By Jenny Jones

The desire among project owners, design teams, and other stakeholders to deliver sustainable infrastructure is not new. After all, sustainable projects can lead to long-term cost savings and recognition within communities. But understanding what truly constitutes a sustainable project has often been unclear. Is using recycled concrete enough to make a project sustainable? What about planting trees to offset a project’s embodied carbon or involving community members to make it socially responsible?

In 2023, owners and delivery teams gained clarity on these questions, thanks to a new ASCE standard that defines baseline criteria for achieving sustainable infrastructure solutions.

ASCE/COS 73-23 Standard Practice for Sustainable Infrastructure is the only standard of its kind to define sustainability in infrastructure programs and projects. ASCE’s Committee on Sustainability published the standard to establish baseline requirements for sustainable infrastructure development not just at project completion but also throughout the entire project life cycle. Applicable to infrastructure of any type and size and designed for everyone involved in infrastructure development — from owners and operators to engineers and contractors — the standard includes 29 performance-based outcomes, 19 of which must be met for a project to be considered sustainable from cradle to grave.

ASCE/COS 73-23 is a non-mandatory standard; however, a new committee is working on an update that could change that. Still, development teams that follow the standard can point to it as proof that their projects are sustainable, potentially unlocking benefits such as increased access to funding, stronger community support, better alignment with public sustainability goals, and more resilient, cost-effective projects over time.

“Project teams can look at this standard and say, ‘If we meet 19 of these 29 outcomes and perform a life-cycle cost analysis to achieve the lowest equivalent life-cycle cost, this project will meet the criteria for sustainability,’” explains Terry Neimeyer, P.E., BC.EE, ENV SP, Dist.M.ASCE, chair of the ASCE Committee on Sustainability. “It allows them to build sustainability into their projects from the start so that they end up with the lowest life-cycle cost solution.”

Recognizing a need

Although the Committee on Sustainability officially published ASCE/COS 73-23 two years ago, it recognized the need for a standard to define what constitutes sustainable infrastructure much earlier. According to Neimeyer, the committee began having conversations about a formal standard as early as 2011. That same year, ASCE joined forces with the American Public Works Association and the American Council of Engineering Companies to establish the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure, an education and research nonprofit.

At that time, ASCE encouraged ISI to develop a sustainability standard to align with the Society’s mission of leading the civil engineering profession to advance and protect the health, safety, and welfare of all. But, according to Neimeyer, who is a founding ISI board member and former chair, the organization was too small and new to launch such a major undertaking — one that was sure to require several dedicated years with major costs. ISI ultimately collaborated with the Zofnass Program for Sustainable Infrastructure, once part of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, to create and finalize the Envision Sustainable Infrastructure Framework, which is a sustainability rating tool.

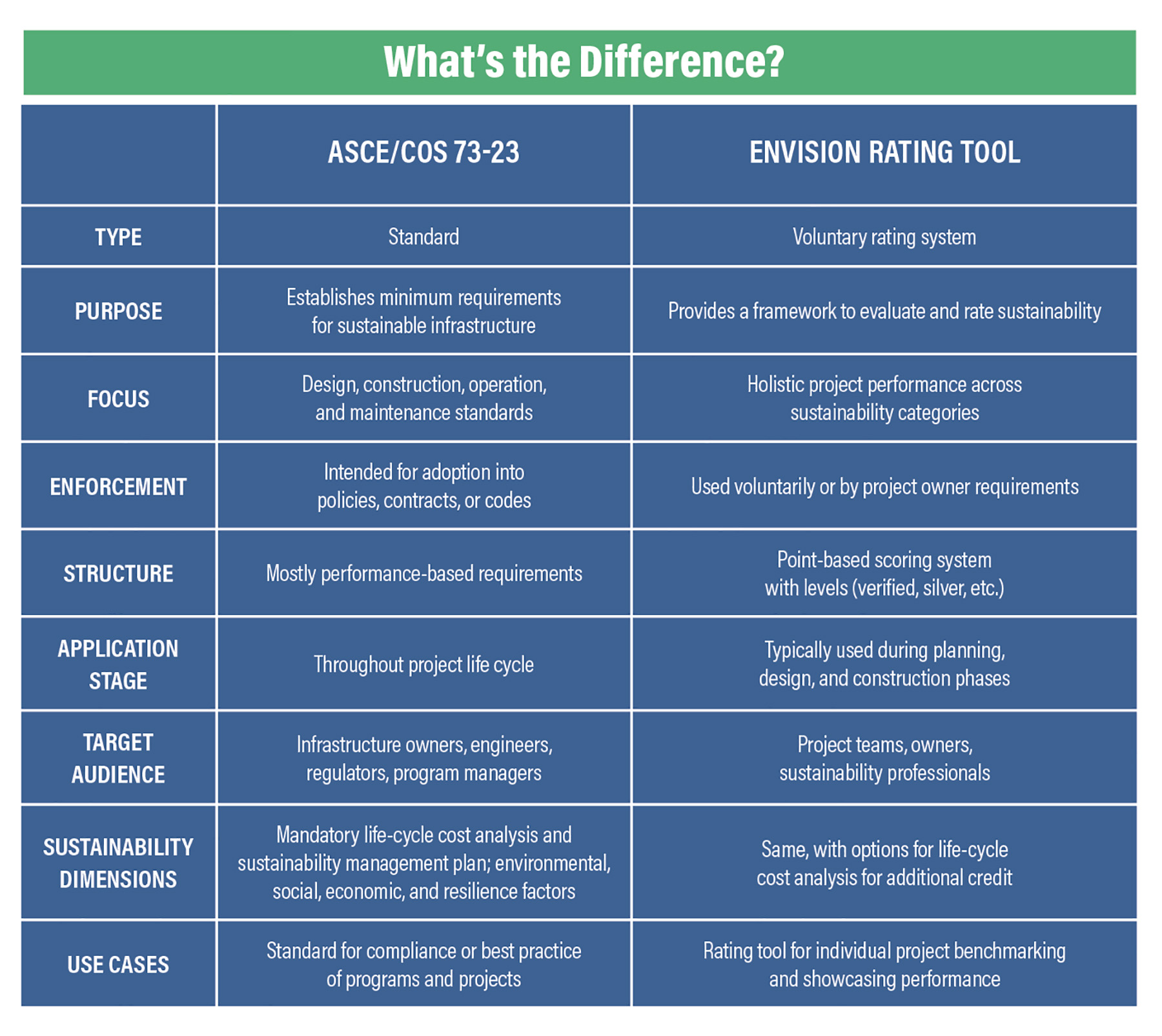

Envision is a voluntary tool that helps infrastructure owners, engineers, designers, architects, contractors, and others plan, design, and deliver more sustainable infrastructure projects. It uses a points-based system to evaluate projects across 64 sustainability and resilience indicators (or credits) in five categories: Quality of Life, Leadership, Resource Allocation, Natural World, and Climate & Resilience. Projects earn sustainability ratings, ranging from Verified to Platinum, based on the number of credits or points they earn.

The Envision approach is much like the U.S. Green Building Council’s widely used LEED system, but for infrastructure instead of buildings.

Notably, Envision includes a third-party verification process. Verified projects receive public recognition for demonstrating sustainability and resilience, including a plaque that owners can display on-site. They may also benefit from improved project performance, a competitive edge in bidding and funding, increased public trust, and stronger long-term outcomes.

Making a commitment

While Envision was a strong starting point for promoting sustainable infrastructure project development, it does not carry the same weight as an ASCE standard. ASCE’s standards are developed in accordance with the American National Standards Institute’s essential requirements, a rigorous process that includes broad stakeholder consensus as well as public comment and formal approvals. Even with the availability of Envision, the industry still lacked a formal standard to guide sustainable infrastructure development.

Seeing the need for such a standard, Jim Rispoli, P.E., Dist.M.ASCE, ASCE Sustainable Infrastructure Standard Committee chair, took over the effort to develop one in 2019. According to Mike Loose, P.E., Dist.M.ASCE, former chair of the ASCE Industry Leaders Council, Rispoli set out to develop the standard at “breakneck speed,” completing it in two years as opposed to the five years it typically takes.

Eager to meet this ambitious goal, Rispoli — who had previously served as an assistant secretary of energy under President George W. Bush — reached out to volunteers to join the SISC, a subcommittee of the Committee on Sustainability. In accordance with ANSI requirements, the committee had to be balanced among consumers, producers, and general contractors. One of those who answered the call was Loose, a retired vice admiral who knew Rispoli from their time in the Navy. Also part of the process were an environmental regulator, materials industry representatives, engineers, contractors, planners, and members of various economic development agencies.

Understanding the scope

Once people were in place, the committee got to work. Some members spent 25-40 hours a week on the effort, making it practically a full-time job as they aspired to meet Rispoli’s ambitious timeline, Loose says. But it was not just the accelerated schedule that made developing ASCE/COS 73-23 difficult; several unconventional aspects of the standard also posed challenges.

One of those components was the standard’s structure. According to Loose, most ASCE standards are prescriptive, meaning that they detail exactly how to do things. For instance, ASCE/SEI 59-22 Blast Protection of Buildings details the steps that building owners, developers, and consultants must take to achieve the minimum requirements in the event of an explosion.

In contrast, ASCE/COS 73-23 is largely performance based, focusing on the desired outcomes of the completed solution rather than prescribing exact processes, methods, and steps for achieving them. “That was very unusual,” Loose says. “Less than 5% of ASCE standards are performance based.”

Another distinct aspect was the broad scope. Unlike most ASCE standards, which focus on specific types of infrastructure or infrastructure components, ASCE/COS 73-23 had to apply across all types of infrastructure, from roads and bridges to dams, airports, and marine facilities.

Additionally, it had to consider the entire life-cycle cost of a project, rather than just the cost at completion. “We had to consider not only installation costs but also maintenance and operations costs over the infrastructure’s life (up to 100 years) to protect and professionally steward private and public funds,” Loose says.

Adding to the complexity, the committee aimed to make the standard mandatory for direct infrastructure owners, especially state and federal agencies, to develop sustainable projects. “Of the public sector people who were on our committee, they said, ‘If you do a guideline or a manual of practice, we look at it, but we basically ignore it. However, if you do a standard, we know it’s gone through the rigorous consensus-based ANSI process to make sure you got it right, so we’re likely to adhere to that,’” Neimeyer explains.

Developing the standard

With those parameters in mind, the committee crafted the standard. Recognizing that infrastructure professionals were already familiar with Envision, they decided to align the standard’s six chapters with Envision’s five categories. They structured the chapters — Sustainability Leadership, Quality of Life, Resource Allocation, Natural World, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Resilience — to connect Envision with the standard, allowing them to complement each other, Loose says.

From there, the committee developed the standard’s 29 outcomes, detailed in the chapters, to guide sustainable infrastructure development throughout the entire project life cycle. For example, the Quality of Life chapter includes an outcome focused on supporting community needs and goals through engagement early in the project. In the Greenhouse Gas Emissions chapter, one of the outcomes calls for the development of a greenhouse gas emissions reduction plan that decreases the project’s carbon dioxide equivalent by 15% from the baseline using one or more identified methods.

Next, the committee conducted internal beta tests and decided that projects did not need to meet every outcome to comply with the standard. Instead, they concluded that achieving 19 outcomes would be sufficient to be considered a sustainable solution. This flexibility provided leeway for projects with “not applicable” outcomes.

For solutions that meet at least 19 outcomes, teams must conduct a life-cycle cost analysis to determine the lowest life-cycle cost of all alternatives, and they must include a sustainability management plan to ensure a sustainable infrastructure solution. According to Loose, this ensures that the project is economically sustainable for decades, as outlined in ASCE’s triple bottom line for sustainability, the pillars of which are environmental sustainability, social sustainability, and economic sustainability.

Addressing public comments

Throughout the development process, the committee had to reach a consensus on what to include in the standard. Achieving this ANSI requirement was no simple task given that the committee included a broad spectrum of members with differing viewpoints. But after about two years of work, the members reached an agreement on the draft standard and secured approval from the full ASCE Codes and Standards Committee. The CSC moved forward on the next step of the ANSI process: a published notice to announce the public review of the proposed standard along with the dates for the public comment period.

During the public comment period, the proposed standard received hundreds of comments. Many commenters challenged whether the standard should be mandatory, arguing that it could not be mandatory because it allowed project teams to use engineering judgment to meet just 19 of the outcomes rather than all 29. They also objected to the standard’s use of passive language, including words like “should,” which gave teams flexibility in how to apply the standard.

Another point of contention was its greenhouse gas emissions chapter, which focused on both embodied and operational carbon. According to Loose, many of the industry commenters were concerned that the standard would negatively impact their specific industries due to the significant amounts of embodied carbon in their materials. “They said, ‘Hey, your proposed standard will hurt our competitiveness because someone could use timber construction, for example, which has minimal embodied carbon,’” Loose explains.

Getting approval

The SISC reviewed and responded to all the public comments. Several commenters later filed appeals, and the CSC found in their favor. Since the proposed standard allowed project teams to use engineering judgment to meet 19 of the 29 outcomes, the SISC decided to reclassify the standard from mandatory to non-mandatory. The CSC fully endorsed the SISC’s reclassification and the path forward to appropriately revise the title as well as portions of the front matter and two sections.

After reviewing the proposed changes, the CSC approved the revised standard for a second public comment period, which also generated about 100 comments. It reviewed and responded to all the comments, resulting in six appeals, many from the same individuals and groups who had objected previously. The CSC found in favor of three of the appellants.

After two years of back-and-forth with the appellants, to overcome the impasse, Loose, who chaired the SISC at the time, proposed a plan: The SISC would would invite and meet with the six appellants at a face-to-face meeting. The appellants would provide their proposed changes in writing, and they would be allocated time to discuss their change proposals. The SISC and the appellants would then engage in an open, robust, and collaborative discussion, with the goal being to achieve consensus on the modified language to the proposed standard, and then the change proposals and agreed-to modifications would be submitted for a SISC letter ballot for approval. If a third public comment period were required, authorization would be sought from the CSC. The CSC approved this approach.

The face-to-face meeting was extremely professional, candid, and productive, Loose says. The appellants’ proposed language modifications were presented and discussed. From there, the SISC and the appellants finalized language modifications to the standard, which was then letter balloted for approval.

The meeting concluded with all the appellants onboard and in agreement that a third public comment period was unnecessary. They then moved ahead with seeking CSC approval for the jointly revised proposed standard and subsequent publication of the standard.

The CSC gave its final approval and published the standard in 2023.

Spreading the word

Since the standard’s publication, the ASCE Committee on Sustainability and Society leaders have been actively promoting it to government agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command, the New York City Department of Design and Construction, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, encouraging them to use it for their programs. “Our senior leadership team is meeting with groups who own large pieces of infrastructure to discuss the application of the standard to their projects,” says Brian Parsons, managing director for the ASCE Environmental and Water Resources Institute and chief sustainability officer.

Neimeyer says he and others at ASCE recognize that it often takes time for large agencies to adopt these kinds of standards (the same was true for Envision). Still, they are hopeful it will be applied. “We haven’t had what I view as an early adopter yet, but that’s our mission moving forward ... to continue to push some of these big infrastructure owners to be an early adopter,” Neimeyer says. “I can say that any project that has gone through Envision has already used 90% of this standard because many of the principles — there are 29 in ASCE 73 compared to 64 in Envision — overlap.”

Sofia Zuberbühler-Yafar, RLA, assistant commissioner for sustainability and urban design with the NYC Department of Design and Construction, says that her team has been working toward encouraging their sponsor agencies to use the Envision framework on their capital planning processes — and she is eager for them to use the standard, as well. She appreciates that ASCE has developed the standard and believes the Society’s strong influence could encourage more infrastructure development teams to prioritize sustainable design. “The more (sustainability) tools that exist out there, the better,” she says.

That influence may soon grow, as a newly formed SISC is already at work on the next version of ASCE/COS 73. Established immediately after the standard took effect in 2023, the committee includes some of the original appellants from the previous public comment periods — voices that Neimeyer says will be critical as the group considers making the standard mandatory, which would be ideal. “Leading the civil engineering profession in sustainability is in our code of ethics, our mission statement, and our strategic plan. To achieve that, we need a standard that infrastructure owners and project teams will use.”

Jenny Jones is an award-winning freelance writer based in northern Virginia. She has more than 20 years of editorial experience and specializes in making complex subjects clear and engaging.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Civil Engineering.