Upper Trinity Regional Water District

Upper Trinity Regional Water DistrictTo offset the ecological impacts of a new lake in Texas, more than 6 miles of streams have been restored.

The 7,600-acre Lake Ralph Hall on the North Sulphur River in southeast Fannin County will service one of the fastest growing areas in the United States: Denton County and part of Collin County in the Lone Star State.

Further reading:

- Highly engineered Mississippi River became author’s obsession

- Benefits flow quickly as historic dam removal restores Klamath River

- Seattle waterfront project restores beach habitat

As part of the construction project, expected to be completed in 2026, the Upper Trinity Regional Water District is building:

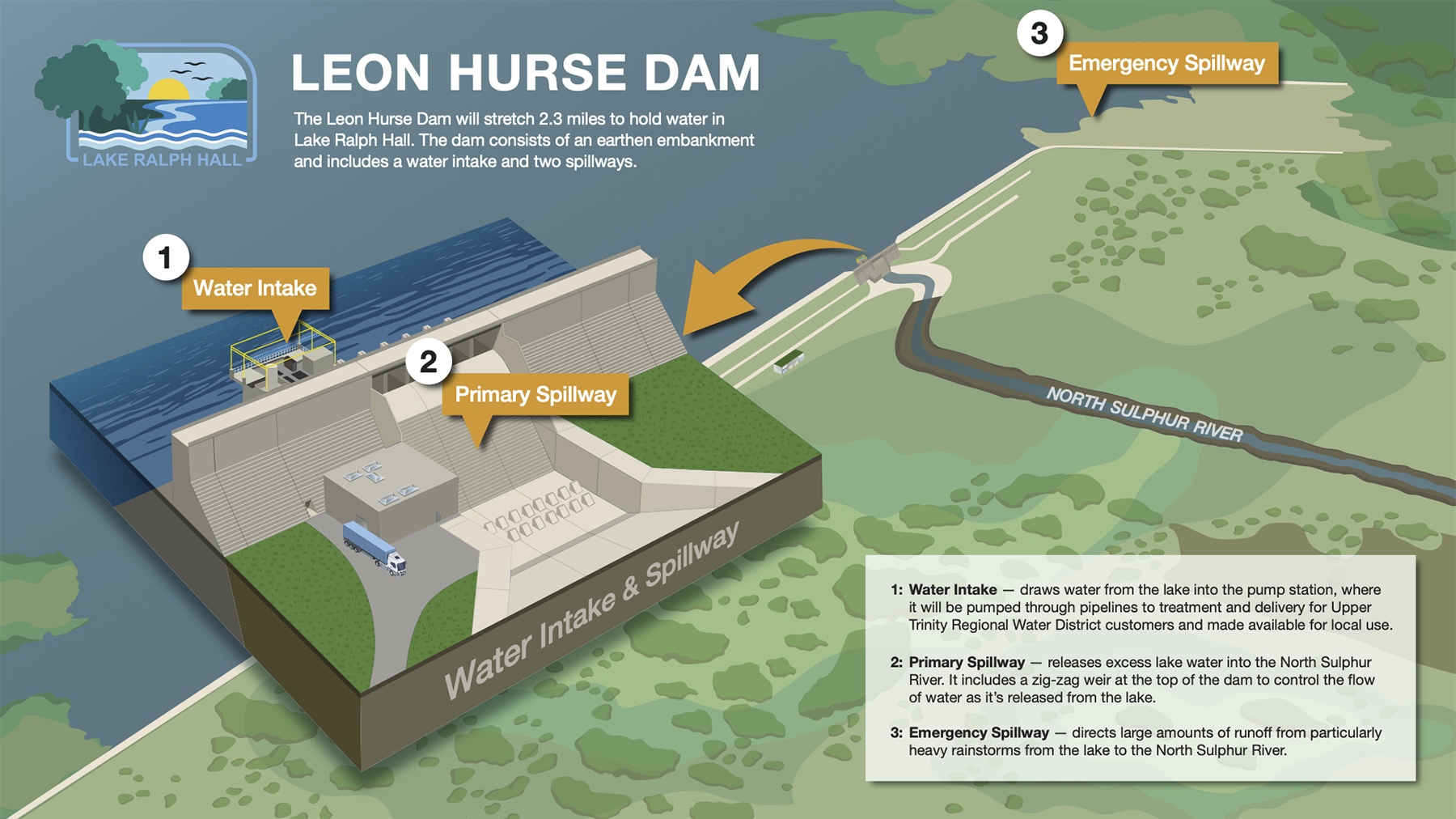

- The approximately 2.3-mile-long Leon Hurse Dam

- Spillways to release excess water back into the North Sulphur River

- An intake structure and pump station to move water to the balancing reservoir, where it can be pumped through pipelines to treatment. The station will initially be able to pump up to 45 million gallons per day and eventually up to 80 MGD.

The restored streams are below the future lake’s dam. In order to build the lake, the district had to get a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the restoration project was a necessary condition for the permit, explained Ed Motley, UTRWD project manager for Lake Ralph Hall.

Restoring the streams

A successful restoration project begins with a thorough understanding of the site’s hydrology and physical conditions, said Dustin Fitzgerald, site construction manager for Texas Mitigation Solutions, which assisted with the restoration project. This involves analyzing seasonal streamflow patterns, floodplain dynamics during high-water events, sediment transport and deposition, and baseflow conditions during dry periods. Hydrological modeling plays a key role in simulating different scenarios, helping inform a resilient design that considers future climate impacts.

Upper Trinity Regional Water District

Upper Trinity Regional Water District

The process usually involves a combination of engineering-, ecology-, and community-based efforts, Fitzgerald said. These include techniques like adding sinuosity, planting native vegetation, stabilizing streambanks, and creating floodplains. The goal is to enhance water quality, prevent further erosion, restore habitats, and reduce flooding while also addressing the project’s needs for water storage and supply.

Assembling a multidisciplinary team is equally important, Fitzgerald said. Civil and environmental engineers are essential for designing structural components, such as channel reshaping and erosion control, while ecologists and biologists ensure the project supports native vegetation and wildlife habitats. Regulatory experts help navigate environmental laws and permitting. Engaging these professionals early on ensures coordinated planning and successful implementation, Fitzgerald said.

The Lake Ralph Hall restoration

Keeping these principles in mind, the Lake Ralph Hall project restored the streams in what was once a severely degraded area. Cotton farmers couldn’t grow their crop because of frequent flooding from the North Sulphur River.

To improve cultivation conditions, the farmers created a 10-foot-deep and 16-foot-wide channel and forced the river to flow straight through. “As a result, the water in the river got progressively faster, and the swirling currents eroded the river bottom and banks,” Motley said.

“The channel was originally created to be 16-20 feet wide and 10 feet deep. Today, erosion has expanded the channel to over 350 feet wide and 60 feet deep in places. That’s well over 10 times its original size.” he added.

The Lake Ralph Hall restoration project began with a detailed assessment of the stream’s condition through site surveys, hydrologic modeling, and identification of a reference stream. The original stream, before human modifications (like straightening or channelizing), would have had a more meandering path with various bends, pools, and riffles (shallow, fast-moving water areas) as well as a much smaller cross-sectional area. In the past, the river likely had more of a natural curvature with tributaries that spread out across the land, interacting with the floodplain.

The result of extensive assessments, the restoration plan focused on restoring the stream’s natural path, reconnecting the floodplain, stabilizing banks, reestablishing vegetation, and enhancing habitat. The plan was developed in close collaboration with the Corps, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Construction involved excavating a new stream channel and floodplain. The team dug pathways for each tributary, incorporating bends to slow water flow and stabilize the banks. The streams’ sinuosity is as sharp as it is because its slope is extremely flat.

“One of the biggest challenges we faced was how easily the soil on-site washes away,” Fitzgerald said. “To help with that, we added erosion control structures – basically built-in reinforcements – at key points along the stream.

“We used natural materials like logs, tree branches, willow stakes, and rocks, so these structures blend in with the environment and keep the stream stable over time. This will help keep the channel from eventually washing out or cutting too deep.”

The team also spread temporary seed onto bare soil, Fitzgerald said.

Afterward, native trees and grasses were planted across the site. Biodegradable matting was laid along eroding or vulnerable streambanks to provide an immediate protective layer for the soil. It physically prevents soil from being washed away by water or wind and helps hold seeds in place while they germinate.

Native grasses are planted on streambanks and floodplains to establish vegetative cover. These plants are well suited to the local climate, soils, and hydrology, making them highly effective at stabilizing the land and improving ecological health. “This idea matches with the historical and natural landscape of this area of Texas,” Fitzgerald said.

Predictions for the future

When construction is complete, the streams will flow with initial rainfall. The stream system is designed to take the water from the contributing watershed, so there will be flow directly related to rainfall events, said Michelle P. Carte, regulatory and environmental compliance

coordinator at UTRWD.

Groundwater influence of the stream system may be a year or longer, depending on the amount of rainfall within the watershed once the stream system construction is completed. The streams will retain the water on the surface for longer periods of time, which will allow for groundwater recharge. As the groundwater levels increase, it will influence the flow of streams outside of rain events, Carte added.

Ongoing monitoring will track water quality, vegetation growth, erosion, and aquatic life health. Based on results, adaptive measures – such as replanting or additional stabilization – will ensure long-term ecological success and sustainability.