By Robert L. Reid

Discovering that one major concrete bridge across a waterway was experiencing a serious issue with cracking would be bad enough for any city’s transportation department. But imagine the problem in Seattle where not one but two bridges — the second located adjacent to the first — faced issues with cracking concrete. Now add in the fact that the first bridge had to be shut down immediately once its cracking problem began getting worse while the second bridge had to accommodate detoured traffic.

Seattle faced this fascinating but unenviable challenge last year when the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge — the city’s busiest crossing, carrying more than 100,000 travelers a day over the Duwamish Waterway — was closed to all traffic on March 23, 2020. The cause was accelerated rates of cracking in the bridge’s concrete support structure. The cracks had first been discovered in 2013 during a routine inspection and then carefully monitored on an annual basis, rather than just every two years as federally required, according to information posted March 26, 2020, on the Seattle Department of Transportation’s SDOT Blog.

Concerns over cracking

The West Seattle High-Rise Bridge, completed in 1984 and known as the High Bridge, is a three-span, segmental, post-tensioned concrete box-girder bridge roughly 1,300 ft long that rises to a peak height of 140 ft above the Duwamish. Working with the international engineering firm WSP USA, SDOT had tracked the structure’s cracking over the years through digital devices and in-person examinations. But the cracks continued to grow despite critical maintenance efforts such as injecting epoxy into the cracks, the blog post noted.

Finally, early in spring 2020, significant new cracking was found. “This confirmed that cracking had rapidly accelerated to the point where there was no other option but to immediately close the bridge,” the blog post explained.

The seriousness of the situation was confirmed by the fact that even after the High Bridge was closed, the structure “continued to crack under just its own weight,” notes Matthew Donahue, P.E., C.Eng, M.ASCE, the director of SDOT’s roadway structures division and a certified bridge inspector under the U.S. Department of Transportation’s National Bridge Inspection Standards program. “Even after we had the vehicular live load off the bridge, we continued to see the same rate and amount of crack propagation on a daily basis that we had seen before.”

Detour restrictions

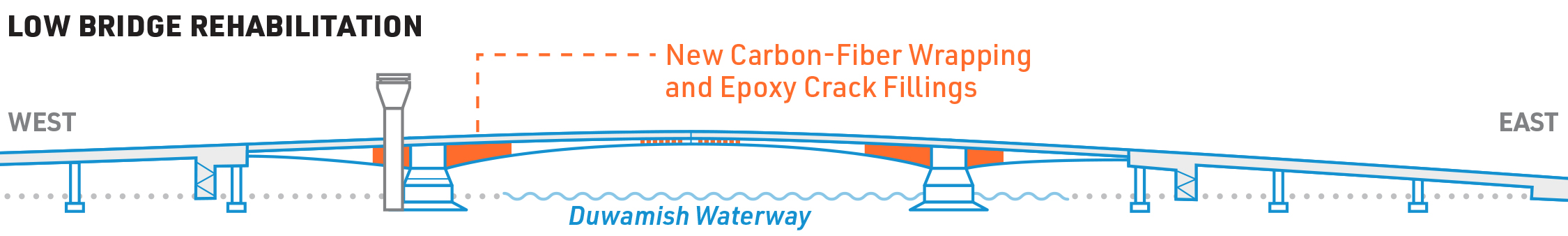

Fortunately, there was another bridge adjacent to the High Bridge, following the same east-west alignment across the Duwamish, that could carry some of the traffic that had previously used the now-closed main crossing. Unfortunately, that second bridge — officially called the Spokane Street Swing Bridge but colloquially known as the Low Bridge because of its 55 ft clearance — had also been experiencing concrete cracking, in this case since the late 1990s.

The Low Bridge’s cracks, however, were not expanding and were not considered to be as serious as what was happening to the High Bridge, according to a July 14, 2020, SDOT Blog post. Completed in 1991, the Low Bridge is also a post-tensioned concrete box-girder structure and features two 7,500-ton, movable halves that can swing apart to allow ship traffic to pass through.

The Low Bridge had previously been used mostly by commercial freight traffic and emergency vehicles. It was not designed to carry the full volume of traffic from the High Bridge, notes Donahue. Consequently, SDOT studied traffic data to determine the Low Bridge’s capacity throughout the day, he says.

Ultimately, SDOT imposed restrictions between 5 a.m. and 9 p.m., during which only designated vehicles could use the Low Bridge. These included emergency and freight vehicles, public transit and school buses, employer shuttles, and van pools. Pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers who had been granted waivers were also permitted. Any driver not in one of those categories who tried to cross the Low Bridge during the restricted hours faced a $75 fine, Donahue notes.

The restrictions were enforced first by uniformed police officers who questioned drivers as they approached the bridge. But by January 2021, SDOT was using an automated camera system to read license plates — a system that had to be approved by Seattle’s city council, given the city’s typical aversion to surveillance technology, Donahue adds.

Starting with stabilization

SDOT’s response to the dual cracking problems involved first a series of efforts to stabilize the High Bridge “to keep it from collapsing while we determined if we wanted to repair or replace” that structure, says Donahue. To determine the High Bridge’s structural integrity, SDOT conducted various nondestructive tests on the High Bridge — using ground-penetrating radar, ultrasonic tomography, and impact echo systems — and studied more than a dozen core samples and samples of the existing grout.

Both bridges were also heavily instrumented so that SDOT could keep a close watch on any changes — essentially tracking the cracking at one-minute intervals, around the clock, every day, Donahue says.

Prior to the installation of the full monitoring system, Donahue also went to the bridge site each morning with a skeleton crew of SDOT employees. He would then don the necessary safety equipment to enter the bridge via a small access panel and a 30 ft long ladder. Once inside, he would personally inspect certain key parts of the structure “to clear it for safe operation for the day” — for employees involved in the stabilization work from SDOT, WSP, and construction company Kraemer North America, based in Plain, Wisconsin.

Installed by Bridge Diagnostics Inc., of Louisville, Colorado, these monitoring devices included movement sensors to measure expansion and contraction at critical expansion joints, deck monitors to measure vertical and lateral bridge movements, vibrating wire crack gauges installed in critical girders to measure crack widths and movement, and cameras to record any visible increase in the cracks.

At key locations on the High Bridge — especially piers 15 and 18 — string pot displacement gauges are installed to monitor the structure as it expands and contracts, Donahue adds. One Alliance Geomatics also installed a shape array system to monitor the High Bridge for global movement. This device involves a linear survey system tied into GPS, with sensors on each side of the bridge, parallel to the long axis, Donahue explains.

The High Bridge stabilization plan was developed by SDOT and WSP and constructed by Kraemer. HNTB, headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri, served as the construction manager.

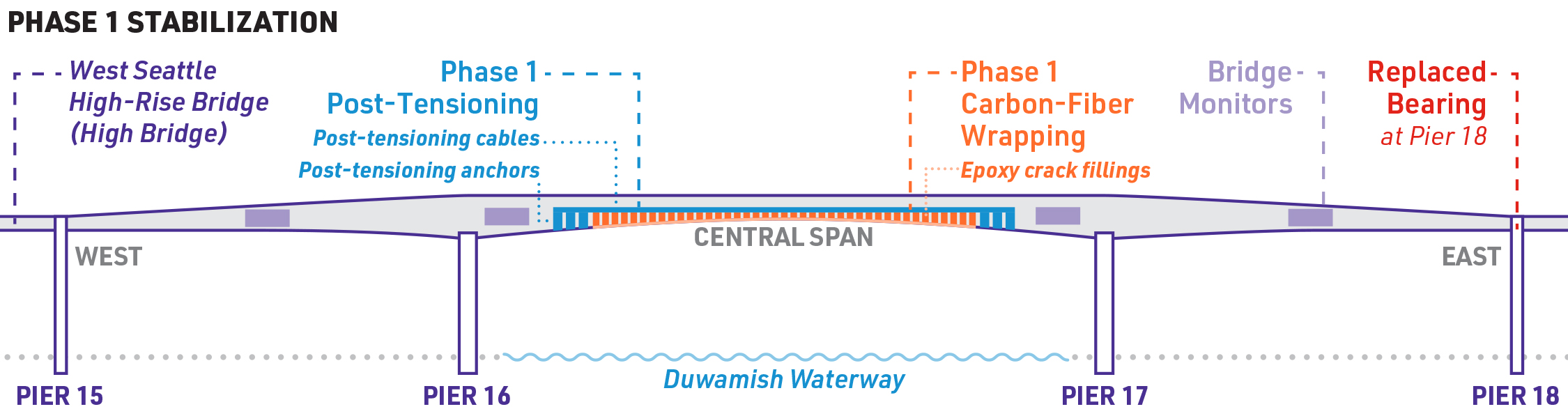

The stabilization efforts involved the installation of roughly 10 mi worth of new post-tensioning cables and post-tensioning anchors inside the hollow portions of the bridge’s box-girder structure. Epoxy injections were used to fill existing cracks to preserve the durability of the bridge, and key sections of the High Bridge were also wrapped with a carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer material to strengthen the structure in critical locations — similar to a cast placed on an injured limb, according to information on the SDOT website.

At pier 18, the lateral bearings “had gotten locked up” and deformed, Donahue says. This prevented two critical parts of the bridge that were normally independent of each other from moving as they had been designed to, “creating additional pressure on the surrounding area and affecting the bridge as a whole,” according to a Nov. 5, 2020, SDOT Blog post. So the damaged bearings were replaced, and new concrete was added to hold the new bearings in place.

All the High Bridge stabilization work was completed by December 2020.

Deciding to repair

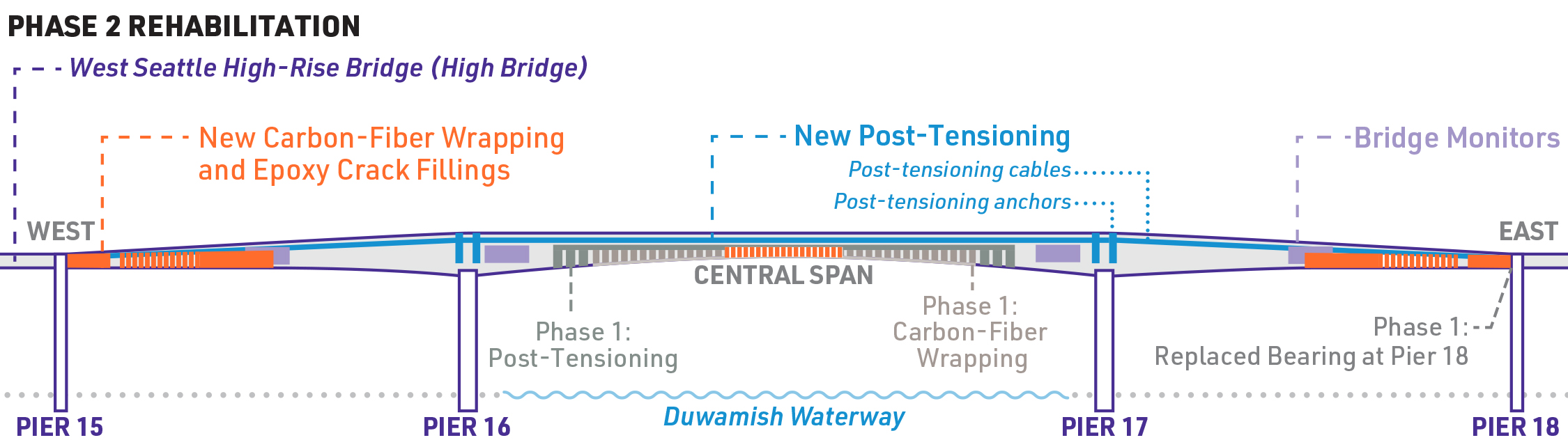

In November 2020, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan announced her decision to repair the existing High Bridge. This prompted SDOT to launch a second phase of work aimed at rehabilitating the crossing. The High Bridge rehabilitation work is still being designed, Donahue says, but the goal is to reopen the structure sometime in mid-2022.

On the High Bridge, the rehabilitation work will involve additional epoxy injections to fill cracks, the installation of more post-tensioning and carbon-fiber wrapping, as well as efforts to strengthen the bridge’s tail spans. Repairs to the Low Bridge will also involve epoxy injection and carbon-fiber wrapping, an upgrade to the control systems that enable the bridge to swing open and closed, and a refurbishment of some of the structure’s hydraulic systems.

Beyond the bridges

When a major bridge like the High Bridge has to be closed, “it’s no longer just a bridge problem,” Donahue says, “because now there are traffic implications, health and safety implications, race and social justice implications,” and other concerns.

Fortunately for SDOT, the department follows “a very robust, well thought out, meaningful outreach program” for all potentially disruptive projects, even smaller ones, Donahue says. These outreach efforts include working closely with a community task force, community leaders, and a technical advisory panel. In addition, Donahue praises the work of Heather Marx, SDOT’s director of downtown mobility, who is leading a program specifically charged with repair of the High and Low bridges, safety, traffic mitigation, and other problems that could result from the bridge closure.

To ensure the safety of people and businesses located near the High Bridge, SDOT established a roughly 225 ft wide “red zone” on either side of the bridge as an evacuation area should the structure seem ready to topple over in a worst-case scenario, Donahue says. SDOT worked with the Seattle police and fire departments, the port authorities, the U.S. Coast Guard, and others to be prepared to evacuate this area if such an event seemed imminent.

On several occasions, SDOT even conducted simulated emergencies in the middle of the night, in which all key stakeholders would be notified by phone of a pending disaster at the bridge site, Donahue says. “Then we’d all dial in and see the ‘fake’ data for the test, and we’d have to work that problem,” he says.

Maintenance success story

Although Donahue knows that some people in Seattle blame maintenance issues for the High Bridge’s problems, he argues that “this is actually a maintenance success story.” It was SDOT’s maintenance and inspection programs that “allowed us to catch the problem on the bridge before it became catastrophic,” Donahue explains.

At the same time, he points to ASCE’s 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, which warns that infrastructure maintenance overall is grossly underfunded. “We don’t have enough money to replace everything,” Donahue notes, “but if we get smart about what we need to do and start putting maintenance and rehabilitation money in the right place at the right time, we can extend” the useful life of these infrastructure assets. “If we don’t do it,” he says, “the price to be paid is that more and more bridges are going to be closed.”

It is too soon to tell what funding might become available for this project, or similar efforts, as a result of the recently passed Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

All drawings courtesy of SDOT