By Jay Landers

On Nov. 15, the long-awaited second phase of the Metrorail’s Silver Line began operating in northern Virginia, adding six stations and more than 11 mi of at-grade and aerial guideway to the already extensive transit system operated by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, commonly known as Metro.

The completed Silver Line enables rail service for the first time to and from Washington Dulles International Airport, which is in Fairfax and Loudoun counties and approximately 25 mi west of Washington, D.C.

Serving the nation’s capital and the larger region, Dulles Airport originally opened in 1962. Extending rail service to the facility has long been a goal of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, the entity that operates Dulles Airport as well as Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington County, Virginia.

“Building rail to Dulles was part of the original vision for the airport more than 60 years ago,” said Jack Potter, the president and CEO of the MWAA, in a Nov. 15 news release. “Bringing that vision to reality required talented teams of people working tirelessly toward a common goal.”

Long time coming

Completion of Phase 2 of the Silver Line wrapped up the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project, a nearly $5.8 billion effort that extended Metro’s rail service by 23 mi and added 11 stations. Metro’s rail system now comprises 128 mi of guideway serving 97 stations in Virginia, Maryland, and Washington.

Phase 1 of the Silver Line opened in July 2014, adding five stations and extending the system northwest 11.7 mi from the existing East Falls Church Station to the Wiehle-Reston East Station, an interim terminus on the eastern edge of Reston, Virginia, until the completion of Phase 2. Designed and built by Dulles Transit Partners, a team led by Bechtel Infrastructure, the approximately $3 billion Phase 1 project was overseen by the MWAA.

Phase 2 has been in the works for nearly a decade. In May 2013, the MWAA awarded a design-build contract for the stations, tracks, and systems associated with the project to Capital Rail Constructors, a joint venture of Clark Construction Group LLC andKiewit Infrastructure South. Preliminary construction began in 2014.

Substantially completed in November 2021, the project achieved its operational readiness date on June 23, 2022. At that point Metro assumed control of the Silver Line extension from the MWAA. Between then and its Nov. 15 opening, Metro tested the new tracks, equipment, and maintenance facility and conducted training and safety certification efforts.

Funding for the approximately $2.8 billion project came from the MWAA ($1.7 billion), Fairfax County ($527 million), the commonwealth of Virginia ($323 million), and Loudoun County ($276 million).

Many new features

As part of the Silver Line’s new features, Phase 2 also includes a 90-acre rail yard and maintenance facility on the airport property that was designed and built by Hensel Phelps Construction Co. The six new stations are Reston Town Center, Herndon, Innovation Center, Dulles Airport, Loudoun Gateway, and Ashburn and extend the Silver Line from Reston to eastern Loudoun County.

The platforms at the stations are 600 ft long to accommodate eight-car trains, says Stephen Barna, P.E., M.ASCE, the director of project engineering for the MWAA. “The station dimensions are established to coordinate with the length of the train,” Barna says. The structural bays of each station are 33 ft, 4 in. long, so that three bays equal 100 ft. Each platform is segmented into 18 structural bays.

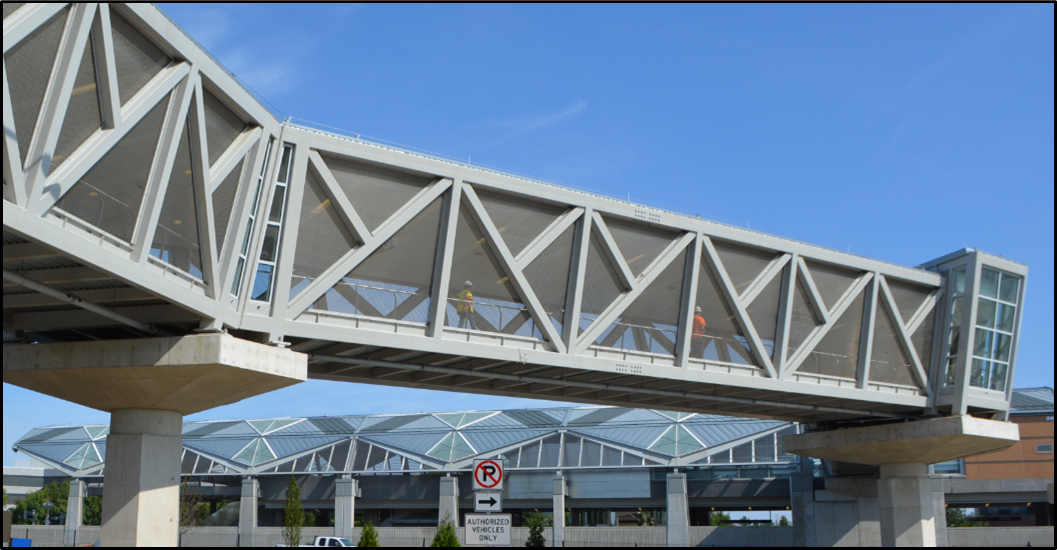

Five of the six stations were constructed at grade in the median of State Route 267, which includes the Dulles Toll Road and the Dulles Greenway, tolled roads that extend on either side of the airport, and the Dulles Access Road, a non-tolled route to the airport. Nine pedestrian bridges, all of which are 10 ft wide and vary in length from 300 ft to 400 ft, were required to facilitate the flow of pedestrian traffic between the at-grade stations and related facilities on the opposite sides of the roadways.

The pedestrian bridges comprise prefabricated steel components and were assembled at locations within 1-2 mi of their intended destinations. Although the assembled bridge components did not have to travel far, transporting the large steel structures to their respective job sites was a “logistical challenge that was unique for every location,” says Adam Rosmarin, a senior vice president for Clark and the construction project manager for the Silver Line project.

Elevated section

Although mostly constructed at grade, the Silver Line extension includes an approximately 3.3 mi long aerial section of the mainline guideway that connects to the Dulles Airport Station, the only elevated station among the new stations. The Dulles Airport Station’s mezzanine floor links to the airport’s main terminal by way of an indoor pedestrian tunnel with moving sidewalks. Another 1.5 mi of aerial guideway leads to and out of the rail yard and maintenance facility.

“The aerial guideway tracks sit over a cast-in-place concrete track slab supported atop pairs of prestressed precast-concrete track girders,” Barna says. The track girders are typically 5 ft, 3 in. deep and span up to 150 ft when crossing over the Dulles Greenway, he says.

“T-shaped piers that support inbound and outbound tracks have a pier cap that is 27 ft, 8 in. long, 8 ft tall, and 8 ft, 6 in. thick sitting over a single 8 ft diameter reinforced-concrete column,” Barna says. “Track girders sit on top of the pier caps with the track slab above. Center to center of track is 14 ft, 0 in., where two tracks are supported over a common pier.” The piers extend 20-30 ft into the ground.

Anchor bolts were used to fasten the girders to the concrete piers. Although seemingly straightforward, even this detail required “a lot of coordination and constructability between the actual construction team and the designers to be able to make that work,” Rosmarin says.

“If you set the anchor bolts at the same time as when you're pouring the concrete substructure, you run the risk of the anchor bolts getting out of alignment,” Rosmarin says. To avoid this problem, the design “essentially left block-outs in the substructure so that we could core drill for the anchor bolts later,” he says. To ensure that the subsequent drilling into the pier would not damage any of its structural rebar, polyvinyl chloride sleeves were installed into the piers to leave the space necessary for the drilling procedure. “It's a good example of working constructability and preplanning into the design,” Rosmarin says.

Critical challenges

Other critical challenges on the project involved contending with a job site that was more than 11 mi long, much of which was between major roadways. “The majority of this job was built in the median between two roads with traffic going 70 mph in each direction,” Rosmarin says. Ensuring the safety of workers and the traveling public was “very critical and important to us,” he says. “We were able to maintain a very good safety record over the course of the job.”

Major revisions to the project’s approach to stormwater management also proved a challenge to the project team, says Drew Hascall, a vice president in the Office of Engineering at the MWAA. “Well after the project was awarded, Virginia adopted new stormwater management criteria for both quantity and quality” as part of efforts to protect the Chesapeake Bay, he says. “We would have been within our rights to adhere to the old criteria because the project had been awarded and was permitted and under design,” he notes. However, the MWAA decided to adopt the more stringent criteria, given the “magnitude and the enduring nature of a project this size,” Hascall says.

As a result, most of the stormwater-related aspects of the project were separated from the main contract and bid as a separate design package. Won by the design and construction firm Dewberry, the package included the design and construction of 30 stormwater management features, including bioretention facilities and constructed wetlands, along the length of the railway, Barna says.

This article first appeared in Civil Engineering Online.