within Camp Hall’s industrial setting or flexible plazas in Mauldin, placemaking creates identity. Master plans are increasingly recognizing the need for places that feel unique, memorable, and tied to a local culture.

Incorporating mixed uses creates opportunity. When places to live, work, shop, and play are interconnected, communities become more vibrant and sustainable.

Master planning is a team effort. It takes vision, collaboration, and expertise to bring these kinds of projects to life. Civil engineers, landscape architects, architects, government officials, private developers, and community stakeholders are all involved in these efforts, bringing essential perspectives.

At its heart, master planning is not just drawing lines on a map or talking about ideas. It is about developing a shared vision and creating a framework that puts people at the center.

Gary Collins, PLA, is a vice president and Taylor Critcher, PLA, is a director at SeamonWhiteside.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “Building Communities with Purpose, Vision, and Heart.”