By Audrey Swain

Seattle’s downtown has a new “front porch” — a 20-acre urban park that redefines the city’s connection to its iconic waterfront, blending robust civil works, habitat-forward design, and people-focused places.

When the Washington State Department of Transportation removed Seattle’s Alaskan Way Viaduct — a double-decker freeway that ran through downtown — and replaced it with the State Route 99 tunnel, the city seized the opportunity to rethink and revitalize its waterfront, not just as a corridor for movement, but as a destination for people.

The subsequent transformation is the result of a multiyear, multiproject landmark effort.

“Ever since the 2001 Nisqually earthquake and the 2009 decision to build the SR 99 tunnel, it really opened up the opportunity for the city to reimagine our waterfront and reconnect our downtown core to the waterfront,” said Angela Brady, P.E., the waterfront office’s director.

“Today, Seattle’s waterfront represents the single most important transformational program in the city in 100 years.”

The Waterfront Seattle program “has opened public access and views that were previously blocked by the viaduct,” explained Paul Huston, a construction program manager at HNTB, which provided construction management services on the project.

“As one moves along the waterfront now, you can look east and see the city’s skyline. Turn around, and you are met with the beauty of Elliott Bay, the Olympic Mountains, and Mount Rainier. ... This is the ‘front porch’ Seattle has wanted for generations,” explained Huston.

Viaduct to vision

Planning for the waterfront transformation began in 2009, launching a yearslong process that included extensive environmental reviews, a worldwide design competition, and the input of more than 10,000 residents.

From the outset of the project, the city deliberately paired urban design and engineering to ensure a unified vision. It launched two separate procurements, one for urban design and the other for engineering and project management, and then brought the selected firms together as a single, integrated team.

The design was led by Field Operations, a New York City-based landscape architecture and urban design studio. Initially, a local engineering design team led by CH2M Hill (now Jacobs) was selected to partner with the city and Field Operations to create detailed design and engineering solutions that would carry out the vision.

In 2014, the city also created the Office of the Waterfront, Civic Projects and Sound Transit, which reported directly to the mayor. This helped ensure that decisions made on the project aligned with the public vision.

Recognizing the scale and complexity of the waterfront transformation, in 2018 city leaders adopted a programmatic construction management approach to guide the overall project delivery. This strategy ensured consistent leadership, technical expertise, and integration of the program, which took seven years to complete. The city engaged a joint venture between HNTB and Jacobs to provide comprehensive construction management services.

Two factors worked together to create a successful project. First was a flexible delivery model that allowed the project team to adapt quickly to changing needs, said Huston, “with many members cross-trained to fill multiple roles.”

The second factor was continuity: a co-located team that stayed the same from early concept planning through construction and completion, carrying institutional memory across packages and years. That continuity enabled the team to follow program-level strategies, such as sequencing disruptive work early; shifting the scope of work among packages; and coordinating with private developers, who were engaged in construction projects adjacent to the waterfront, to keep the city infrastructure functioning and accessible while the project was underway.

Major undertakings

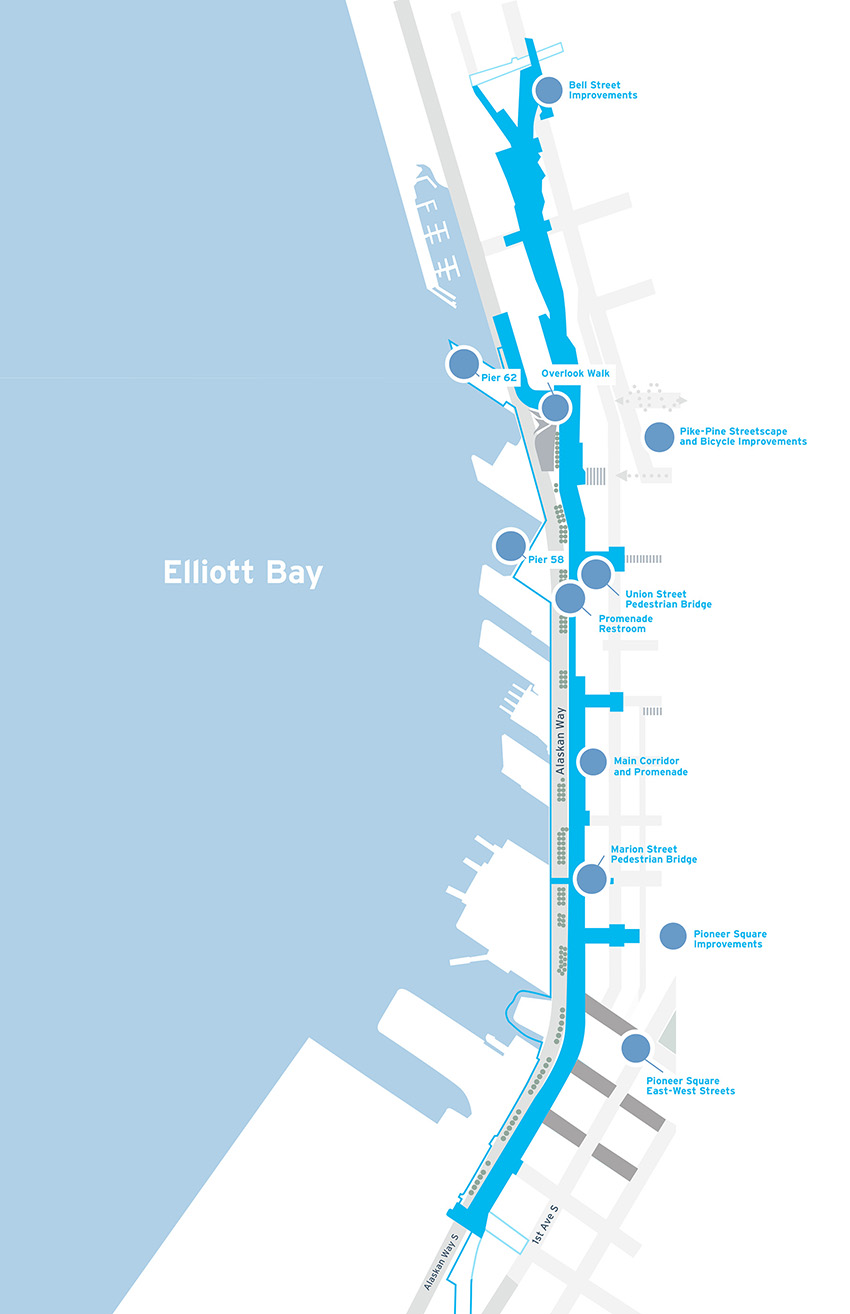

In total, the city’s Waterfront Seattle program featured nearly 20 major projects valued at $1.2 billion, representing one of the largest civic redevelopments in Seattle’s history. Prior to the construction of these projects, the city built a new seawall — which was not part of the work that HNTB/Jacobs delivered — to current seismic standards. It was designed to be the foundation for the waterfront projects, stabilizing the shoreline and ensuring the public’s safety.

There were nine waterfront projects in the construction management program led by HNTB/Jacobs. The most complex was the construction of the main corridor and promenade. With the removal of the viaduct, Waterfront Seattle rebuilt Alaskan Way between South King and Pike streets. The program also introduced a new street, Elliott Way, between Alaskan Way and Bell Street. Elliott Way is 17 blocks, running from South King Street in Pioneer Square to Bell Street in Belltown, with two lanes of traffic in either direction for the majority of the street. The new surface street creates a vital link to the trendy Belltown neighborhood, not only for cars but also for bikes and those on foot.

Alaskan Way and Elliott Way now form a multimodal main corridor that reconnects Seattle’s waterfront with surrounding neighborhoods. This main corridor enhances access to parks, businesses, and public spaces while supporting economic vitality and sustainability with more than 1,000 new trees and over 100,000 new plantings.

These improvements and additions also created space for a new park promenade and a two-way protected bike path along the west side of Alaskan Way. The park promenade is adjacent to the new waterfront — providing a new linear park between Pioneer Square and the Seattle Aquarium. This space facilitates access to the Seattle Ferry Terminal at Colman Dock, Seattle’s primary ferry terminal, and all the activities on the waterfront.

Another major improvement project is Overlook Walk, a multilevel elevated public park that seamlessly links several key areas to the waterfront, giving pedestrians a safe, scenic route above Alaskan Way. With views of Elliott Bay, Mount Rainier, and the Olympic Mountains, it features public plazas, terraced landscaping, and recreational spaces for people of all ages. The structure also connects at the roof level to the Seattle Aquarium’s new Ocean Pavilion, creating an integrated civic and cultural experience.

Overlook Walk also has an upper level that connects to the existing Pike Place Market. Additionally, there is a mid-level plaza that leads into the sidewalk adjacent to the roadway. Overlook Walk’s stairs connect to the promenade on the north end and the rebuilt Railroad Way pedestrian plaza on the south end. Each level of Overlook Walk offers its own view and character, creating many “best spots” for taking in the sights rather than one crowded vantage point.

Overlook Walk blends infrastructure with landscape architecture, adding approximately 60,000 sq ft of park space and bridging a 100 ft elevation difference. The structure is primarily reinforced-concrete decks and retaining walls with natural stone paving finishes and integrated wood seating.

Its foundations are reinforced-concrete columns, placed in isolation casings to minimize influence on adjacent structures. These foundations “sit near a 100-year-old railroad tunnel, adjacent to historic Pike Place Market, and (were) built while a new road and the aquarium’s Ocean Pavilion were under construction,” explained Andrew Barash, waterfront program manager.

Finally, the Pike-Pine Streetscape and bicycle improvement project enhances the multimodal connections between Seattle’s downtown and the Capitol Hill neighborhood, with wider sidewalks, new bike lanes, and improved lighting. Additional seating — such as benches integrated with the landscaping and platform-style seating areas near curbless street sections — encourages social activity.

Spanning 23 city blocks, these improvements required full roadway reconstruction, signal upgrades, and drainage and utility adjustments. Two bridges over Interstate 5, which runs along the West Coast and through Seattle, were retrofitted by adding sidewalks and bike lanes, plus a railing retrofit for an art installation.

Other improvements

Several smaller projects were carried out as well. The historic Pioneer Square connects to the waterfront through several blocks of upgraded streets and sidewalks, featuring vibrant landscaping, decorative bollards, and brick pavers that reflect the neighborhood’s historical character.

The new Union Street Pedestrian Bridge links downtown to the central waterfront. It features an accessible elevator, open stairway, and integrated public art inspired by native ferns. Replacing a narrow, aging metal staircase, this new reinforced-concrete bridge spans 93 ft, with an elevation change of about 55 ft from Western Avenue at one end to the promenade at the other end.

The Marion Street Pedestrian Bridge is a three-span bridge, including a 193 ft main span. It is a cast-in-place concrete superstructure that provides access to and from Colman Dock for more than 5 million users annually. The widened, modernized bridge replacement improves accessibility with ramp and elevator access and connects seamlessly to the new Alaskan Way corridor.

Another improvement is Pier 58, a new 48,000 sq ft structure that extends into Elliott Bay, featuring public event space, an aquatic-themed play area, landscaping, and water features. Its concrete deck panels are supported by steel piles with epoxy coating for corrosion resistance. Marine-grade stainless steel hardware was used for its durability in the saltwater environment.

Reaching westward by two blocks, Bell Street is an expanded park corridor that enhances the Belltown neighborhood with additional lighting, landscaping, and public spaces adjacent to Pike Place Market. These improvements required a roadway reconfiguration to make Bell Street a more pedestrian- and bike-friendly corridor along with an intersection redesign and utility adjustments. A salvaged bridge sign from the Alaskan Way viaduct is being restored and will be installed on Bell Street in the future.

Lastly, the Promenade Restroom is a new public facility that is adjacent to the centrally located Waterfront Park. It features six private all-gender stalls, reflective of the architectural and landscaping themes of Elliott Way.

- Additional projects that were not part of the HNTB/Jacobs work include a:

- Rebuilt historical pier for concerts and events.

- Restored historic pergola.

- 1.2 mi protected bike lane along the Seattle waterfront.

- Gateway linking the waterfront to Pioneer Square and the stadiums.

Overlapping efforts

The construction program unfolded in multiple stages beginning in 2018 with several projects having overlapping schedules and sites. At its peak, seven projects were underway simultaneously amid the bustling activity of an operational ferry terminal, seasonal cruise ship arrivals that tripled tourist traffic, active utilities, ongoing private construction, waterfront businesses, and daily residential life.

“The new main corridor was being built alongside new buildings and parking garages” being constructed by private developers, noted Brian Kittleson, HNTB construction engineer.

“We coordinated closely with those private developers and held regular meetings with the city’s permitting agency to manage traffic routing, work impacts, and detours — not just for our site, but across the entire area.”

Spurring investment

The completed works are already stimulating private investment and providing increased space for entertainment and artisan vendors in the region. In Pioneer Square alone, more than eight new businesses have opened since the improvements were completed at the end of 2024.

The owners cited the waterfront connection as a key reason for launching their operations there.

Philanthropic leaders have also stepped forward on a new endeavor: the Elliott Bay Connections Project, a $50 million gift-funded effort that will extend improvements north, enhancing several public parks.

Next on the city’s to-do list is to replace another mile of 1920s-era seawall north of Pier 62 and explore a new park at Pier 48 on the south end.

Civic reinvention

This transformation of Seattle’s waterfront is more than a feat in engineering and urban design; it is a civic reinvention. From better mobility and accessibility to vibrant public spaces and iconic views, the program delivers on a decades-old promise to reconnect the city with its shoreline.

With every trail, terrace, and transit connection, the new waterfront creates a lasting legacy of civic ambition — one that will serve generations of Seattleites and visitors to come.

“It’s mind-blowing to see how close our construction results are to the original concept renderings,” Brady said. “Seattle rebuilt our waterfront and stitched our downtown back into it so people could enjoy Elliott Bay, the Olympic Mountains, and all the waterfront has to offer.”

Audrey Swain is a senior communications manager for HNTB.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2026 issue of Civil Engineering as “Shoreline Success.”