By Johann Zimmermann, P.E., and Joe Hochstetler, P.E.

After a significant flood, the damage sustained by major bridges usually gets the most attention. But what often gets overlooked is the damage done to small, privately owned bridges. Restoring these crossings quickly and sustainably is critical.

Changes in climate are driving more frequent and severe floods, which often means damage or destruction for small, local bridges. The victims of these storms often lose access to their communities, cutting them off from medical and social services, groceries, jobs, schools, fuel, and supplies. In some cases, they are compelled to abandon their homes.

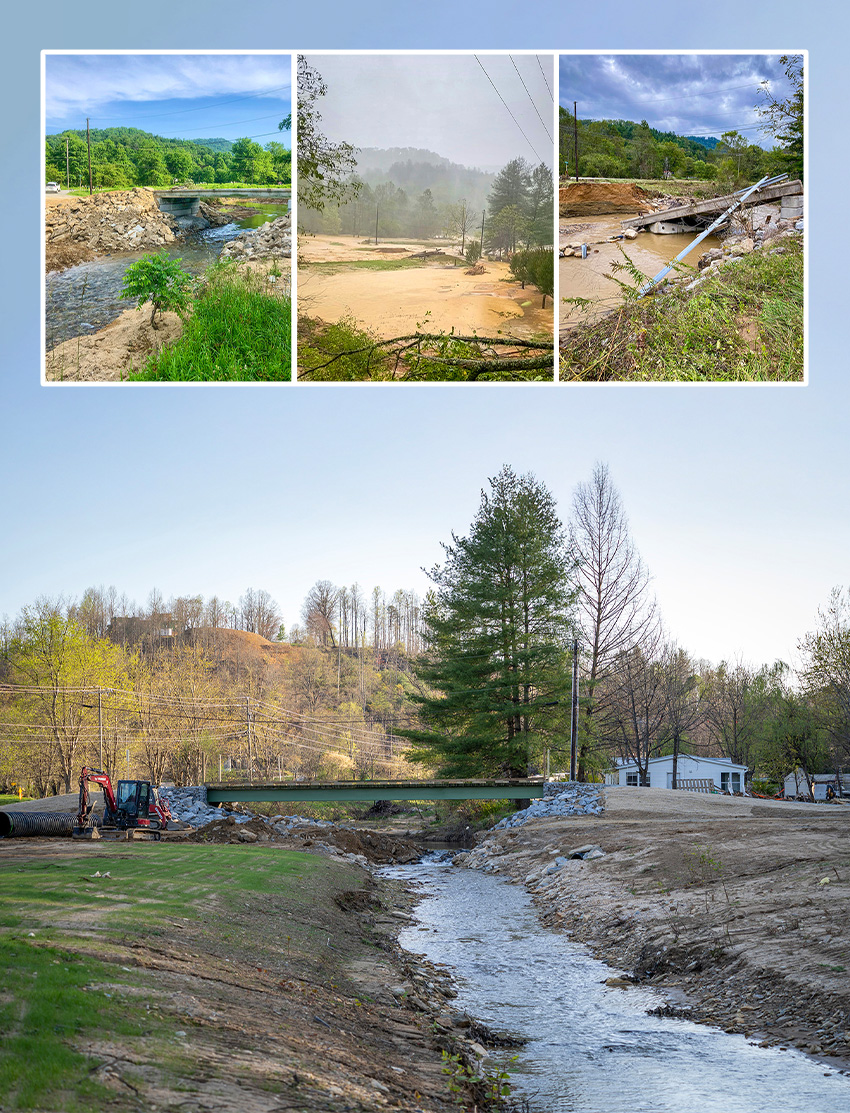

The North Carolina Department of Public Safety estimates that Hurricane Helene destroyed approximately 2,000 private bridges and culverts as it rampaged through Western North Carolina in September 2024. Since then, JZ Engineering — a structural engineering firm based in Harrisonburg, Virginia, that is focused on serving marginalized communities — has been busy designing and consulting with nonprofit agencies for the reconstruction of private bridges in this area.

The work in North Carolina in 2024 was based on experience with similar bridge washouts in other parts of the United States. In the aftermath of damaging floods in West Virginia in 2015, West Virginia Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster hired JZ Engineering to develop the West Virginia VOAD Bridge Project Guidelines. VOAD is a national organization with state and territory chapters that deliver volunteer services to communities affected by disaster.

The WV VOAD formed a committee to oversee the creation of these guidelines. The committee was made up of nonprofit organizations with input from human services agencies; emergency departments; Federal Emergency Management Agency officials; transportation officials; and local, state, and federal permitting officials.

Upon acceptance of the guidelines, Mennonite Disaster Service, a volunteer disaster response organization, and WV VOAD rebuilt 125 bridges in West Virginia. A similar process of developing guidelines was completed in other states, resulting in dozens of bridges built in southwest Virginia after a 2022 flood, in eastern Kentucky after a different flood in 2022, and in Vermont after Hurricane Beryl in 2024. The bridges were built economically, and their design was suitable for construction by crews of technically supervised volunteers. Some of these crossings have withstood numerous flooding events since being built, proving their resilience.

Most bridge engineers work on public infrastructure projects and are not familiar with the unique issues involved in the design and rebuilding of private water crossings. JZ’s experience with private bridge rebuilding has shown that the three most important issues are simplification of the permitting process, determination of the appropriate design criteria, and the construction of resilient abutments.

While the primary design criterion is resilience after a flood, crafting a design and construction plan that will be affordable for homeowners and buildable by supervised volunteer groups is also a major consideration.

Reasons for bridge destruction

In all these places, most of the destroyed water crossings were located on streams in rugged terrain or narrow valleys. The volume and velocity of floodwater caused severe scouring of the streambeds and banks, which in turn caused trees and vegetation to fall into the river, resulting in debris jams. In West Virginia and the surrounding Appalachia region, existing poorly built bridge superstructures, overtopped by floodwaters, were washed away, and abutments were undermined. Most of the replacement bridges are 30 to 40 ft in length.

In Vermont and western North Carolina, streams turned into wide rivers carrying stones and boulders. Altered streambeds required the average replacement bridge to be 60 ft long. In addition, some inadequately anchored bridge superstructures washed away due to the forces of the water and debris, but most of the destruction came from undermined abutments.

In all areas, most culverts were destroyed due to inadequate size, entrance and exit conditions that facilitated scour, and clogged rock, brush, and tree debris.

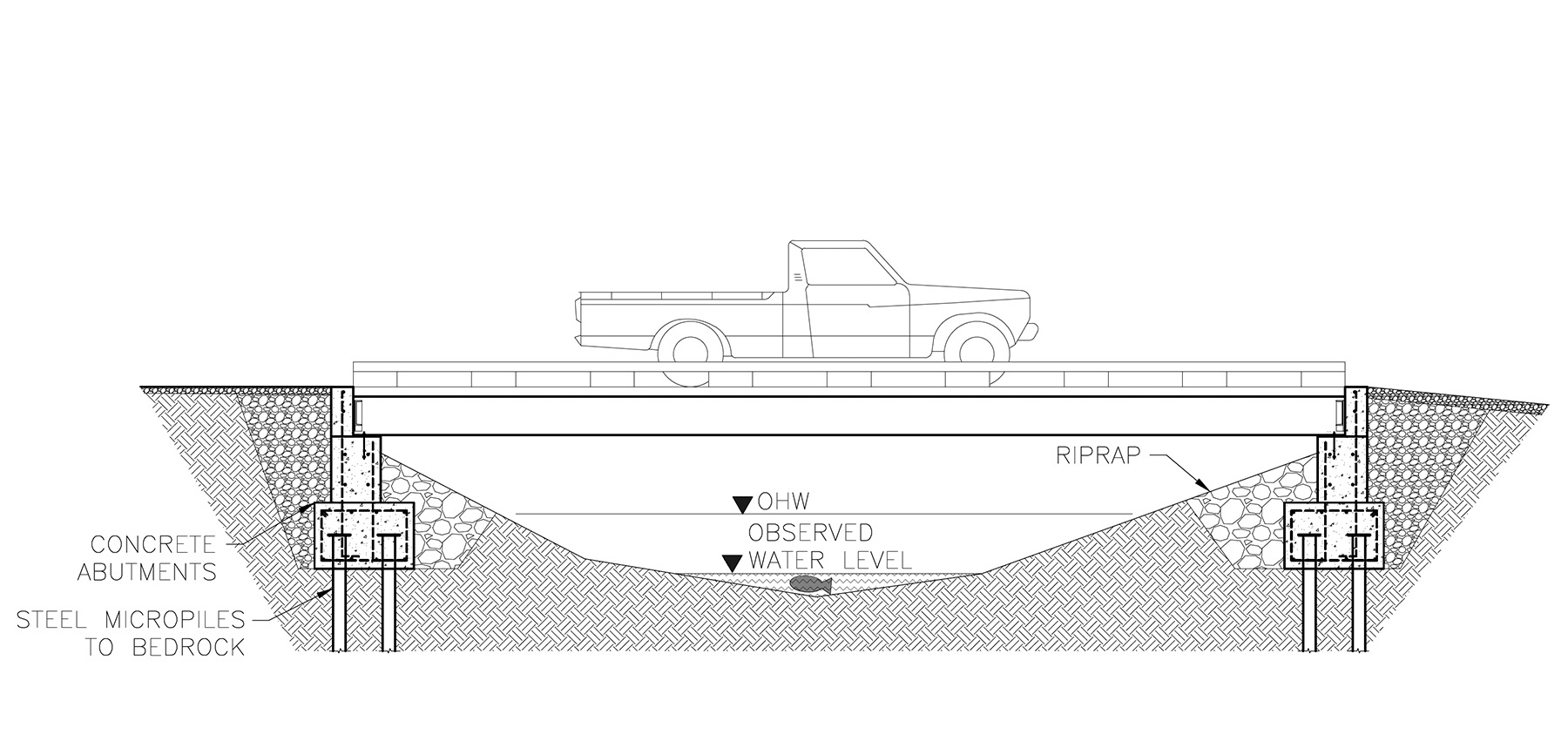

JZ estimates that more than 90% of the assessed private bridge failures resulted from abutment failure. Abutments were destroyed if they were built protruding into the stream channel, restricting the channel’s natural width and causing localized areas of scour. Most abutments had shallow foundations and were not supported on bedrock or by piles.

Bridge resilience

The intent of any bridge replacement should be to provide structures that are as resilient as possible given the limited economic resources available and the expected future flooding conditions. JZ developed the following principles for resilient private bridge construction:

- Bridge structures will span from bank to bank, with as much clearance above the floodwater elevation as possible.

- New abutments will be located outside the stream channel to avoid impeding the natural flow of the water and to minimize the likelihood of abutments being damaged by erosion and scour.

- Bridge abutments will bear directly on bedrock or on steel pipe micropiles driven to bedrock.

Bridge superstructures should ideally be rebuilt above the floodwater elevation, but at many sites, it may be topographically impractical to achieve this because the bridge location itself may be below the floodwater elevation. For example, the abutments of many private bridges are directly adjacent to a highway with minimal space available to ramp up to a higher elevation. Installing abutments outside the stream channel minimizes interference with the natural stream bed, restores the natural bank profile, and results in superior hydraulic conveyance versus the original, destroyed crossing.

Also, in most cases, spanning bank to bank will place the construction work above and outside the ordinary high-water level, which greatly simplifies permitting. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers typically will not require permits in these cases. Other permits that may still be required include county building or zoning, driveway/access, or stream/floodplain permits. In many post-disaster situations, if a bridge is replaced at the original location and demonstrates hydraulic conveyance equal to or greater than the original, a hydrologic and hydraulic analysis is not required, reducing the burden of reconstruction time and cost.

Design criteria

Because private bridges are not intended to carry the same high loads and volumes as highway bridges, their design and construction are not required to conform to the specifications of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials or the Federal Highway Administration. Building to AASHTO specifications would be cost prohibitive. Private bridges also do not fall under the International Building Code or ASCE’s Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures (7-22). Although private bridges are not required to meet these codes or standards, JZ’s guidelines were developed on the basis of information from these sources.

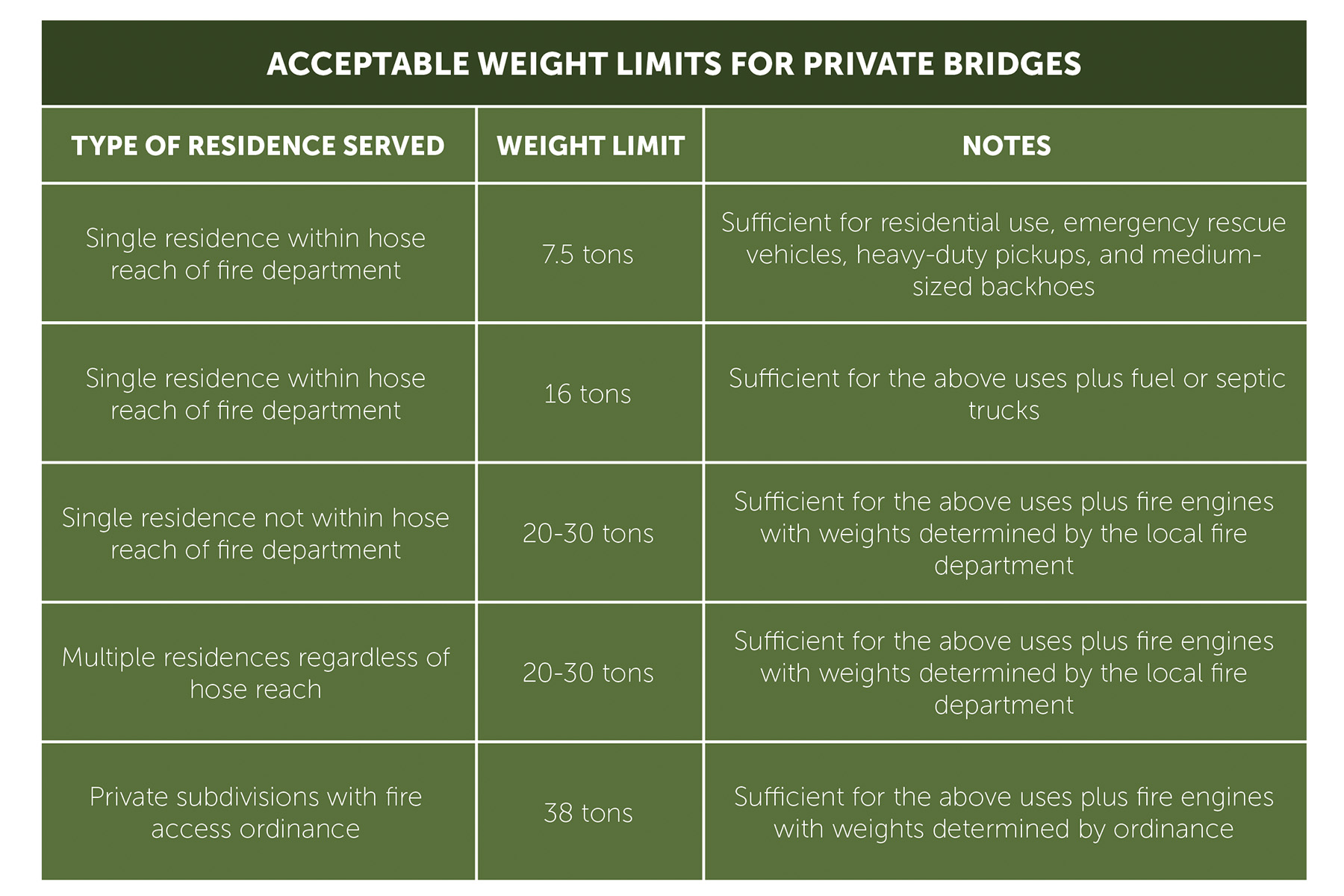

Vehicle loading criteria were devised with local emergency departments and building officials to accommodate the vehicles reasonably expected to cross the bridges. These private bridges are designed for single-lane, single-vehicle use. The generally accepted weight limits are shown below.

In many cases, deflection criteria control the size and therefore the cost of the bridge beams. Allowing a more liberal deflection than prescribed by AASHTO results in significant cost savings for low-volume, low-speed private bridges. For this reason, the deflection criteria from the IBC and the Transportation Structures Handbook (part 7709.56b of the U.S. Forest Service Handbook) were used.

Most bridges will be overtopped by floodwaters, subjecting the superstructure to pressure from the flowing water and drift buildup. In the absence of an expensive hydrologic and hydraulic study, the bridges are designed to withstand the transverse flood loads resulting from an average stream velocity of 10 fps as well as drift buildup against a square-edged superstructure. To prevent trapped air from causing uplift, the guidelines call for air release holes to be installed in the decks.

Abutments

Because abutment failure was the driving factor in more than 90% of the bridge failures JZ worked with, the bridge guidelines require all footings to be installed directly on bedrock or on steel pipe micropiles driven to resistance, which is usually on bedrock. Bedrock is typically not encountered above the water table. Because of the time and expense of dewatering a footing excavation, the bottom of the footing is usually installed just above the water table, and piles are driven to bedrock.

Conventional pile-driving equipment is too expensive for private bridges, and most light residential contractors do not have access to it. To solve this problem, JZ designed a driver head to economically install 4 in. diameter steel pipe micropiles.

Installation is performed with an excavator equipped with a 1,500 lb hydraulic breaker, using the driver bit between the breaker hammer bit and the steel pipe micropile.

Designing a footing supported by piles usually eliminates the need for a geotechnical investigation. The cost of driving steel pipe micropiles averages $3,000 per bridge, compared with more than $4,000 for a geotechnical study. And piles would likely be required, regardless.

Materials and methods

Bridges spanning from bank to bank result in longer bridge spans than those of the bridges being replaced. But this additional cost is offset by a savings: abutments that do not require large wing walls because they do not protrude into the stream channel.

Numerous types of superstructure options were considered, including cast-in-place or precast concrete, timber, and steel trusses. Culverts are used only for crossing small drainage ditches due to their potential to restrict the stream flow and to be destroyed by scour and erosion.

Steel W-shape beams most economically meet the design criteria for nearly all the bridges built to the guidelines.

Concrete, steel, and wood were considered as options for the bridge decking. Decks composed of nail-laminated, 2×4 or 2×6, vertically oriented, preservative-treated Southern Pine, use category UC4B under the American Wood Protection Association, can have a lifespan of more than 30 years. The speed of installation, together with the cost of materials, makes this a highly economical option suitable for volunteer builders.

Schedule and cost

The design of these bridges was developed with the input of more than 100 experienced construction workers, and the techniques are continuously being refined to improve quality and ease of construction. The construction time for a bridge under 40 ft long is generally six working days. Longer, single-span bridges, and those required to carry fire engines, may take two weeks to build. This tight schedule accommodates the limited time of the volunteers, reduces interruptions for residents, and minimizes rental costs for heavy equipment.

The average material cost for a 40 ft long bridge rated at 16 tons is about $55,000. The cost for a 60 ft long bridge designed to carry a 38-ton fire engine is around $90,000. Nonprofit groups providing volunteer labor add very little overhead. If the bridge is built by a contractor, the total cost can be expected to be two to three times the material cost.

Liability considerations

Many engineers feel hesitant to get involved in the design of private bridges in post-flood conditions with constrained budgets out of fear of liability issues. A trusting relationship between the engineer, the agency administering the relief, and the contractors or volunteers performing the work is required.

A hold harmless agreement is signed by the property owner and the entity performing or assisting with the construction of the bridge. This document makes it clear that the property owner assumes all liability for the bridge, holding harmless the entity performing or assisting in the construction, the bridge designer, subcontractors, and local government agencies and their employees. The agreement also assigns maintenance requirements to the owner.

Following these guidelines, JZ Engineering has designed more than 150 bridges that have been successfully built by volunteer agencies. Most importantly, an even greater number of families can sleep soundly when the next storm rolls in. More than 500 volunteers have had wonderful weeklong experiences and keep coming back for more.

SIDEBAR

Building a volunteer workforce

When a private crossing is destroyed, the effects can be devastating. Transportation and connection to community may be lost for months. But even a few days without this access is inconvenient at best and catastrophic at worst.

For the devastation caused by flooding in North Carolina due to Hurricane Helene, a volunteer workforce sprang into action. The Bridging Together initiative is a joint venture between Lutheran Disaster Response Carolinas and Mennonite Disaster Service, with most of the funding for construction provided by LDR and most of the volunteer labor provided by MDS.

Most volunteers who come through MDS are experienced or semi-skilled construction workers. Some are farmers who have construction experience, and they primarily work October through May due to their schedules. Construction teams consist of up to 10 workers. Typically, volunteers come as a group for a week, many driving up to 8 hours to the site.

Volunteers are managed by volunteer project directors experienced in construction. JZ Engineering consults with the director for each project and provides training workshops. To become a project director, a person must have built several bridges under the supervision of another project director. Project directors usually come for several bridges and return year after year.

The most difficult part of a bridge project is the construction layout of the bridge dimensions and angles across the stream, since anchor bolts need an accuracy that is within a quarter of an inch. JZ Engineering often performs the construction layout for the more difficult bridges, especially for ones with skewed abutments. Most volunteers are familiar with house construction, but concrete, steel, and bridge decking techniques may be something new to them. Minor mistakes sometimes occur, as in all construction projects, but the integrity of the design is always maintained.

In addition to the skilled volunteer groups, JZ Engineering has led half a dozen university engineering student construction teams through Engineers in Action — West Virginia Vehicular Bridge Program, which is a partnership between EIA, JZ Engineering, West Virginia Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster, and MDS.

Working with university student groups requires several construction workers with the patience and time to teach basic skills such as nailing, measuring, and using power tools, since many students have never been on a construction site before. This is valuable experience for engineering students, but the time to organize and prepare these groups is extensive.

No matter the skill level of the volunteers, their work is impactful, as they rebuild these damaged structures and restore life and health to these small, often rural communities.

For JZ Engineering, the collaboration with the contractors and volunteers has been and continues to be an exciting and rewarding endeavor. And JZ would be happy to share these guidelines with other engineers.

Johann Zimmermann, P.E., and Joe Hochstetler, P.E., are partners at JZ Engineering in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2026 issue of Civil Engineering as “Restoring Local Access.”