By Robert L. Reid

In Detroit, the renovation of a towering train station and establishment of a new mobility innovation district are reimagining transportation in the 21st century.

Long heralded as the automobile capital of the world, the city of Detroit is poised to move in a new direction — one focused on the future of urban mobility. That future rejects “the idea that a city will solely be dominated by cars,” notes Craig Schwitter, P.E., a senior partner and chair of the global board at the international engineering and design firm Buro Happold. Instead, new approaches to mobility will feature more of a “mixed mode where cars are alongside other forms of transportation,” including pedestrians, scooters and bicycles, public transit, and autonomous vehicles, Schwitter explains.

These ideas are being enacted in Detroit, where Michigan Central Station — a renovated, historic train station that reopened in June 2024 — is intended to be the centerpiece of a 30-acre mobility innovation district “offering new levels of tech infrastructure, including urban transportation solutions that advance a more sustainable, equitable future,” according to a press release from Buro Happold.

The firm provided multiple services for the renovation of the station itself as well as the surrounding mobility innovation district campus. This work included mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems for the station building as well as mobility planning, multimodal street designs, traffic modeling, e-mobility planning, pedestrian modeling, equity planning, and planning for “smart city” technologies “that improve urban living.”

Detroit is a city in which mobility issues “help and hurt ... at the same time,” Schwitter says. Automobiles helped the city grow, he explains, reaching a population of more than 1.8 million in 1950. But because of cars, the city increased in size rather than density, “growing wide,” Schwitter notes. Then economic changes hit the city, especially the decline of the U.S. automobile industry, and Detroit’s population began to fall by the late 1950s — dropping year after year to end up at roughly 631,000 by 2022. Consequently, Detroit found itself with “too much infrastructure to care for.”

“When you walk around Detroit, it’s a fabulous city,” Schwitter says. “But it’s wide, big, and lonely at times. You can walk on some streets in Detroit and not see another person.”

Renovating and rightsizing

The solution is for Detroit to “rightsize itself” through densification and sustainability — two concepts that are “linked from the perspective of urban planning,” Schwitter says. “Denser cities are generally more efficient and thus more sustainable.”

Key to that approach is the reuse of its existing building stock rather than “knocking down and starting afresh,” says Schwitter, who describes Detroit as “a poster child for building stock that was deteriorating” but is now in the process of being reused.

Perhaps the most prominent example of such reuse is the Michigan Central Station building, a 640,000 sq ft Beaux-Arts facility that features a 13-story office tower atop the station structure. It was a unique combination for its time, notes Schwitter, who explains: “You don’t see many train stations that started off as mixed-use developments.”

Opened in 1913 for the Michigan Central Railroad, the station is between the historic neighborhoods of Corktown and Southwest Detroit. It was an area that seemed likely to become a new urban hub, a huge development anchored by the station, Schwitter says.

Initially, the area grew. But after World War II, city planners began to demolish homes and businesses in preparation for industrial development that “never came to fruition,” followed in the 1960s by urban renewal projects and highway construction that further “swallowed up or flattened dozens of residential blocks,” notes the Detroit Historical Society.

Things began to change in the 1970s, however. The station was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, as was the remaining residential section of Corktown, which was also designated as a Historic District of the City of Detroit in 1978, the society explains. Then, starting in the early 2000s, Corktown enjoyed revitalization, with new restaurants and other businesses moving into existing spaces, efforts to promote affordable housing, and other improvements.

Rise, fall, and return

The city’s rise and fall and gradual return mirrors the history of Michigan Central Station, which closed in 1988 and at one point was threatened with demolition. In 2018, however, the station was purchased by Ford Motor Co. and subsequently restored by a multidisciplinary team that, in addition to Buro Happold, included the architecture firm Quinn Evans; Silman, now part of TYLin International, as structural engineers; the architecture firm PAU, which led the design of the mobility innovation district site plan; Giffels Webster as civil engineers; and Mikyoung Kim Design for the landscape architecture.

The revamped station and its surroundings will provide “a first-of-its-kind ecosystem combining Detroit’s rich history and its commitment to shaping the future of transportation worldwide to form a global hub for mobility innovation,” according to the Michigan Central website. The project’s goals extend beyond “the revitalization of a historic building,” the website continues. “[W]e are reimagining the very concept of mobility for the 21st century ... with initiatives and innovations developed here being used as models for urban centers around the globe.”

Among other services, Buro Happold performed a people flow analysis of the station building using advanced crowd modeling software to assess the impact of different event scenarios on the facility, such as large events in the main lobby, says Francesco Cerroni, a Buro Happold principal and the firm’s mobility leader. The people flow analysis helped test the performance of the circulation spaces, the elevators and elevator lobbies, and the capacity of the main entrances to the building — which was critical, because the project could not create any new openings in the structure since it is listed as historical, Cerroni notes.

The areas around the station provided key spaces for innovative mobility projects. For instance, on the back (southern) side of the station, an elevated, steel-framed platform had once provided access to the trains. Although it was originally considered as a potential site for testing new mobility systems, it quickly became apparent that the platform was not structurally sound and had to be dismantled, says Cerroni. In its place, a new concrete structure was erected to provide space for a public park that can accommodate various types of events, while beneath the new structure will be a parking garage in which different forms of autonomous parking technologies can be tested, Cerroni says.

Moreover, the park was designed so that at least a portion of the space could be used for the platform’s original purpose, in case freight or passenger rail service is ever restored. “Officials have hinted that rail service could return to the station, but nothing definitive has been announced,” explained a May 31, 2024, article in the Detroit News, “Everything to know about Michigan Central Station’s reopening.”

Relying on roads

Because the former train platform was no longer available to test mobility projects, the existing roads across the Michigan Central district took over that role, Cerroni says. For example, the roads around the station have become home to a series of inductive charging pilot projects. One of these projects, designed by the engineering firm Jacobs, features a quarter-mile section of 14th Street, to the east of the station, in which electromagnetic coils were embedded under the road surface to wirelessly charge electric vehicles equipped with special receivers as they drive overhead.

A second project involves a triangular piece of land adjacent to the station on which a static inductive charging system can power electric vehicles while they are parked. Both projects are underway.

A third wireless charging project, involving a three-quarter-mile-long segment of Michigan Avenue in nearby Corktown, is expected to start sometime in 2026 or 2027.

The Corktown area is also part of a pilot project for an electric, autonomous shuttle service known as The Connect that has been operating since August 2024. The shuttles follow a roughly 11 mi route, testing increasing levels of automation up to fully autonomous driving — although “a safety operator will remain behind the wheel of The Connect shuttles at all times,” according to the city of Detroit website.

Developing district

Other aspects of the Michigan Central mobility innovation district include the renovated book depository building, southeast of the station, which opened in 1936 as a post office and mail-sorting facility. It later became the book depository for the Detroit Public Schools system, was heavily damaged by a fire, and was then abandoned for decades. Restored by the architecture firm Gensler and structural engineers IMEG, the facility has been renamed the Newlab at Michigan Central and will serve as “an open platform” in which “everyone from startups to Fortune 500 companies” can “come together to work on solving the world’s mobility challenges and discovering new technology,” according to the Michigan Central website.

The Newlab is already home to more than 100 member firms, including Electreon, the wireless charging system developer that is part of the Michigan Central district’s inductive charging pilot projects.

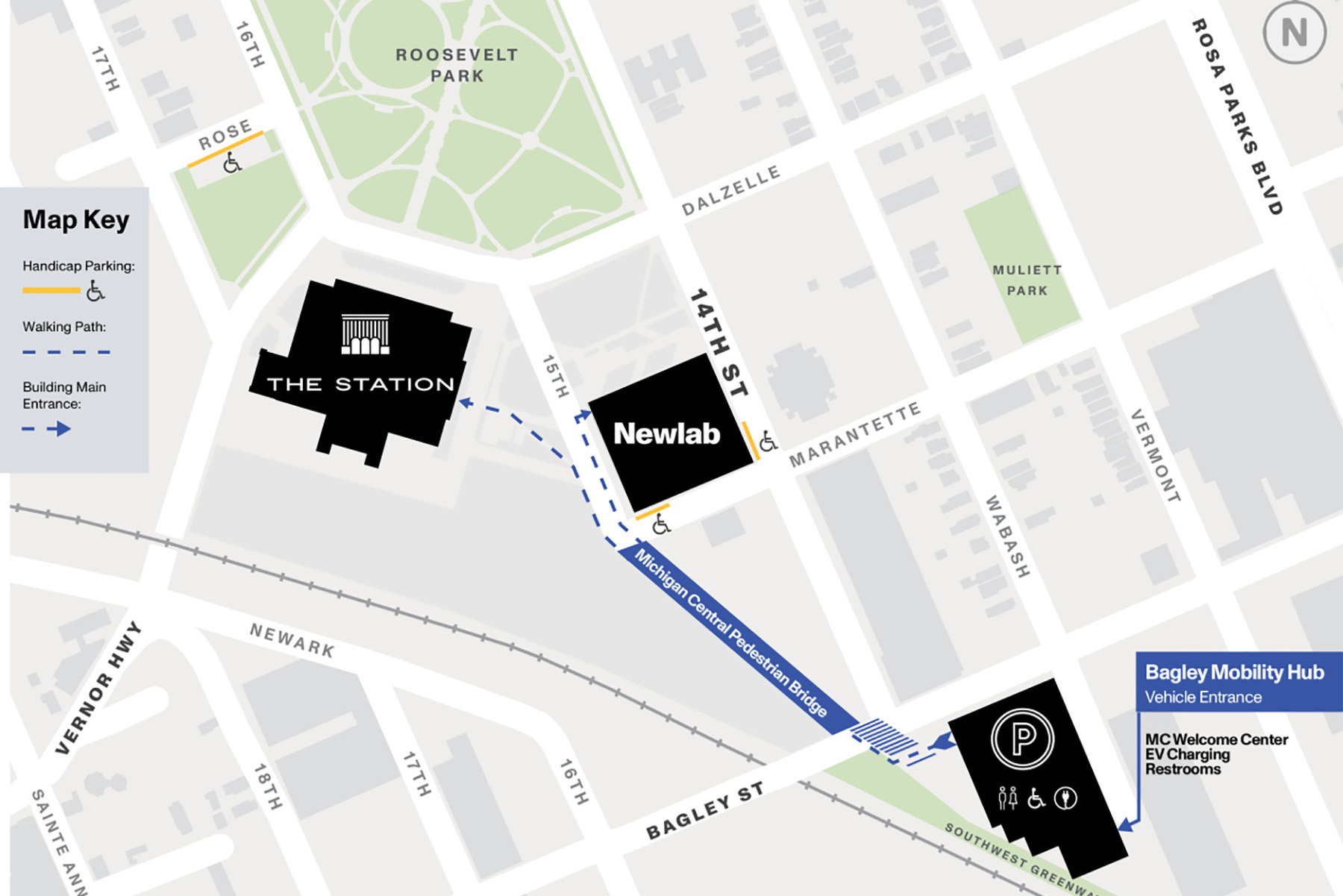

Continuing southeast of the station is the Bagley Mobility Hub, a newly constructed parking garage that will provide various services to the neighborhood. In addition to offering more than 1,200 parking spaces, the six-story site will also feature facilities for bicycles and scooters (including the electric versions of each), electric vehicle charging systems, and an autonomous vehicle testing area. As the first of a series of planned mobility hubs for people moving around within the Michigan Central district without automobiles, the Bagley site will also provide amenities such as shaded seating areas, a water fountain, restrooms, and information panels about the Michigan Central district, says Cerroni.

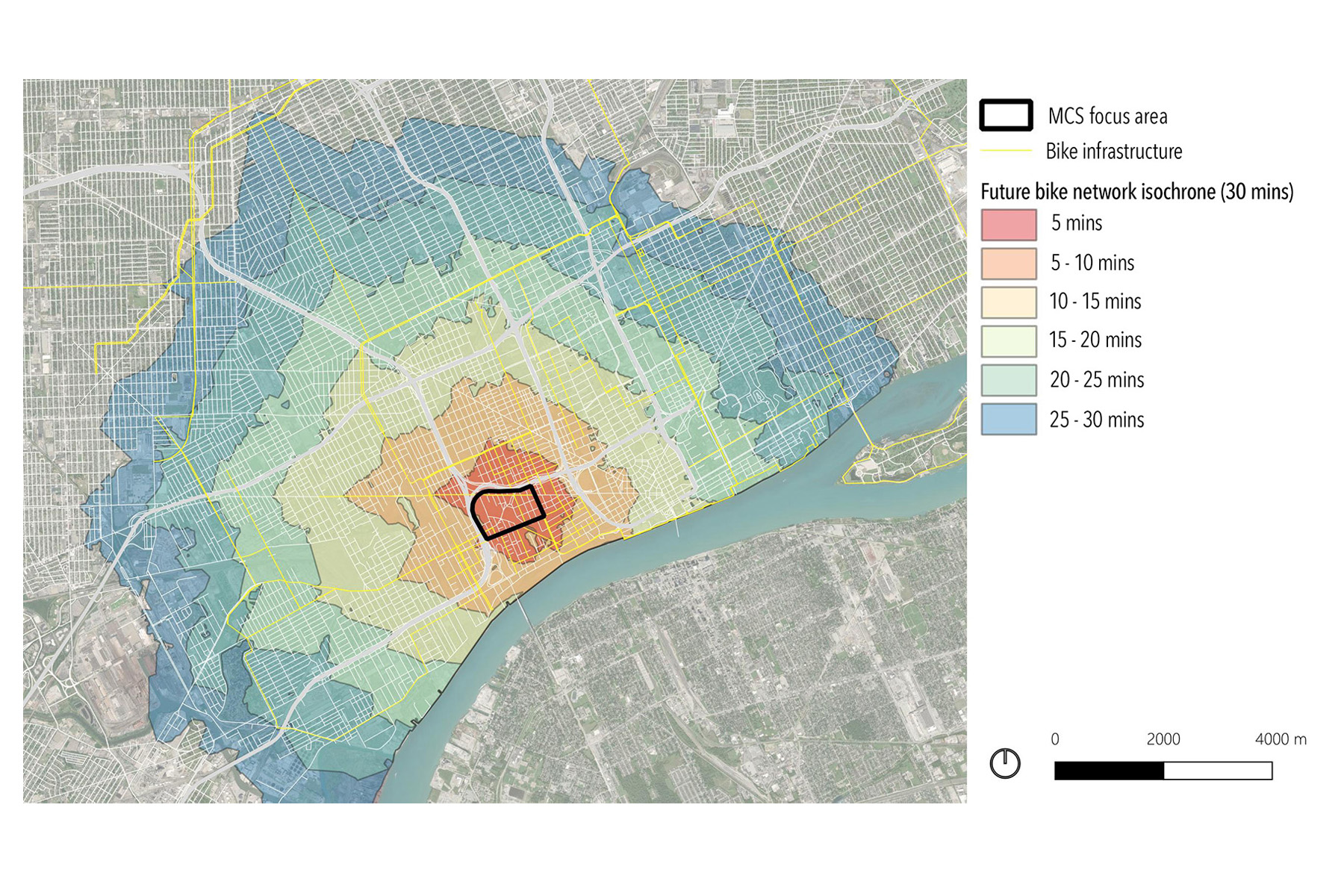

Buro Happold created an isochrone map to assess the accessibility of the station to nearby destinations, which helped determine the locations of the micromobility hubs with bike and scooter sharing docks, such as the Bagley garage. The Bagley garage also connects to the station building via 15th Street, which was converted to a shared-use path, Cerroni says. The route includes a pedestrian bridge that crosses over part of an old rail yard behind the station. It also provides access to the new Southwest Greenway, a roughly mile-long path that will link the mobility district to the Detroit waterfront and the Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Centennial Park, a 22-acre green space along the Detroit River that is scheduled to open this year.

The Factory, which was once home to hosiery and knitting businesses, now serves as the base for members of Ford’s autonomous vehicle business and operations team.

Additional buildings are planned west of the station, but their functions and exact locations are still to be determined.

A key section of the Michigan Central district has also been designated by the Michigan Department of Transportation as Detroit’s Advanced Aerial Innovation Region for developing and testing next-generation aerial mobility and drone technology. Considered the first cross-sector, advanced aerial urban initiative in the United States, the aerial innovation region will cover a 3 mi radius around the Michigan Central campus.

The project is scheduled to last two years and is intended to “propel solutions focused on addressing accessibility, safety, tech equity, and regulatory challenges by testing potential commercial drone uses — ranging from delivery of medical supplies, consumer goods, and manufacturing materials to infrastructure inspection,” according to the MDOT website.

Alternative approaches

When Buro Happold began work on the mobility district project roughly seven years ago, “there was no clear definition of what the district would look like and how it could attract and generate innovation,” Cerroni says. Moreover, the roads surrounding the development had been in disrepair and presented unsafe conditions for motorists and pedestrians. The neighborhood also lacked many basic services, such as access to public transportation.

Early in the district’s planning process, Buro Happold conducted a traffic impact study for Detroit’s Department of Public Works using Vissim multimodal traffic flow simulation software, manufactured by PTV Planung Transport Verkehr AG in Karlsruhe, Germany. Not surprisingly, the addition of a planned 1.2 million sq ft of new commercial development in the district, along with an estimated 5,000 workers as well as visitors, “implied increased traffic and possibly unacceptable levels of congestion,” Cerroni says.

At the same time, the study called for a reduction in the capacity of the area’s road network through measures such as the changes to 15th Street mentioned previously and the reconfiguration of parts of Lacombe Drive, which was a two-lane road in each direction but became a shared street without curbs that now provides space for pedestrians and cyclists.

Buro Happold’s analysis showed that alternative transportation measures would ultimately benefit the district by reducing the demand for vehicle trips and therefore the construction of new parking. “We showed that what was saved in building and operating additional parking could be used to promote the use of collective and sustainable modes, such as the implementation of the mobility hubs and (autonomous) shuttle system,” Cerroni says.

“What we did was to frame a vision in a set of strategies that ... we called ‘mobility use cases,’” he explains. “The objective was not only to create the condition for these mobility use cases to be developed in the district but also to create the actual physical conditions to make that happen, with the idea that the physical improvement to the district could also be enjoyed by the local population of Corktown and the entire city.”

Some of the use cases are being developed by teams within the Newlab incubator site, Cerroni adds, while others, such as the autonomous shuttles, are being tested around the area thanks to the creation by the city of Detroit of a Transportation Innovation Zone in the Corktown area. The zone features a “streamlined, adaptive permitting process designed to support cutting-edge technology while prioritizing safety and community engagement,” explains the city’s website. “This framework enables innovators to navigate regulations more efficiently, fostering an environment where innovation thrives, and Detroit leads in mobility advancements.”

Having worked on other innovation districts in the past, Schwitter and Cerroni express confidence in the future of the Michigan Central Station district and the city of Detroit overall.

The station is a beloved landmark whose reopening last year was feted with a concert featuring Detroit celebrities such as Diana Ross and Eminem — a unique way to introduce a renovated building and a new mobility innovation district, Schwitter notes.

The “emotion and raw feeling” that Detroit and the station elicit are incredibly important, Schwitter adds. “(They’re what make) a place a place — and that emotion is going to carry Detroit quite a way,” he predicts.

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Civil Engineering as “Planning Urban Mobility.”

Project credits for the Michigan Central Station renovation

Owner

Ford Motor Co.

Architect

Quinn Evans, Washington, D.C.

Structural engineers

Silman, part of TYLin International, San Francisco

Mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems; mobility planning; multimodal street designs; traffic modeling; and other services

Buro Happold, Detroit office

Mobility innovation district site plan

PAU, New York City

Civil engineering

Giffels Webster, Detroit

Landscape architecture

Mikyoung Kim Design, Boston