Wondering what to do with those millions and millions of disposable face masks that people have been wearing during the pandemic — and then disposing of basically wherever they please?

Why not make a new road?

That is what researchers at RMIT University, in Melbourne, Australia, suggest. They have been experimenting with how to recycle single-use, disposable face masks into road pavement material. Their research indicates that when shredded face masks are combined with processed building rubble, the resulting material can be used as the base layers of roads and pavements. In fact, the shredded face masks actually help “build better and stronger roads,” says Jie Li, Ph.D., an assistant associate dean and professor of civil and infrastructure engineering in RMIT’s school of engineering.

“The face masks have some amazing properties, including high tensile strengths and ductility,” Li explains. As a result, the masks “could provide higher strength and stiffness and more flexibility to the base and subbase of roads.” In addition to these engineering benefits, Li adds, “the other benefit would be reducing the challenging environmental issue of face masks.”

Li explains that the COVID-19 pandemic “has created not only a global health and financial crisis but also an unprecedented impact on the environment. We can see the masks littered or blown up into the parks and streets or blown into gutters and washing down the drain, impacting our waterways and wildlife. Since disposable face masks are mainly made of nonbiodegradable plastics, these single-use masks will take as long as 450 years to break down in the environment.”

But if the face masks are recycled into road-building material, a single kilometer of a two-lane road would consume approximately 3 million masks, preventing 93 metric tons of waste from going to a landfill, the RMIT research indicates.

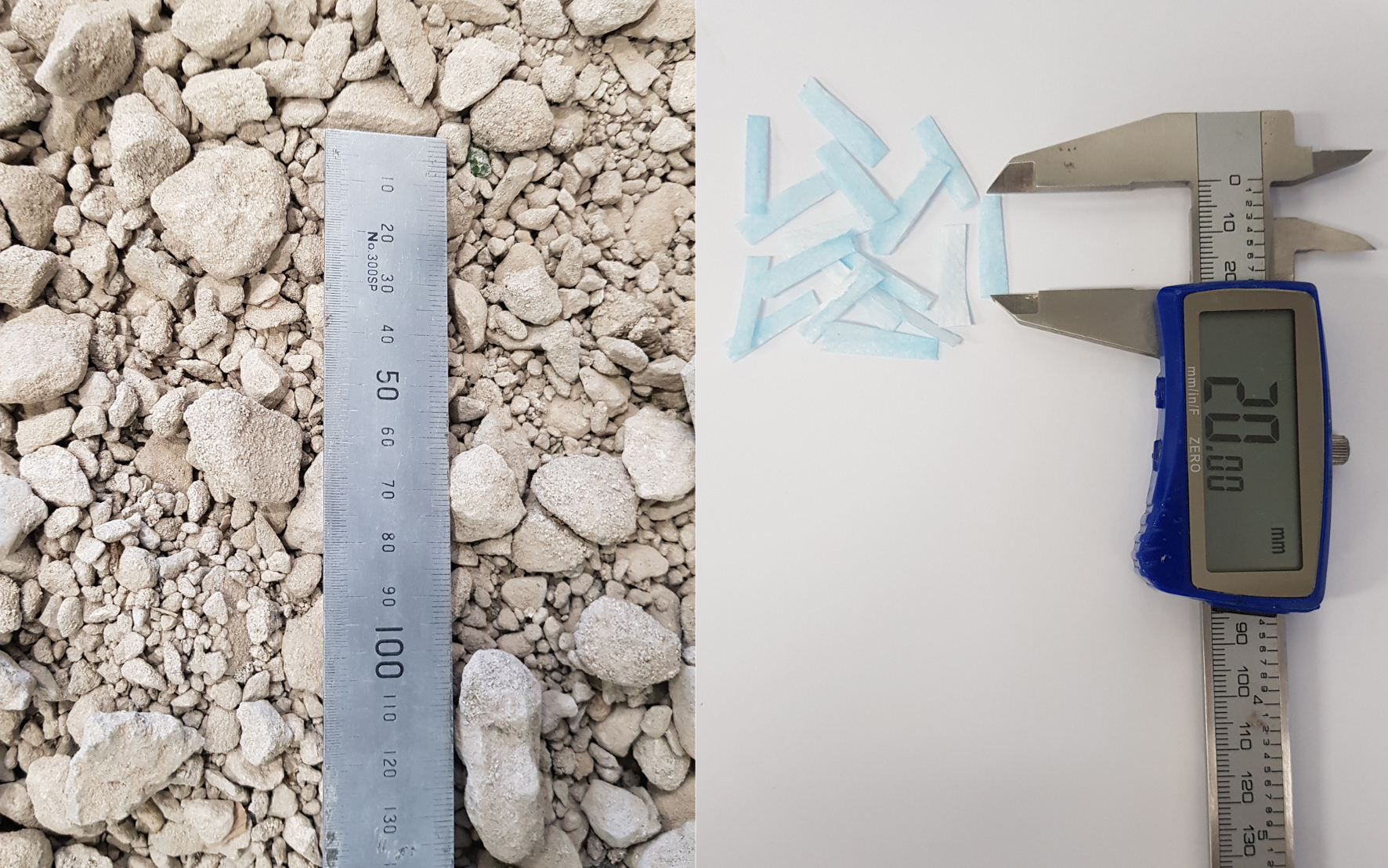

To accommodate RMIT’s safety and health policies during the pandemic, Li and his colleagues could work only with unused disposable surgical face masks. These were shredded into pieces measuring 0.5 cm wide by 2 cm long and then combined with recycled concrete aggregate in three mixes of 1%, 2%, and 3% face mask material. The 1% face mask mix provided the highest unconfined compressive strength and resilient modulus, which characterizes the subgrade’s ability to withstand repetitive stresses under traffic loadings, Li says. At mixes greater than 1%, the “excessive fiber inclusion would result in the loss of stiffness of the blended sample due to high amounts of voids,” Li reports.

The mask/concrete aggregate material was subjected to various tests involving specific gravity, melting point, water absorption, tensile strength, and other properties. At the 1% mask mix, the material met the necessary strength and stiffness requirements of traditional materials for pavement bases and subbases, Li says.

More studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of other types of masks than the plastics-based surgical style, Li notes. Because the goal of the RMIT research is to recycle the actual masks people have been wearing, Li and his colleagues also evaluated the effects of a thermal disinfection method — heating some masks in an oven to a temperature of 75 C. These tests indicated “minor effects on the strength and stiffness” would result from disinfecting used masks, Li says.

Looking ahead, Li and his colleagues hope to partner with local governments or industry to collect used masks and construct a road project prototype. They are also experimenting with how to use mixes of shredded face masks in the making of new concrete. Other forms of plastics-based personal protective equipment, and possibly nonplastic equipment as well, might also be recyclable into road materials to mitigate pandemic-generated waste, Li notes. Additional feasibility studies will be required.

The RMIT research, “Repurposing of COVID-19 single-use face masks for pavements base/subbase,” appeared in the Feb. 1 issue of the journal Science of the Total Environment.