The Muziekcentrum De Bijloke is a concert hall located in a former medieval hospital in Ghent, Belgium. Originally constructed in the 13th century to provide medical care for travelers and the poor, the masonry structure with an elaborately detailed wooden roof has been used as a music venue since 1988. But the site suffered from poor acoustics because of its shape, says Ned Crowe, CEng, an associate acoustic consultant in the London office of the international engineering firm Arup. Other factors also contributed to a “real lack of intimacy” for the audience in terms of the concert experience, he notes.

Arup was responsible for the acoustical design of a major renovation to the Bijloke concert hall that was completed late last year.ABT Belgium, based in Antwerp, Belgium, was the structural engineer for the project, which was designed by London-based DRDH Architects.

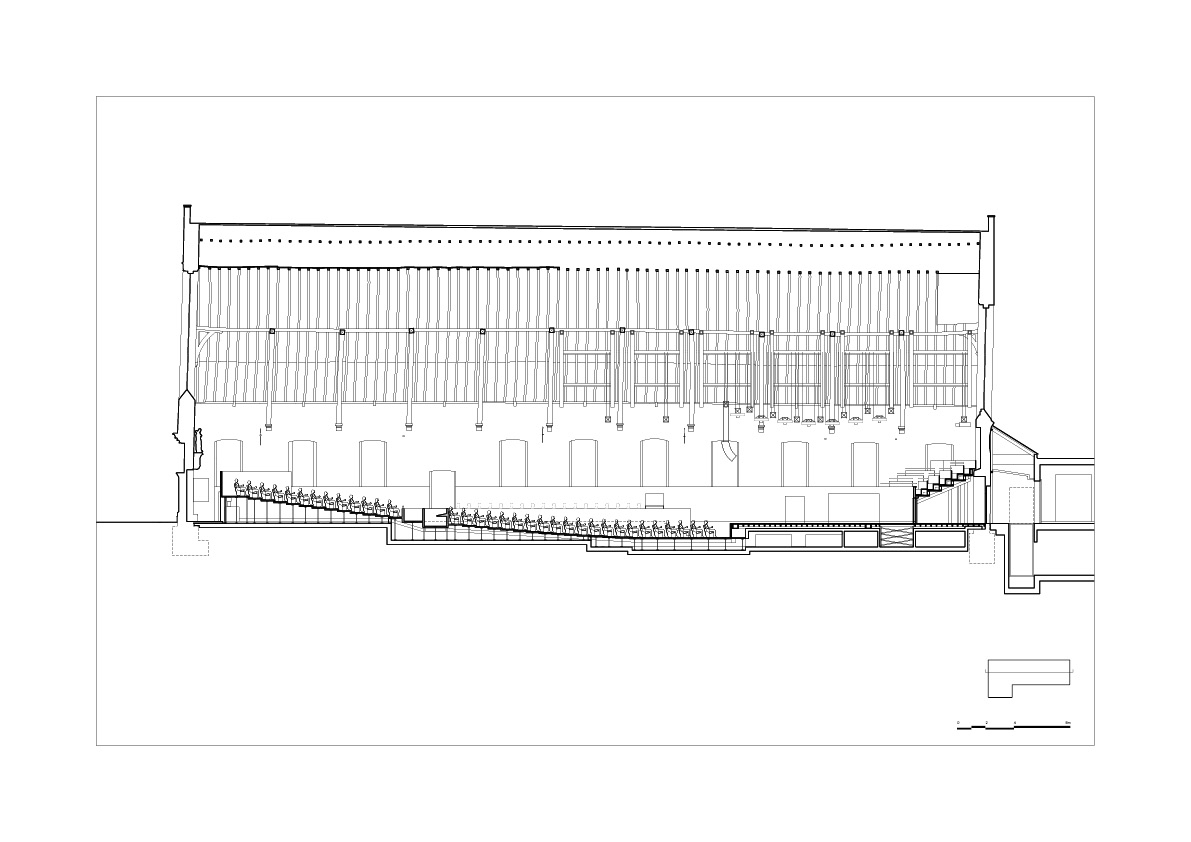

The structure measures 55 m long by 15 m wide, which created a venue with less-than-ideal proportions for a concert space, says Crowe. The hall was “particularly long in comparison to its width,” he explains, especially because “the orchestra platform was right up against the upstage wall and the seating went right to the back at the other end — that was the geometric issue.”

Other concerns involved the side walls of the hall, which over the centuries had begun to lean outward because of the forces imposed by the roof, says Charlotte Franck, an engineer and architect at ABT. Although the walls of the hall were not in danger of collapsing, the outward lean did negatively affect the acoustics. “We want the audience to feel completely surrounded by the sound, immersed in the sound,” Crowe says. “And a good way to achieve that is to have strong reflections from the side walls” of the concert space. But when the sound from the orchestra hit the sloping side walls in the Bijloke hall, “instead of reflecting back to the audience, the sound just got sent upward, so the audience got no benefit from those side reflections,” explains Crowe. As a result, the sound seemed to come only from in front, rather than enveloping the audience, Crowe says.

Sound ideas

The natural reverberance of the site was also inadequate, Crowe says. Reverberance refers to the depth and resonance of the sound, which is controlled by the volume of the space and the amount of sound-absorbing material. In the Bijloke hall, the natural reverberance was “acoustically rather dry,” Crowe says, and the large surface area of the roof timbers was full of cracks and fissures that captured sound. Plus, there were various sound-absorbing finishes throughout the space, including the drapes, the carpeting, the chairs, and other materials. To enhance the reverberation, the music center’s staff had previously installed an electro-acoustic system of microphones and loudspeakers, but that system was getting old and in need of replacement, Crowe adds.

To address these various challenges, the architects and engineers made a number of changes to the site, some subtle, some much more dramatic. The most significant alteration involved lowering the floor of the hall by 1.2 m in order to increase the overall volume of the space, says Crowe. This was accomplished by removing the seats, balcony, and stage of the interior and demolishing the original floor and the plenum space beneath it. During this work, a series of concrete piles were installed to reinforce the existing brick foundation, says Franck. Because of the site’s historical significance, an archeologist supervised the excavation work, Franck adds, and a drainage system was installed to accommodate the site’s high water table.

‘Timber boat’

After a new concrete floor was placed, concrete columns were installed above the floor to support a series of brick walls, clad with wood, that now line the interior of the concert hall. Forming “a sort of timber boat” within the existing structure, the roughly 2.5 m tall walls provide the sound reflection for an immersive audial experience that the tilting masonry walls could not, Crowe says. Under the historical preservation rules that governed the project, the new walls could not be connected to the original masonry walls. But the masonry walls, which turned out to be hollow, could be locally filled in with concrete and mortar to help support the new steel structure that was installed within the hall’s timber roof, explains Franck.

The steel structure supports new lighting and other equipment as well as an array of sound-reflecting timber panels that help the various sections of the orchestra hear each other, says Crowe. A new steel system was necessary because the historical roof structure — which reaches its apex 22 m above the floor — could not support additional loads. The system features a series of steel bowstring trusses and more than 200 steel cables that are painted black and essentially follow the shape of the wooden elements in the roof, making the new steelwork practically invisible, Franck says.

A new concrete-framed stage, topped by a wooden floor, creates an improved acoustical mass. The new stage is also low enough that large musical equipment can more easily be brought on and off without the use of a lift, as had previously been required, Crowe says. The stage was also moved forward into the hall by about 5 m, which improves the concert experience for those in the farthest back seats and also creates space for new choir seating behind the stage. The choir seating involves wooden benches with removable cushions rather than individual chairs; when a choir is not present, the sound-absorbing cushions can also be removed so that the benches help reflect sound.

Elsewhere in the hall, the sound-absorbing drapes and carpeting were removed, and the new audience chairs were designed with wooden backs and armrests. The only soft material is on the seat itself for improved acoustical performance, Crowe notes. Overall, the number of seats in front of the stage was reduced from 975 in the original hall to 720, plus seating behind the stage for another 110 choir or additional audience members.

Acoustical analysis

The process of an acoustical renovation generally begins with a careful examination of the site that includes listening to a musical performance, taking detailed sound measurements, generating a digital acoustical model of the existing hall, and then tweaking and calibrating those efforts as the design develops, Crowe explains. This process is normally repeated after the work has been completed to ensure that the new acoustics are an improvement. But the travel and performance restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has made such follow-up work nearly impossible.

The Bijloke music center opened last year for rehearsals and a few performances with limited audiences, but more recently the site has offered only livestreamed concerts. Arup’s team held some online discussions with the client and the orchestra members, and the feedback was positive, Crowe says, but the team looks forward to someday revisiting the site in person to confirm the new acoustics.