Brian Brenner, P.E., F.ASCE, is a professor of the practice at Tufts University and a principal engineer with Tighe & Bond in Westwood, Massachusetts. His collections of essays, Don’t Throw This Away!, Bridginess, and Too Much Information, published by ASCE Press, are available in the ASCE Library.

In his Civil Engineering Source series, More Water Under the Bridge, Brenner shares some thoughts each month about life as a civil engineer, considering bridge engineering from a unique, often comical point of view.

Improving data management and visualization methods have been accompanied by the decentralization of data. In the past, data access and management was more centralized and more curated. You couldn’t just Google or ChatGPT something. You had to look it up in a book, after you found the book, often at the library. Library books could be found by using something called a “card catalogue,” which was a file cabinet filled with cards identifying different books. These books were mostly edited before publication to meet certain peer-review standards. Encyclopedia Britannica didn’t just write itself, at least in those days.

Today, anyone with a computer or smartphone can almost instantly access most of the world’s knowledge. It is possible to develop increasingly realistic images and compile somewhat realistic reports on any topic. With the advent of artificial intelligence, future editions of the Britannica may actually write themselves.

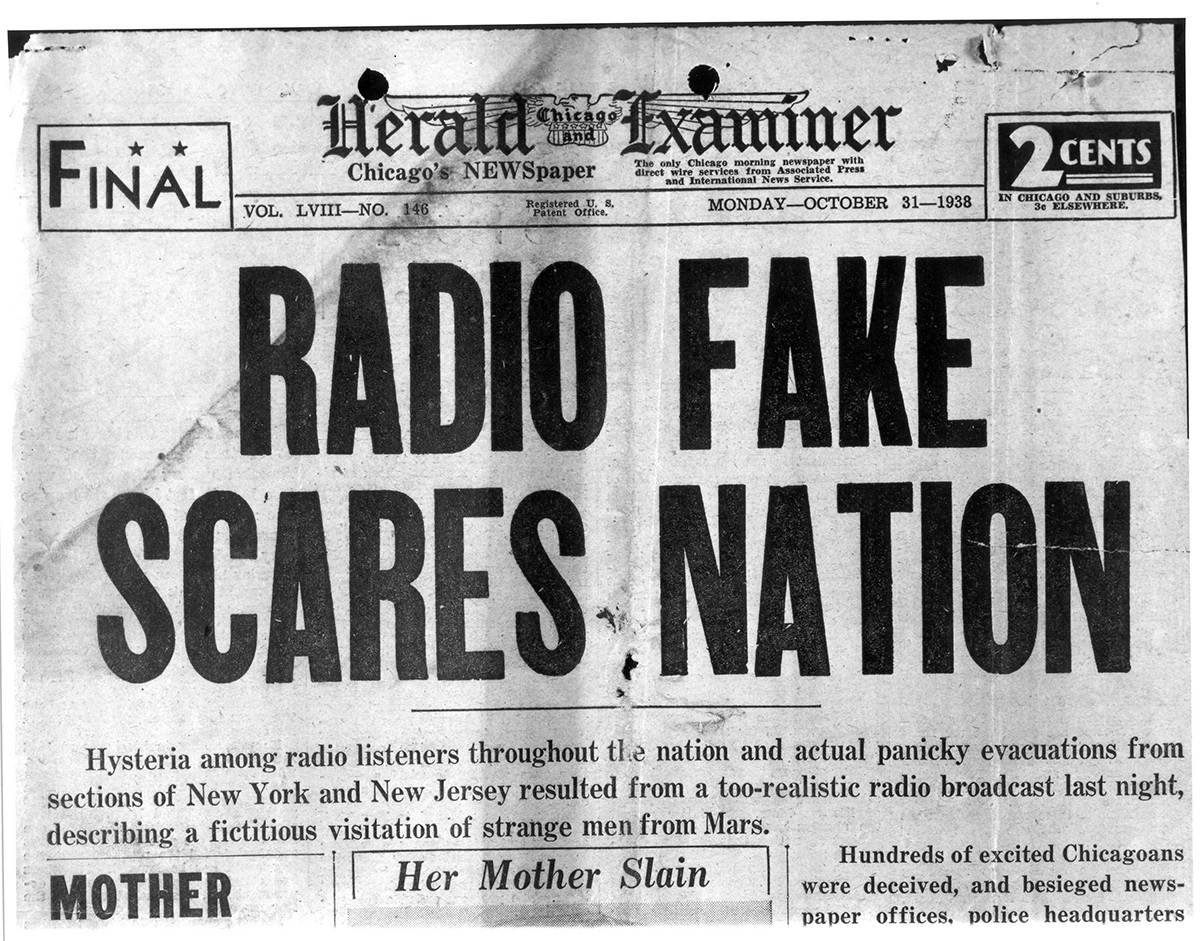

Back in 1938, there was a radio broadcast based on H.G. Wells’ novel, The War of the Worlds. The broadcast provided an account of an invasion by the Martians. The invasion was presented as a real event via a series of breaking news bulletins that interrupted a regular music program. These news flashes were a grim and realistic account of a developing Martian invasion told in real time.

Many listeners believed they were hearing a live account of an actual Martian invasion. Panic ensued. After frantic phone calls, the radio studio was ordered to interrupt the broadcast. At that moment in the program, the on-air announcer was reported to be choking on poisonous Martian gas. But fortunately, he recovered and alerted listeners that it was a simulation. There were no Martians.

The presentation and panic were achieved by a radio broadcast and the listeners’ imagination, with no graphics or videos. Since then, the War of the Worlds has been depicted in different media formats many times. In 2005, a film based on the novel was released. Fortunately, the movie was advertised as a drama and not a documentary. So there was no ensuing panic.

In the 2005 movie, the ex-wife of estranged husband, Tom Cruise, drops off their kids at his house in Bayonne, New Jersey. It was bad timing because on that day, the Martians attacked Earth. They launched probes that piled into the Bayonne city streetscape. The probes rose out of the earth to become giant three-legged, smoking tanks. After a pause, the Martians started firing ray guns that incinerated everything in their path.

Perhaps the film’s most dramatic scene was the demise of the Bayonne Bridge. The Martians trained their ray guns on the north approach spans. The steel plate girders, which were not designed for this load case, collapsed into piles of rubble. Panic ensued (on film).

Jim Henderson

Jim Henderson The Bayonne Bridge connects Staten Island, New York, to Bayonne, New Jersey, crossing the Kill Van Kull waterway. It opened in 1931, a few years before the Martians attacked on the radio program. It was the longest spanning arch bridge at the time. The span was long but not high enough to provide passage for present-day tall container ships unloading at the port on Newark Bay. In 2019, an innovative project to raise the deck by 60 feet was completed. This work featured complex construction staging. Traffic was maintained on the old span while the new span was built above it.

We know now, if we didn’t before, that the Martians did not attack in 2005. One way we can determine this is by considering the type of bridge shown to be destroyed in the movie. The movie showed the original version of the Bayonne Bridge, not the revised span. The filmmakers could not envision the infrastructure changing so dramatically. So it appears they showed the wrong bridge, and this is one way we know that there was no Martian attack.

The War of the Worlds began as an 18th-century novel by H.G. Wells, followed by a 20th-century radio broadcast, and then by an early 21st-century movie. Supported by advancing technology, the film showed seemingly realistic destruction of infrastructure, with bridge plate girders pulverized and large trucks flying through the Bayonne sky. Up until this point, the technology used was centralized. The 2005 version really (and sadly) looked like the Martians were destroying the Bayonne Bridge. But it took a large team of engineers and artists a long time and a lot of effort to create this scene and others in the movie.

Now that the distant future of 2025 has arrived, we have more decentralized access to data technology and the availability of generative artificial intelligence. Individuals can access, manage, and visualize data in ways that used to require rooms full of people.

Arnold Reinhold

Arnold Reinhold

Jim Henderson

Jim Henderson I wondered what ChatGPT thought about these technological developments, from a bridge perspective, of course. I asked:

ChatGPT, in the 2005 remake film of The War of the Worlds, the Martians destroy the Bayonne Bridge in New Jersey. In your opinion, was this scene realistic? What are some bridge engineering issues associated with the Martians’ attack?

Within five seconds, ChatGPT provided this response:

Great question! Let’s break this down like a structural/engineering critique of a Hollywood destruction scene.

Scene Context (2005 “War of the Worlds”)

In Steven Spielberg’s film, Martian tripod machines emerge from underground and attack New Jersey infrastructure, including the Bayonne Bridge—a massive steel arch bridge connecting Bayonne, NJ, and Staten Island, NY. In the movie, the bridge collapses quickly under attack.

Realism Assessment

1. Martian Weaponry Is a Wild Card

- The Martians use disintegration/heat-ray weapons—a fictional technology far beyond real-world explosives.

- If we assume their ray can instantly vaporize steel, then yes, total bridge collapse could happen quickly.

- But from an engineering realism perspective, the bridge wouldn’t fail so fast with ordinary explosives or thermal weapons—these structures are highly redundant and heat-resistant.

2. Structural Redundancy

- The Bayonne Bridge is a through-arch steel structure with built-in redundancy; damage to a few members wouldn’t immediately bring the entire span down.

- Hollywood often shows bridges collapsing completely for dramatic effect, but in reality, you’d likely see localized failure first, with parts sagging or deforming rather than instant total collapse.

3. Thermal Response

- Steel loses about 50% of its strength at ~1,100°F (600°C), and collapses become likely at higher temps.

- An intense Martian heat ray could conceivably heat members rapidly, but heating an entire 1,675-ft span evenly enough for full collapse in seconds would be unrealistic without sci-fi tech.

4. Connection Detailing

- Bridges like this rely on riveted/bolted gusset plates. Targeted destruction of a key pin or gusset plate at the arch springings or crown could destabilize the span—but even then, progressive collapse takes time, not instantaneous crumbling.

Bridge Engineering Issues to Consider

If we analyze it as engineers (ignoring Martian magic):

Redundancy & Load Path: Arch bridges are statically determinate but well-braced; knocking out a single member doesn’t always cause total collapse.

Thermal Expansion & Weakening: High heat causes steel to soften, expand, and lose stiffness. Severe, localized heating could cause buckling in compression members.

Dynamic Loading: Weapons or explosions could create shock waves, exceeding fatigue limits and causing brittle fracture in older steel.

Progressive Collapse Potential: Once one section buckles, loads redistribute; failure can cascade, but timing isn’t cinematic.

Age & Maintenance: The Bayonne Bridge (opened in 1931) was older and less ductile than modern bridges, which could accelerate collapse under extreme attack.

Foundations: Piers founded in bedrock; alien weapons would need extraordinary energy to undermine supports quickly.

Verdict

- Realistic if you accept Martian superweapons. With a sci-fi death ray, anything is possible.

- Not realistic if you assume earthly physics. Destroying the Bayonne Bridge with even advanced conventional weapons would take planning, sustained attack, and structural targeting—not a single flashy blast.

***

In addition to ChatGPT’s introduction (to me at least) of the new field of structural engineering critiques of Hollywood movies, there is a lot more to unpack. I’ll narrow this down to a focus on engineering education issues.

Generative artificial intelligence works by… I have no idea how it works, and that is after colleagues have tried to explain it to me a few times. Broadly, it seems to be able to quickly assemble information based on its training of volumes of data, and present organized, formatted responses to questions using a seemingly human writing approach. What it apparently cannot do, at least not well at this point, is evaluate, weigh data, and speculate beyond the possibly limited data it has access to in its training. Unlike Google searches, responses from an AI chatbot are not lists of references, but can be mini-papers or reports that look like they were written by people. But they aren’t, and understanding the limitations of the approach is important to successfully using it.

AI can assemble and report on existing information fairly well. The process of assembling and reporting on information is also a significant part of engineering education. Civil engineering disciplines all involve researching, evaluating, and presenting constitutive information. By doing so, students also learn the meaning and theory of various analysis and design approaches. This is essential to gaining expertise, and it is baked into the traditional engineering education process.

But if students can ask ChatGPT to do homework and other tasks, they may not be engaging in the process of learning that needs to be learned. Ironically, ChatGPT and other AI tools are potentially very useful in engineering work. But engineers can use these tools effectively only if they are experienced in the various processes, theories, and components of what they are analyzing and designing. Without this experience, they have a limited ability to review and judge the appropriateness of AI responses. Sometimes AI can “hallucinate” based on faulty information that it was trained on.

It is a Catch-22 situation: to benefit from AI data management/reporting capabilities, you need to have a high-level understanding of the topic you are evaluating. But if you use AI before gaining this expertise, you may circumvent the process of becoming experienced in the first place.

What is implied is the need to rethink traditional engineering teaching methods so that rising engineers can be equipped to use and benefit from generative AI while still mastering the basics. Engineering teaching methods have been in place for decades. Revising them is not a trivial job. That is one challenge posed by generative artificial intelligence.

There are other challenges.