By Leslie Nemo

The Marlette Lake Water System was one of the first in the U.S. to bring water over mountainous regions — all in the pursuit of precious metals.

In June 1859, silver was discovered on a property co-owned by Henry Comstock, a resident of what was then the Utah Territory, and it ignited 20 years of frenzied mining. What became known as the Comstock Lode is still seen as the largest deposit of silver ore discovered in North America. The construction of mines and related infrastructure for valuable metals, and the boomtowns that sprang up nearby, launched careers and sparked innovation. Samuel Clemens first tried out the name Mark Twain while writing for one of the local newspapers, for example, and a local company constructed the first water supply system in the world with an inverted siphon pipeline designed for pressures over 800 psi.

That network was the Marlette Lake Water System, which would bring water to several cities in what would become the Nevada Territory. Though the actual water body known as Marlette Lake was not part of the system until later, the first iteration of the pipe-and-flume infrastructure brought water from the Sierra Nevada mountain range at an elevation of 7,140 ft, down through a valley to a low of 5,143 ft, and rose again to 6,669 ft. “It was an engineering feat of no small magnitude to carry this enterprise to a successful completion,” wrote a contributor to Mining and Scientific Press a few months after the project was completed. “It will attract the attention of engineers all over the world.”

The potential riches in the Comstock Lode led to the founding of several towns, including Virginia City and Gold Hill. Virginia City’s population was about 2,300 in 1860. By 1880, it was nearly 11,000, while nearby Gold Hill was home to another 4,000 residents.

Those working in the two towns faced a major challenge: Water was never where they wanted it to be. Scalding waters from a geothermal aquifer flooded mines from below, making work difficult, but the flow of water needed above ground for residents and for ore milling operations could not keep up with the growing economy. Water companies sued for access to new streams, and some tried to give residents groundwater from the mine shafts, which prompted quality complaints.

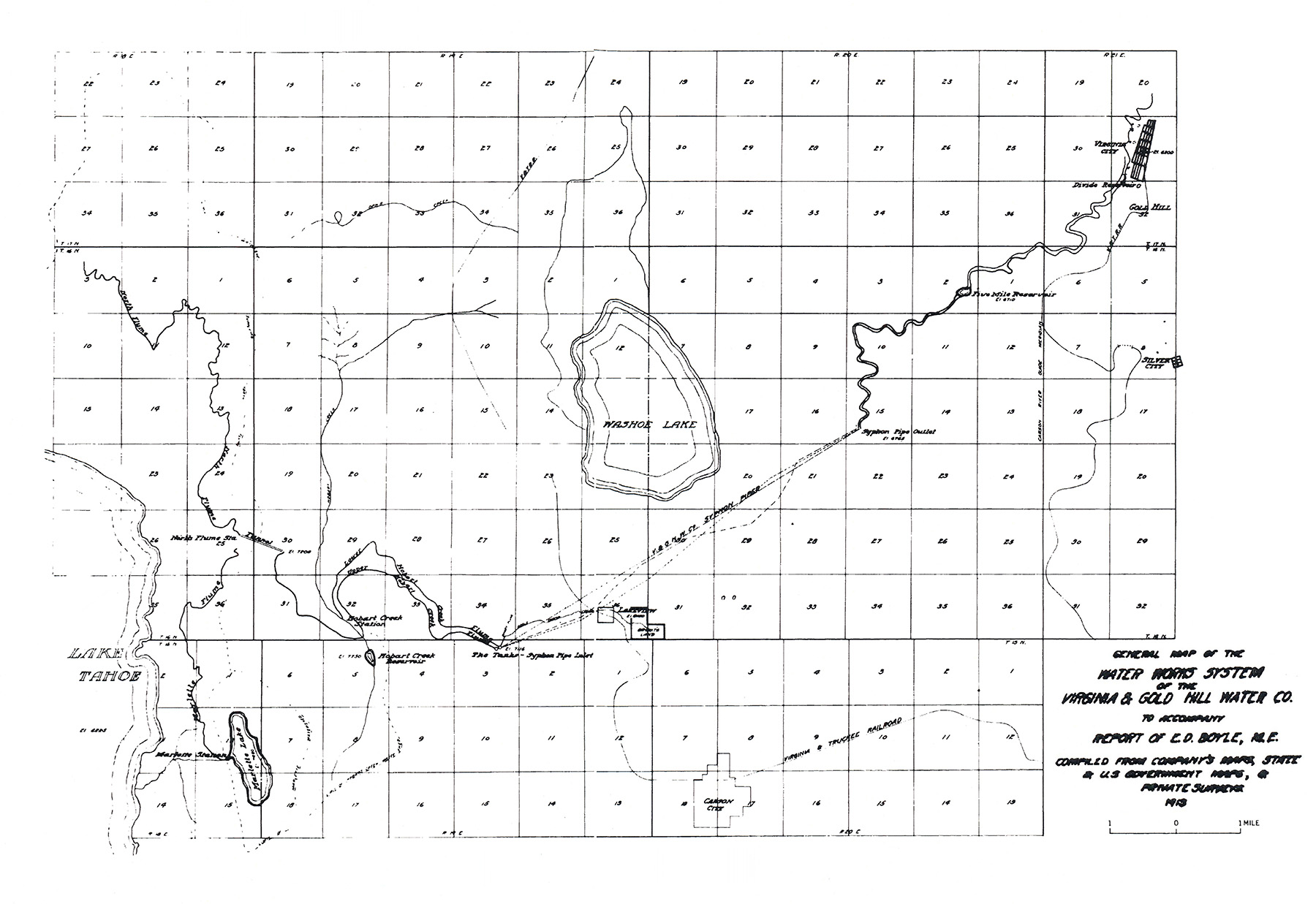

One of the businesses embroiled in lawsuits and offering residents dregs from the flooded mines was the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Co. As early as 1864, the company investigated sourcing water from the Sierra Nevada range. In July of that year, the company owners received a letter from a civil engineer named S. M. Buck who, at the company’s request, had surveyed the Washoe Valley and mapped a possible route for a pipe system to carry water from a distant lake into the towns.

The distance the water would have to travel (6 to 10 mi) — and the thickness of the pipes needed to handle the pressure — was so extreme that Buck did not bother to make a cost estimate, according to a letter he wrote cited in the paper “The Story of the Water Supply for the Comstock” by Hugh A. Shamberger. “It is an undertaking in which no prudent capitalist would ever invest his money,” wrote Buck (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper 779, 1972).

Dreams of transferring water from so far away were set aside until four local businessmen bought their way into the company. John W. Mackay, James G. Fair, James C. Flood, and William S. O’Brien, a group sometimes referred to as the “Bonanza Kings,” went into business together on a series of local mines.

It would be a few more years before the group discovered ore deposits that eventually made them some of the richest people in the nation, but in 1869 the group bought out another individual’s share in the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Co. By 1871, they were four of the seven company directors.

The year the Bonanza Kings became co-directors, the water company commissioned a second feasibility report from another engineer: Hermann Schussler. Born in Prussia, Schussler trained to be a civil engineer in Switzerland and Germany before moving to California in 1864. Up until the Bonanza Kings and their colleagues requested his help, he had spent most of his time in the United States working for the Spring Valley Water Works, the company that supplied San Francisco with water. Schussler had built a high-pressure water piping system to bring water down from Round Valley Lake into mines in California, and his experience led him to consulting work with water companies in other California municipalities such as San Jose and Oakland.

By the time the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Co. contacted Schussler, the 29-year-old “had more experience in high-head pipelines than any other civil engineer in the west at the time,” wrote Charles R. Spinks, P.E., M.ASCE, in the 2020 article “Water Supply to the Comstock, the Marlette Lake Water System” for the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress.

Schussler’s report, filed in October 1871, explained that he had followed the previously proposed route of a water pipe through the Washoe Valley. He thought the plan would work, except for about a mile of its length, he told the directors. “A few alterations in the route of the pipeline, so as to avoid short turns, rocky bluffs, etc., will make the line perfect.”

Though Schussler identified Marlette Lake as an eventual source of water for the two mining towns, he thought that any initial water system could draw what it needed from Dall Creek, later named Hobart Creek. If dammed appropriately, Schussler surmised that the waterway could form a reservoir holding 30 to 40 million gallons.

The cost of building the flume and pipe infrastructure to carry the water into Virginia City and Gold Hill would be about $100,000, he reported.

Schussler’s plans were received with skepticism by the Comstock Lode’s controllers, according to Eliot Lord, who wrote an account of the project construction in his 1883 book Comstock Mining and Miners. “Everything can be done nowadays,” Flood reportedly said. “The only question is — will it pay?”

The water company decided Flood’s question was worth trying to answer. On May 18, 1872, Schussler put in his orders for the pipe equipment. His design called for a wooden flume that would source water from Hobart Creek and another flume that would merge with pipe infrastructure already in Virginia City and Gold Hill. Between the flumes would be an inverted siphon running west to east across the valley.

The wrought iron for the inverted siphon was ordered from Scotland and shipped to the U.S. in sheets measuring 3 ft by 10 ft. Meanwhile, one San Francisco-based firm, George C. Johnson and Co., made the rivets. Another San Francisco operation, Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works, won the contract for rolling the wrought iron sheets, as it had experience making similar pipes for hydraulic mines in California.

How the pipes were rolled depended on where they would lie in the water system. At least a mile of the pipe was rolled in San Francisco. This stretch, Schussler explained in his 1871 report, would have to resist the heaviest pressure in the entire system. Here, the walls of the iron pipe were five-sixteenths of an inch thick.

Sections running 3 ft long, with an 11.5 in. internal diameter, were connected “using a 6-inch internal sleeve that was riveted to each pipe section with a single row of rivets to form pipe sections approximately 26 feet long,” per Spinks. After being rolled, each pipe section was plunged into heated baths of asphaltum and coal tar “between 7 and 15 minutes, depending on the thickness of the iron, until the pipe reached the temperature of the liquid to improve adhesion.”

Before putting the pipes intended for the high-pressure mile onto railcars bound for the project site, the company tested one section of pipe with its joint and found it could handle up to 1,400 lbs per square inch of pressure.

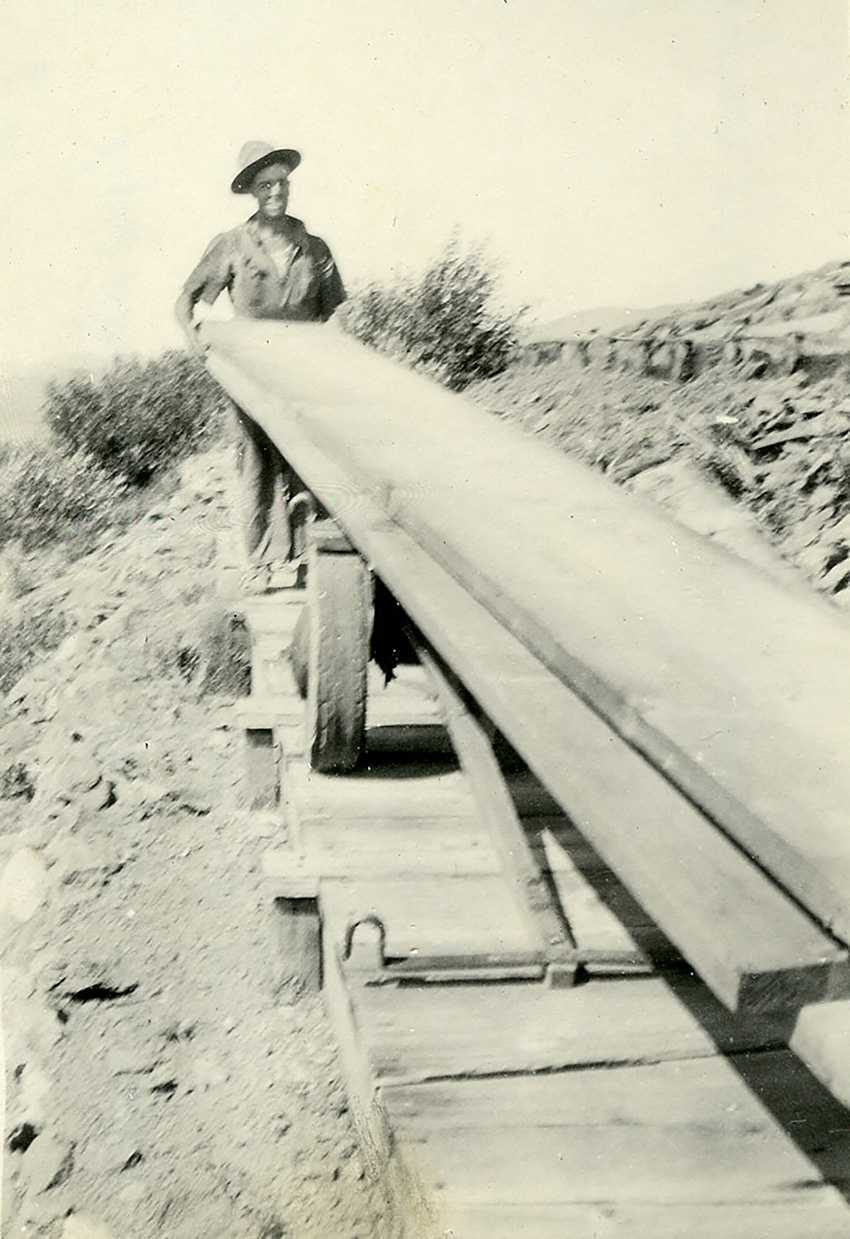

In Schussler’s report to the water company outlining how he would proceed with construction, he wrote that the thinner sheets of iron should be sent to Virginia City and Gold Hill to be made into pipes locally. Shamberger reported that Risdon Iron Works was given a diagram of the proposed route so that the pipe could be premade for its intended spot on the line. The end result was that the pipe segments matched the landscape exactly. They dipped, rose, or curved laterally to avoid tricky features like big rocks. Once the pipes were ready, workers and mule teams lowered them into ditches about 4 ft deep.

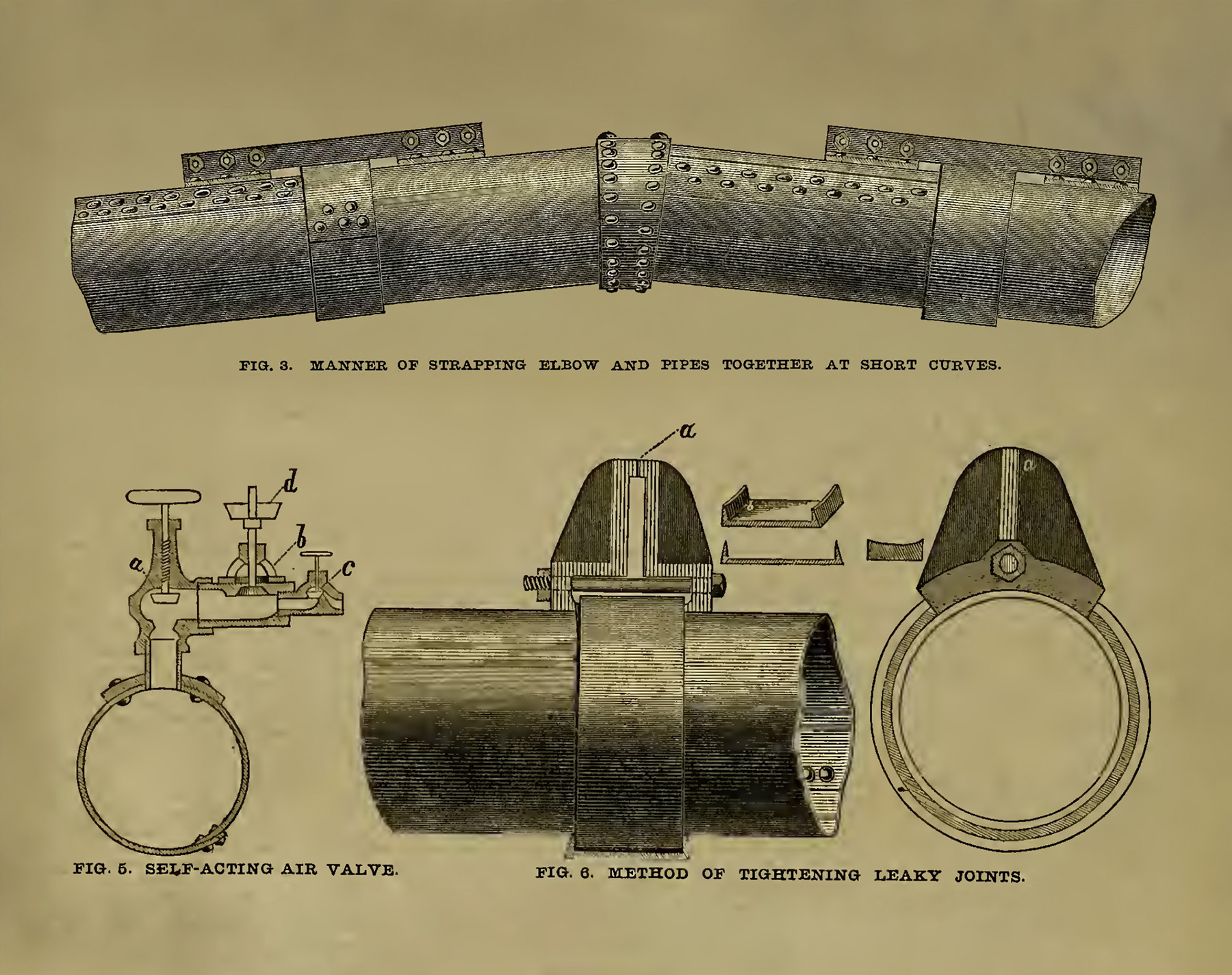

The entire pipe route had 16 low points, each equipped with a blow-off valve. At 14 high points, Schussler installed an air-vacuum valve for releasing any air in the supply, as well as a valve that could prevent vacuums from building in the pipes during any repairs.

Ultimately, laborers placed 700 tons of pipe equipped with about a million rivets into trenches along the route. Workers also built a diversion dam on Hobart Creek and connected it with the first wooden flume, which was 18 in. high and 20 in. wide. The flume ran about 4.6 mi along the mountainside before connecting with a tank that in turn connected to the iron pipe.

At the ends of the wrought iron inverted siphon, workers continued with a second wooden flume running just over 4 mi to a second storage site called Five-Mile Reservoir, and then one last wooden flume 5.6 mi into Gold Hill and Virginia City.

The first section of pipe was laid in the ground on June 11, 1873, and the last connection was secured between iron segments on July 25. Shamberger wrote: “The laying of 7 miles of 12-inch pipeline over very rough terrain in just 6 weeks was obviously a remarkable feat, keeping in mind that the motive power was men and mules.”

A minor weakness in the system was revealed when the water first flowed: The lead joints sitting roughly every 26 ft along the iron pipes were not staying put. Schussler had designed the joints to have an iron collar, 5 in. wide and a sixteenth of an inch thicker than the pipe it covered. A layer of lead went into a three-eighths inch gap between the collar and the surface of the pipe.

As the pipes expanded and contracted, they worked the lead out of position. When the water was first turned on and had been running for “some time,” two leaks “were discovered by Engineer Schussler and deeming it unsafe to continue the pressure again caused the water to be shut off for repairs to the pipe,” according to an account from the Virginia Evening Chronicle cited in Shamberger’s paper.

Captain John B. Overton, superintendent of the water company, implemented the solution: placing a wrought iron clamp over every collar that would push the lead back into place when tightened. Then a permanent bracket was added on top of the clamp. Overton found every blacksmith available to cast the clamps and get the pipe in working order, according to The History of Nevada by Sam P. Davis.

On August 1, the first flow of water reached Virginia City and Gold Hill at 6:45 in the evening, and its arrival was met with cannons and fireworks. With 2 million gallons a day flowing into the municipal water network, the Schussler system generated a dynamic pressure head at the pipe’s lowest point of about 1,900 ft, the highest in the world, according to Spinks. The next closest system — the one Schussler had designed to tap Round Valley Lake in California — was about half that pressure, according to Mining and Scientific Press.

Two more pipes would eventually join Schussler’s design and connect the boomtowns to Marlette Lake. The same year that the first inverted siphon started gushing water, the Bonanza Kings earned their nickname when a series of new ore deposits were found. The increased mining called for more water, so the company started construction on a second pipeline in 1875.

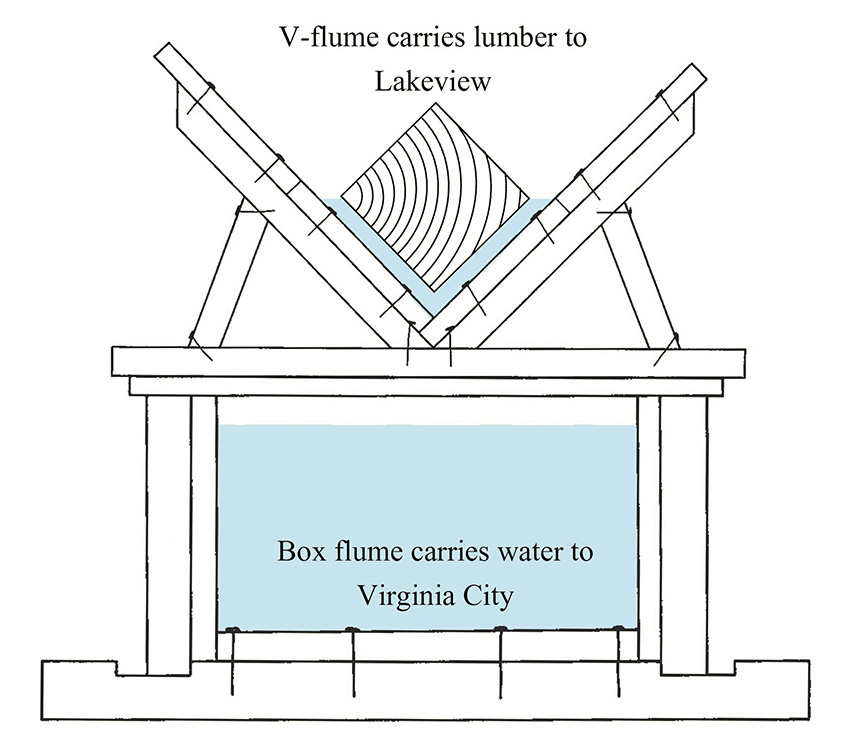

This version kept the wrought iron sections but ditched the lead joints. It sourced water from Marlette Lake after workers raised its earthfill dam to a height of 37 ft. It also incorporated a tunnel running 3,994 ft and carved part way through rock to help convey the lake water to the inverted siphon. This tunnel had two flumes: a box flume on the bottom for water and a V-shaped flume on top for lumber.

Besides the dam, this second system consisted of a 4.4 mi long wood flume 30 in. wide and 14 in. high that ran from Marlette Lake to the west portal of the tunnel and another 4.7 mi wood flume that ran from the tunnel’s east portal to a nearby creek. “A second tank was added at the terminus of the two flumes near the inlet to the pressure pipes,” according to Spinks. An extra 2.2 million gallons a day came to Comstock via this second water system when it started running in July 1877.

A decade later, the water company added a third pipeline (7.15 mi long and 11.5 in. in diameter) to the Lake Marlette system. Running parallel to the two earlier versions and with the same type of wrought iron sections, this construction effort added two more nuances. A new 8.3 mi long flume extended to Lake Tahoe tributary streams, and the pipes were considered a “converse lock-jointed type,” a design that had been patented in 1882.

Shamberger describes the joints this way: “On one end of each of the 21-foot sections were two knobs, the other end being fitted with a lock-joint sleeve with a layer of lead already in place. On assembling, the end with the two knobs was pushed into the lock joint and turned to secure ‘a lock.’ Lead was then poured in to make this a seal.”

Not long after the second water system was built, however, the mining boom that had fueled the growth of Virginia City and Gold Hill had started to bust. Silver production dropped off dramatically after 1878, and the populations of both communities decreased so much that Virginia City, the larger of the two, nearly became a ghost town.

Schussler had also moved on after the first inverted siphon he designed for the towns was under construction. During 1873, he served as chief engineer of the Sutro Tunnel Co., which built a nearly 4 mi long tunnel at the Comstock Lode to empty it of the hot water that had made mining difficult before the system came to be.

Today, a version of the Marlette Lake Water System serves Carson City and Storey County, the latter of which includes Virginia City. Visitors can tour the mines, mansions, and opera houses that gave the former boomtown its Wild West flair.

In 1975, the Marlette Lake Water System was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Leslie Nemo is a journalist based in Brooklyn, New York, who writes about science, culture, and the environment.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2026 issue of Civil Engineering as “High-Pressure Pipeline.”

To learn more about civil engineering history and ASCE’s Historic Civil Engineering Landmark Program, visit the Historic Landmarks page.