The rotating blades of wind turbines have become a common sight along highways and hillsides, especially in rural areas. Most of these tend to be the traditional horizontal axis wind turbines, which feature a towering mast, 100 feet or more in height, with key equipment in a nacelle atop the tower and enormous blades that generally must turn into the wind to spin and generate electrical power.

But if one Canadian engineer has his way, a new form of vertical axis wind turbine might eventually join the renewable energy mix.

Further reading:

- The renewable energy source right beneath our feet

- Tapping anaerobic digestion’s potential as a renewable energy source

- Multiuse sites make renewable energy more efficient and economically viable

The utility of VAWTs, which often feature a so-called eggbeater blade design, has long suffered from the fact that VAWTs tend to be shorter than HAWTs, which means they cannot access the stronger winds that blow at higher elevations. VAWTs also generally operate at a slower rotational speed than HAWTs, which limits their power-generating capacity. And VAWTs often need to be secured at the top by guy wires that spread out their overall footprints.

Stacked solution

Such problems, however, can be overcome by stacking two or more VAWTs and enclosing these systems within a stayed-column boxed frame for stiffness, said Glen Lux, a mechanical engineer in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. His firm, Lux Wind Power, has constructed more than 50 traditional VAWTs over the years and recently has been designing the new stacked, framed systems and developing small-scale prototypes.

In one prototype, erected in Saskatoon, the structure stands 90 feet tall and features three levels of cubic frames. Each cube measures 30 feet across and 30 feet tall per side and is constructed from beams made of square steel tubing either 2 inches by 2 inches in cross section or 3 inches by 3 inches, depending on location.

Courtesy of Lux Wind Power

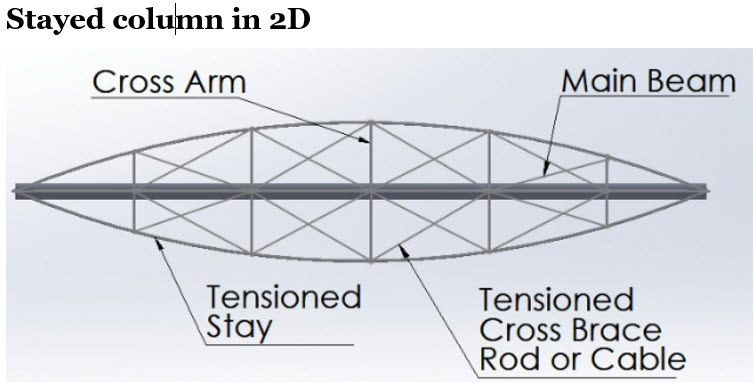

Courtesy of Lux Wind Power Tensioned diagonal cables that cross each side of the cubes keep the horizontal and vertical frames in compression even under extreme wind loads. To prevent buckling, the beams feature cross arms at one or more locations while stays – pretensioned cables or rods – are attached close to the ends of the beams and at the end of each cross.

The aluminum blades and the entire rotor systems are supported by the bearing at the bottom of the structure and at the points where the horizontal cables cross. The only major forces acting on the cubed frame are the thrust forces from the wind on each turbine and gravity from the frame above it. Because the ends of the horizontal and vertical beams can be considered as pinned, the design prevents bending moments, torsion, or shear on the beams.

The prototypes are founded on concrete blocks, one beneath each of the four legs, Lux said. Larger-scale versions would likely be supported on concrete pillars.

The framed, stacked VAWT was specifically designed for H-style rotors, but it can easily accommodate other types of vertical systems, including Darrieus turbines, Lux added.

Triple turbine

Although the protypes generally feature just two turbines (with an open cube at the bottom, where the wind is often slower but more turbulent), Lux said the optimal number of turbines will likely be three or four. For example, Lux said he has designed a triple-turbine structure with cubes large enough to reach 720 feet above the ground without the need for any guy wires.

Lux used a numerical analysis procedure known as the stiffness probe method, developed at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to compare the triple-stacked, 5-megawatt VAWT to a 5-megawatt reference HAWT used by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory for studies. The Lux VAWT can accept a thrust (wind) force of 650,000 pounds with a maximum deflection at the top of 50 inches. NREL’s estimated maximum thrust force was less than 200,000 pounds. Moreover, the frame of the triple-stacked VAWT would weigh less than the tower of the NREL reference turbine – 565,400 pounds versus more than 765,000 pounds – while standing over 200 feet taller than the 500-foot HAWT.

Vertical advantages

Lux said the stacked, framed design provides many advantages compared with horizontal systems. These include:

- The VAWT’s mechanical and electrical components are on the ground, rather than high in the air.

- The VAWT blades do not need to be turned into the wind. The system accepts wind from all directions.

- Multiple stacked turbines can achieve a rotational speed similar to or even higher than an HAWT of the same power rating. This lowers the cost of gearboxes or direct drive generators.

- It has been demonstrated that VAWTs can be spaced closer together than HAWTs, which often have a large wake turbulence that reduces the wind speed downstream. By contrast, the wake from several VAWTs, placed strategically, can enhance the wind speed and increase power production.

- A VAWT’s aluminum blades would be fully recyclable, compared with HAWT blades, which are generally made from nonrecyclable fiberglass or carbon fiber and an epoxy resin.

- Unlike HAWT blades, the VAWT blades do not need pitch control. The power and speed are regulated through electrical and mechanical systems and aerobrakes can also be installed if more control is required.

- The four-sided design and low center of gravity would also make it easy to use one or more stacked VAWT systems on floating platforms, something that is more challenging for the top-heavy HAWTs.

Moving forward

The Lux VAWT is designed to connect to the local electrical grid or provide power to individual locations, such as farms and other operations that consume large amounts of energy. At least one company has contacted Lux about putting the system on the roof of its building.

Lux has posted technical details and analyses about the design of the stacked, framed VAWT on his company’s website and invites engineers and other interested parties to review this information and contact him to discuss the technology. At the moment, his chief goal is to “get people interested and talking about it,” Lux explained, adding that he realizes the idea is new and “will take time and convincing to be accepted by industry.”

Get ready for ASCE2027

Maybe you have big ideas like the ones this engineer has put forth. Maybe you are looking for the right venue to share those big ideas. Maybe you want to get your big ideas in front of leading big thinkers from across the infrastructure space.

Maybe you should share your big ideas at ASCE2027: The Infrastructure and Engineering Experience – a first-of-its-kind event bringing together big thinkers from all across the infrastructure space, March 1-5, 2027, in Philadelphia.

The call for content is open now through March 4. Don’t wait. Get started today!