Franklin Sherkow, P.E., ENV SP, is an ASCE Fellow and Life Member, and former President of ASCE’s Oregon Section. He was on the civil engineering faculty at Oregon State University for six years before returning to consulting. In today’s Member Voices, he examines how the lessons learned from the attack on Pearl Harbor seven decades ago can help us today.

Can we learn lessons from the attack on Pearl Harbor that we can apply to today’s organizations and situations?

Are they really relevant in a new century?

Can a military disaster from more than 75 years ago have a connection to today’s organizational performance?

Although it may be difficult to see how events from that December morning could continue to teach us about today’s experience, I believe those lessons learned can be translated to the organizations, associations, and groups of today.

Background

First, a brief note of historical context.

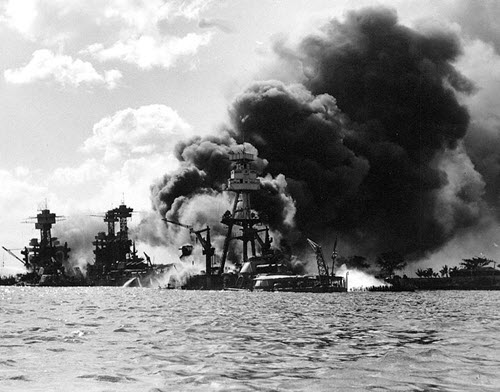

The attack happened on a Sunday morning. When the attack ended shortly before 10 a.m., less than two hours after it began, the American forces had paid a fearful price. Twenty-one ships of the U.S. Pacific Fleet were sunk or damaged. Aircraft losses were 188 destroyed and 159 damaged, the majority hit before they had a chance to take off.

The total number of military personnel killed was 2,335, including 2,008 navy personnel, 109 marines, and 218 army. Added to this were 68 civilians, making the total 2,403 people dead.

Pearl Harbor is recognized as the worst disaster in the history of the United States military. It thrust America into World War II in December 1941. The sneak attack by Japan was so jarring to the people, government, and armed forces of this country that it caused a series of nine formal investigations, including commissions, review boards, a court martial, a court of inquiry, and various Congressional committees. These investigations started within a few weeks of the attack (December 1941) and ran almost continuously to July 1946 (11 months after the war ended).

They were not only focused on the events leading up to the attack and the attack itself; they also explored how this type of disaster could be avoided in the future. Recall that this was the beginning of what was to become the Cold War with the Soviet Union. It was feared that the next sneak attack, if it came, would involve nuclear weapons, and the price paid would be considerably higher.

Lessons learned

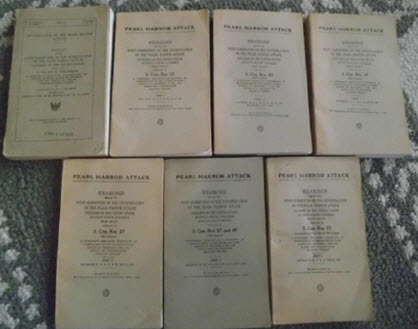

The last of the nine formal investigations into what happened at Pearl Harbor and what America should learn from those events was undertaken by a Joint Congressional Committee (Nov. 15, 1945, to July 15, 1946). Its final report was published July 20, 1946. The main report had 580 pages with foldouts and six volumes of hearing minutes containing 2,930 additional pages.

Edward F. Morgan, assistant counsel to the committee, focused on the U.S. Army and Navy supervisory, administrative, and organizational issues surrounding the Pearl Harbor attack and the events leading up to the attack. Morgan drafted 25 points for the report on deficiencies in these areas.

The applicability of these points far transcends Pearl Harbor, so they deserve serious review, even today and even for situations that go beyond military events and organizations.

Morgan’s supervisory, administrative, and organizational deficiencies in the U.S. military and naval establishments revealed by the Pearl Harbor attack (with modifications for today’s organizations)

1. Operational, financial, managerial, and executive work requires centralization of authority and clear-cut allocation of responsibility.

Morgan emphasized that the lack of “proper demarcation of responsibility” between the Navy and Army was not resolved before Dec. 7, and beyond question, prejudiced the effectiveness [of the Navy and Army defenses].” He went on to say that “The pyramiding of superstructures of organizations cannot be inductive to efficiency and endangers the very function of [any organization].”

2. Supervisory officials cannot safely take anything for granted in the alerting of subordinates.

Many witnesses in the Pearl Harbor investigations said, “I thought he was alerted,” or “I took for granted that he would understand,” or “I thought that he would be doing that.” Don’t assume that all appropriate parties to a given situation already know what is happening, especially in the early stages of an unexpected event. Make sure that they know.

3. Any doubt as to whether branches and departments of an organization should be given information should always be resolved in favor of supplying the information.

As the United States was decoding secret Japanese messages about a possible war deadline, Washington officials in the Navy and Army on Dec. 7 thought defenses at Hawaii were ready and on a “war footing.” They were not.

4. The delegation of authority or the issuance of orders, policies, or instructions entails the duty of inspection to determine that the official mandate is properly exercised.

The Navy officials in Washington failed to ensure that those in Hawaii took a defensive deployment upon receipt of the “war warning.” The job of an administrator, executive, or manager is only half-completed by the issuance of an order, policy, or instruction; it is discharged when they determine the order/instruction has been executed.

5. The implementation of official orders, policies, or instructions must be followed with closest supervision.

U.S. Army and Navy “top brass” did not follow through to ensure their orders were being followed.

6. The maintenance of alertness to responsibility must be insured through repetition.

Morgan disagreed with the school of thought which held that repeated warnings could blunt alertness by making the warnings commonplace. In other words, better to send a fire truck to nine wild-goose chases than to hesitate the 10th time and allow a major conflagration to burn out of control.

7. Complacency and procrastination are especially out of place where sudden and decisive actions are of the essence.

Morgan observed that Army and Navy officials in both Washington and Hawaii “were beset by a lassitude born of 20 years of peace.”

8. The coordination and proper evaluation of budgets, personnel, demand for services, costs, alternatives, and competition, in times of stress, must be insured by continuity of service and centralization of responsibility in competent managers and executives.

Morgan concluded that the system of handling critical information was seriously at fault and that centralization of this task was very much needed.

9. The unapproachable or superior attitude of officials, managers, and executives is fatal: There should never be any hesitancy in asking for clarification of instructions or in seeking advice on matters that are in doubt.

Morgan observed that in all of the records of “various interpretations as to what War and Navy Department dispatches meant, in not one instance does it appear that a subordinate requested clarification.”

10. There is no substitute for imagination and resourcefulness on the part of supervisory personnel, managers, and executives.

Morgan believed that with a better appreciation and application of [critical information], plus a little imagination, “someone should have concluded that Pearl Harbor was a likely point of Japanese attack.”

11. Communications must be characterized by clarity, forthrightness, timeliness, and appropriateness.

Morgan pointed out that the evidence reflected “an unusual number of instances where military officers in high positions of responsibility interpreted orders, intelligence, and other information, and arrived at the opposite conclusion.”

12. There is great danger in careless paraphrase of information received and every effort should be made to [ensure] that the paraphrased material reflects the true meaning of the original.

Morgan observed that there were instances where orders issued could have been interpreted in several different ways. This is especially true with today’s electronic communication and social media.

13. Procedures must be sufficiently flexible to meet the exigencies of unusual situations.

According to Morgan, the evidence showed that in both the Army and the Navy, everything “seems perforce to have followed a grooved pattern regardless of the demands for distinctive action.” People in the organization should, of course, have some understanding of how far that flexibility will go.

14. Restriction of highly confidential information to a minimum number of officials, while often necessary, should not be carried to the point of prejudicing the work of the organization.

Morgan concluded that those in charge of top-secret intelligence about what the Japanese were doing made no provision to analyze and chart the data, which would have given them day-to-day linkage from which to forge a chain of reasoning and deduction. Cumulative collection and analysis of critical information is basic, but to be useful, it must be interpreted and disseminated.

15. There is great danger of being blinded by the self-evident.

Morgan observed that U.S. Army and Navy had conducted war games against a Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor, but when the reality came on Dec. 7, all concerned were surprised.

16. Officials, executives, and managers should, at all times, give subordinates the benefit of significant information and ask for their input or ideas.

Morgan concluded that if subordinates had better information derived from critical intelligence, they might have been able to recommend better defensive positions and preparedness.

17. Managers and executives who neglect to familiarize themselves in detail with their organization should forfeit their responsibility.

Morgan touched on the problem inescapable in large organizations – how to achieve adequate familiarity with details without becoming overly absorbed in those same details (micromanaging); how to delegate authority while holding reins; and how to distinguish professional coordination from personal cooperation.

18. Failure can be avoided, in the long run, only by preparation for any eventuality.

U.S. military leaders in 1941 were far too concerned with what Japan might do, and not what it was able to do. Yet history has shown that if an enemy can launch a certain kind of attack, in all probability they will do exactly that. Their intentions cannot hurt their opponent; but their capability can, if properly utilized.

Risk analysis can be applied to any project or organization but is often ignored.

19. Officials, executives, and managers, on a personal basis, should never countermand an official instruction.

Morgan regarded as extremely dangerous that the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations expressed an opinion on a personal basis to outpost commanders which inevitably downplayed the impact of the official dispatch. This will have the inevitable effect of tempering the import [of] other official communication, policy, or instruction.

20. Personal, professional, or official jealousy will wreck any organization.

Morgan noted that various squabbles between the Army and Navy led to a wide range of preattack problems, lack of coordination, and misunderstandings.

Hearings on Pearl Harbor Attack (1946).

21. Personal friendship … should never be accepted in lieu of professional or organizational liaison, or confused therewith where the latter is necessary to the proper functioning of two or more agencies.

The U.S. Army and Navy commanders in Hawaii simplistically confused their cordial personal interchanges with true close-knit coordination of professional activities which should have existed, but did not.

Keep the relationships on an organizational basis. They can still be cordial. It must go beyond personal friendship at any given organizational level. As personnel change over time, these relationships must endure.

22. No considerations should be permitted as excuse for failure to perform a fundamental task.

Morgan noted that the Army and Navy commanders in Hawaii asserted that they “had countless and manifold duties in their respective positions.” He then noted, “No excuse or explanation can justify or temper the failure to discharge their [primary defensive] responsibility which superseded and surpassed all others.”

This goes all the way to the top of any organization!

23. Managers and executives must, at all times, keep their subordinates adequately informed and, conversely, subordinates should keep their superiors informed.

Morgan states that there was a failure to inform the essential and necessary officers in the [Army] commands of the acute situation upon receipt of the “war warning” just prior to Dec. 7. Timeliness of such information and understandability should also be essential to this item.

24. The administrative organization of any establishment must be designed to locate failures and to assess responsibility.

Morgan pointed out that there was no system in place to determine who had seen or acted on critical information [intelligence] leading up to the Japanese attack. “What you don’t monitor, you won’t manage.” Managerial systems must be in place and working to monitor, audit, and identify critical functions in a timely manner. When failures are identified, timely corrective actions must follow.

25. In a well-balanced organization, there is close correlation of responsibility and authority.

Morgan noted that no one in Washington or Hawaii, “except the highest ranking officers, possessed any real authority to act in order to decisively discharge their responsibilities.” To vest someone with responsibility and no corresponding authority is an unfair, inefficient, and unsatisfactory arrangement.

Conclusions

These 25 points can and should serve as an audit list for organizations of any size, whether private, public, or nonprofit. For each, the order of importance and relevance may change, but the underlying list is fairly complete and should be used and reviewed on an ongoing basis.

What happened on Dec. 7, 1941, hopefully will never be repeated. But it stands as a beacon of what we can learn in terms of organizational deficiencies and how to avoid them. These lessons have relevance to today’s organizations. Whether events are or could be catastrophic or just mildly disappointing, correcting organizational deficiencies now will have the effect of making these events less impactful or our avoiding them altogether.

Readers can contact Frank with comments by emailing [email protected].