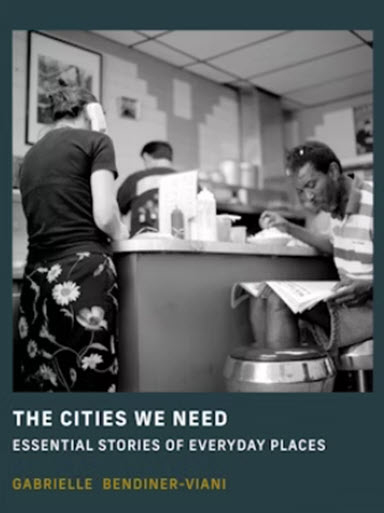

The Cities We Need: Essential Stories of Everyday Places, by Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2024; 288 pages, $39.95.

Why do we love a place? More specifically in the context of this book, why do we love a city or a neighborhood? In significant part, it’s usually because we love the people and the places. And it’s not too hard to realize that the people shape the places and just as surely those places shape us in return.

Author Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani holds a doctorate in environmental psychology and is an accomplished photographer, a “visual urbanist,” and co-founder of Buscada, an interdisciplinary studio focused on creating better spaces. She has been working on The Cities We Need for two decades – for longer, in fact, than she knew she would write it.

Further reading:

- Want to put AI to work to benefit your career or business? Here’s how

- Engineers have come a long way, but we still can’t control nature

- Book offers architectural walking tour vignettes of New York City

Researching “everyday places” in the U.S., London, and Buenos Aires, Argentina, she noticed a common thread of seemingly unassuming places having outsized meaning to those who lived there. Curious to understand more deeply, she quickly realized that quizzing people with direct questions wouldn’t get her there.

“It’s hard to talk about what it’s like to live our everyday lives because mostly, we just get on with it,” she writes. “The cyclical and improvisational rhythms of everyday places are hard for people to talk about or even notice.”

She hit on a solution, though: She began asking people to give “guided tours” of their neighborhoods. What they showed her, what they talked about, and how it affected them was up to them. These tours were necessarily very personal and gave her snapshots of, in her words, “how a city is lived – through the experience of a few of those lives.”

The Cities We Need was built from stories that seven such tour guides told the author about the Prospect Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, along with another five in the Mosswood neighborhood of Oakland, California. The two locations are therefore touchstones that help ground the book in real examples, while also functioning as stand-ins for any number of other neighborhoods in other cities.

In both places, many – if not most – readers who have lived in cities of any size will recognize echoes of their own places – not in the hyper-specific details but in the outlines, in the lived-in feel that is being described.

That feel, generated by the everyday places that do so much to define communities big and small, is doing actual work in helping bind people together, “laying the groundwork for a functional society,” the book says. It’s appropriate, then, that Bendiner-Viani refers to the idea as “placework.”

What kind of places does she mean? Diners. Barbershops. Parks. Libraries. Churches. Not necessarily every diner, though, nor even every park or church.

The special places – some of which, of course, will be in the eye of the beholder – are most often made so by the people who created them or the people who frequent them. What makes them so special – so essential – may not even be their primary purpose. A special diner may not have the best food, but it might have the best vibe or the best mix of locals and visitors or the most beloved or loquacious or cantankerous owner or cook.

A special park may not be the newest, biggest, or most well-kept, but maybe it’s in a central location, or it’s just where everyone has gone for so long no one remembers why or how it became the spot.

The deep immersion of the book’s approach allows Bendiner-Viani to explore a wide range of topics. Not least of these is how forces great and small, avoidable and (at times) unavoidable can result in the loss of these important places – reinforcing the need for leaders and indeed all of us to make considered decisions, to cherish and support the places we love, and to push back when it’s worth doing so against the relentless pressure to replace the old with the new.

Sometimes the value of the old and the familiar adds more to our cities, communities, and lives than the shiny and new adds in revenue or property values.

The book makes excellent use of dozens of the author’s photographs to give readers another window into Brooklyn and Oakland and the kinds of places (and people) the book is zeroing in on.

Meditative and deeply researched, piercingly provocative as the author probes the underlying issues that often threaten cherished places, but also affectingly personal via the words of the tour guides, The Cities We Need might just be the book you need right now for many examples and doses of everyday joy and community.