Long before lead in drinking water became a common concern, the Louisville Water Co. began a concerted campaign to identify and remove publicly owned lead service lines from its distribution system. Earlier this year, the utility completed this long-term project, marking a major milestone in its efforts to ensure the safest possible drinking water for its customers.

Amid growing concern regarding lead levels in drinking water in various areas throughout the United States, the Louisville Water Co., in Louisville, Kentucky, recently achieved a notable goal. After 50 years and a $50 million investment, the company removed its last known public lead service lines in March, a milestone reached by only a few other U.S. utilities.

Louisville Water started as Kentucky’s first public water provider in 1860. Situated along the banks of the Ohio River, the utility began with an ornate pumping station and water tower, a small reservoir, 512 customers, and 26 mi of water main. Today, it delivers an average of 119 mgd of drinking water to nearly 1 million people in the Louisville region by way of its 4,272 mi of water main.

Louisville Water has a rich history of engineering and innovation. The original facilities are National Historic Landmarks, and the Louisville Water Tower is a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. In 1896, George Warren Fuller conducted his groundbreaking experiments in filtration in Louisville, and today the two water treatment plants rank in the top 18 in North America for outstanding water quality, according to the Partnership for Safe Water. Louisville Water was also the first utility to combine collector wells and a tunnel as a source for drinking water. In 2011, this initiative, known as the Riverbank Filtration project, received ASCE’s Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement award.

When Louisville Water began, it was common to install a lead service line to connect to a customer’s property. Between 1860 and 1936, the company installed an estimated 74,000 public lead service lines before switching to copper service lines. (Lead was also used briefly during World War II in the 1940s when copper was required for the war effort.)

Lead has been a well-documented public health concern for decades. In the 1970s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency increased its focus on the health implications of lead in the environment, primarily from automobile exhaust. This examination triggered a closer look at the use of lead in various applications, including lead service lines. Recognizing early on the deleterious health effects of lead, Louisville Water took a leading role in addressing the problem, much as it had in the case of filtration. As a result, the utility began replacing its public lead service lines at this time.

Louisville Water has worked to ensure that its drinking water is safe and in full compliance with the EPA’s 1991 Lead and Copper Rule, which minimizes lead and copper in drinking water by reducing water corrosivity and exposure — usually from lead pipes, lead solder, and brass or bronze faucets and fixtures — to these elements.

Removing the lead service lines, educating the public, and optimizing water treatment make up Louisville Water’s three-prong strategy. Proper treatment is essential in producing water that will not corrode metal pipes or plumbing components that may contain lead. Educating members of the public on how to maintain high standards of water quality in their homes, facilities, and businesses is also essential.

Minimizing the risk of lead in drinking water begins at Louisville Water’s two treatment plants. A thorough daily evaluation is conducted on the source water, throughout the entire treatment process, and on the final finished product. Along with monitoring water quality at the treatment plants, Louisville Water monitors water quality throughout its distribution system. In recent decades, the utility has implemented many voluntary programs to conduct extensive monitoring and provide valuable data that have afforded a clearer picture of water quality in the distribution system.

oto credit]

oto credit] For decades, Louisville Water scientists have researched and carried out methods to optimize treatment specifically to minimize heavy metals in drinking water. This research has helped control pH and alkalinity to prevent corrosion by establishing water quality goals and improving chemical feed selection. Because the noncorrosive water that leaves the utility’s treatment plants is rich in calcium, it forms a calcium precipitate that provides a protective scale layer on the interior of pipes and plumbing fixtures.

Although corrosion control is paramount to minimizing the risks associated with lead in drinking water, removing the lead service lines truly eliminates it. Dissimilar metallic materials often accelerate corrosion through a process known as galvanic corrosion, which can release even higher amounts of metals. At times, Louisville Water has installed dielectric couplings — 2 ft long plastic pipes — as a transition between a public-side copper line and a private-side lead service line to inhibit galvanic corrosion.

A typical service line consists of a public section and a private section. Owned by the water utility, the public section extends from the connecting water main, past the water meter, and to the private property line. The private section, which is owned by the property owner, extends from the property line to the home. This section may be made of lead, galvanized steel, copper, or even possibly plastic material.

The length of the public section varies, depending on the location of the water main. If the water main is installed along the same side of the roadway as the house, the service line could be about 5 to 10 ft long. If the water main is on the opposite side of the roadway from the house and the service line crosses multiple lanes of traffic, the length could exceed 80 ft. Louisville Water installs 0.75 in. diameter copper service lines for typical residential homes, providing a capacity of 20 to 50 gal./min.

In the early 1970s, when the push to replace lead service lines began, the work often was prompted by requests from customers who had leaking service lines or as part of water main replacement projects. For example, any time a crew was dispatched to repair a leaking or broken lead service line, the team replaced the line with a copper version instead of repairing it.

A 1991 field and records survey determined that approximately 36,000 public lead service lines remained in service. To complete the switch to copper service lines, the company created the Main Replacement and Rehabilitation Program. One of the results of this program was the development of a model for replacing water mains. This model is based on a formula that evaluated the age of the pipe, pipe material, and the number of breaks and leaks.

This model compiled multiyear information on main breaks and used main break frequency as a measurement of system performance. The target is to have fewer than 15 breaks per 100 mi of water main per year, or a main break frequency of less than 15. By 1994, 1,900 of Louisville Water’s lead service lines were being replaced annually.

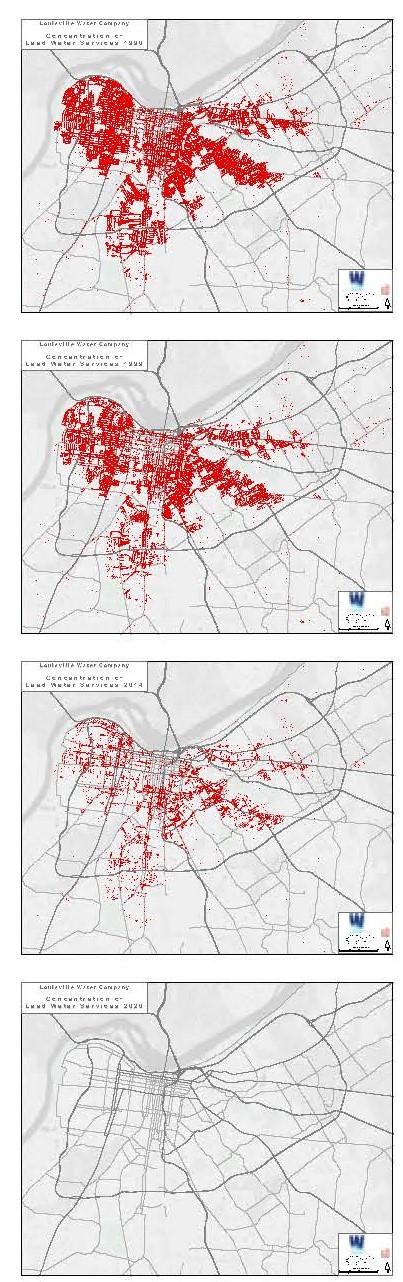

By 2002, with its replacement program well underway, Louisville Water started the Lead Block Replacement Program. The goal is to remove all known lead service lines. Instead of waiting to find the lead service lines as part of the Main Replacement and Rehabilitation Program, utility engineers developed replacement programs starting with neighborhoods known to have high concentrations of lead service lines. With annual budgets ranging from $500,000 to $5 million, these service line renewal projects were run by dedicated project engineers.

Using field records and historical information, staff created a Microsoft Access database to map the location of lead service lines. This database was updated regularly as additional information was gathered by field inspectors checking vaults and by staff reviewing old project files. The database included service lines that were known to be lead or had an unknown material type but were installed before 1937. Anytime contractors or field personnel who were working to replace a lead service line found another lead line in a vault on an adjacent property, that service line was also replaced.

As part of the Lead Block Replacement Program, Louisville Water’s engineering department created and managed projects to replace from 100 to 400 service lines at a time. Each project included a pipeline study map for specific neighborhoods; this provided detailed water facility information, including the location and size of the water main and the locations of valves and service lines as well as project specifications, including addresses, size of service, and an engineer’s cost estimate.

Although Louisville Water crews did some of the work, a large percentage was contracted to outside parties under the utility’s supervision because of the amount of work needed to complete the program and the limited capacity of its internal crews.

Projects were prioritized based on city paving schedules, and work was rotated among neighborhoods so that no one area was overly burdened with construction activity. Before construction began, customers were notified and road closure permits were acquired.

If lead was found on the customer side of the service line, the customer was given the opportunity to replace the line, with Louisville Water agreeing to cover 50 percent of the cost of replacement. If the customer declined, a dielectric coupling was installed at the property connection. Additionally, Louisville Water provided water filter pitchers to customers who had private lead service lines. Following the service line replacement, customers were asked to flush their water lines each morning for five minutes for 30 days to clear out stagnant water that may have picked up residual lead overnight. The company gave credits to customers for the water used in flushing.

By 2015, the known lead service lines were not as concentrated geographically but instead were spread out. As a result, the costs associated with replacing these increased. By 2018, the average cost of replacement had risen to $4,500. Several factors caused the prices to increase. When the replacement work is concentrated in one neighborhood, the cost of mobilization is reduced. Although competitive bidding lowered the replacement price, changes in government requirements led to higher paving and yard restoration costs. To control those, projects were grouped together to attract larger bidding pools.

In most cases, replacing a lead service line became routine: a three- to five-person crew would pull out the old service line and pull through the new one. If landscaping was not involved, a small bulldozer was used to dig a hole at the water main and at the property connection. Then a small directional pneumatic boring tool was used to pull the new service line into position. Hand excavation was also used on the customer side to make the final tie-in. The line was then flushed for 60 minutes and returned to service, and streets and yards were restored.

Obstacles occasionally arose. For example, a crew sometimes had to contend with inadequate soil cover above a water main, increasing the risk associated with installing a new service line in such close proximity to the main. In other cases, crews uncovered trolley tracks or other unexpected utility lines. In each of these situations, the utility paused to confirm the clearances between the existing underground infrastructure and the planned location of the new service line. In some cases, the location of the new service line was moved.

Many beautiful lawns and gardens required hand-digging or vacuum excavations to preserve landscaping or avoid damaging retaining walls. Most customers preferred the use of vacuum extraction for digging holes on their property because of its less intrusive, smaller construction footprint. Some customers have a small retaining wall that adds a unique feature to their property. In such a situation, vacuum excavation enabled the utility to make a smaller hole right at the retaining wall. In this way, a crew could make the service connection while reducing the chance of damaging the wall.

If a retaining wall is damaged, it is very difficult to match the original construction. Therefore, crews were careful to avoid damage in these unique situations. The more difficult replacements included brick roads and floodwalls. On one project involving a water main in a brick street, the brick was removed and reinstalled using a qualified brick pavement installer. On another project, portions of service lines that were to be replaced passed beneath a floodwall that extended more than 500 ft down the middle of a street. The 10 ft tall reinforced-concrete floodwall had been built to protect against flooding from the Ohio River. Rather than constructing the new service lines beneath the structure, the utility added a new water main on the other side of the floodwall. The old service lines were sealed off and abandoned in place.

Along with replacing its lead service lines, Louisville Water created a proactive, voluntary monitoring program within school facilities to establish higher health standards for children. Since the late 1980s, Louisville Water scientists have worked with public school districts and private schools within the utility’s tricounty service area. Schools are provided sampling materials, and personnel are trained on how to collect these samples to test the drinking water.

Louisville Water’s certified laboratory analyzes the samples using EPA method 200.8 (Determination of Trace Elements in Waters and Wastes by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry), which has a detection limit of 0.0010 mg/L for lead. If lead is detected at any individual outlet, school officials are encouraged to carry out several tasks, including conducting an inspection, looking for components that contain lead, performing maintenance, or removing or replacing the fixture or fountain in question. If any work is performed by school facilities, Louisville Water offers free resampling of those outlets to verify that the work successfully reduced lead levels.

The utility has also expanded this free monitoring program to day care centers. Providing instruction and guidance and developing these partnerships have led to a greater awareness of the potential water quality issues that such facilities may face.

As mentioned above, Louisville Water’s responsibility ends at the property line where its service line connects to the customer’s service line. The customer is responsible for maintaining the line that extends from the property line to the home.

Because of its commitment to public health, the company started the Private Lead Service Line Replacement Program in 2017 to assist customers with the removal of their private-side lead service lines. Even though Louisville Water had to replace 74,000 publicly owned lead service lines, there are nowhere near as many privately owned lead service lines needing replacement. In fact, approximately 2 percent of the utility’s 252,000 residential accounts have private lead service lines.

The effort to help customers intensified after Louisville Water completed the removal of its public lead lines because it was able to dedicate resources to focus on notifying and working with customers who have private-side lead service lines.

Utility staff within the engineering, communications, and water quality departments have disseminated information and alerts to customers who may have a private lead service line and offered them financial assistance. Letters and postcards were mailed to customers explaining the process to get financial assistance.

Additionally, customer service employees are trained to answer questions about the program. If they are asked technical questions, the reps transfer the calls to the lead program engineer for additional assistance. Dedicated phone lines and email addresses have been set up for customers to contact the utility. Information is also on Louisville Water’s website. Customers can also request to have their water tested for lead as part of a free service offered by the utility.

Because replacing a private-side service line can be expensive, Louisville Water will pay 50 percent of the cost, up to $1,500. To obtain this funding, customers first must get quotes from two licensed plumbers willing to perform the work, a measure that helps ensure competitive pricing. Customers then send the quotes to Louisville Water for its approval, and the utility chooses one of the plumbers.

After the new private service line is installed, an inspector from Louisville Water flushes the line for 60 minutes. The inspector also sends information about the new private service line to the utility’s geographic information systems department, which then updates the records. For customers who cannot afford this upgrade and meet eligibility requirements, a grant program administered by the Louisville Water Foundation — the charitable arm of the utility — may pay the remaining replacement cost.

Private galvanized lines, which can hold lead particles that enter them, have now been added to the program if records indicate that they were once connected to lead service lines. Even though a lead line has been removed, lead particles inside a galvanized line can leach lead into water. Removing galvanized lines also reduces the likelihood of galvanic corrosion.

Louisville Water began with 800 customers whose utility records indicated they had a private lead service line. In the first few months, this effort has had limited success, with fewer than 10 customers participating in the program. Economic hardship resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of interest on the part of some homeowners in replacing their service lines are the most common obstacles. The utility has found social media to be a good way to get information to the general public. Plans are in motion to reevaluate how the utility communicates this program to customers.

It is important to communicate the science and research behind maintaining excellent water quality at the treatment plant as well as what customers can do to maintain this quality within their homes and businesses. Stagnant water can degrade water quality, so maintaining high-quality water requires making sure water is regularly used or implementing proper flushing practices. Louisville Water’s website contains a “Lead Awareness” page that offers information related to lead in drinking water, instructional videos, and resource links for additional information.

In the 1990s, Louisville Water created an internal “lead team” that met regularly to document line locations, work procedures, treatment optimizations, water quality monitoring, customer questions and issues, and communication tactics. Members of the team now include staff from the treatment plants, distribution water quality, water quality compliance and research, customer service, distribution operations, geographic information systems, communications, and engineering. The water quality staff members assist with water quality issues surrounding sampling and results, while engineering staffers help customers with replacement cost estimates, contractor selection, and construction issues.

The team’s work has led to a companywide understanding of the Lead Block Replacement Program and built on the history of advancing public health. Today, the team continues to meet and is focused on the private-side program, with the end goal of assisting and encouraging customers to remove all their known lead and galvanized lines.

Although Louisville Water invests substantial effort communicating directly with customers known to have private lead or galvanized service lines, a significant number of customers have unknown or unidentified service line materials. The website and social media platforms provide information to a broader audience and will help identify customers with unknown materials. Information is still mailed to customers.

Beyond the customers, Louisville Water focuses its outreach efforts on a long list of stakeholders, including elected leaders, the Louisville Metro Public Health Department, social service agencies, plumbing contractors, and the Kentucky Division of Water. The outreach extends to conversations with the local health department and medical community, elected officials, and leaders of local schools and child care centers.

Until the lead crisis in Flint, Michigan, emerged, the communications strategy focused on the customer, employees, and those key stakeholders mentioned above. Reporters might have raised the issue, but the utility was not proactively — or publicly — addressing the topic of lead. This approach changed in 2016, when Louisville Water launched a public-facing campaign with media events, stories about the lead service line replacement program, the private-side assistance, and the overall quality of Louisville’s drinking water.

Although the ongoing pandemic has prevented a large-scale media event to announce the completion of the work to remove its known lead lines, a video created to tell the story quickly reached more than a million people in just a few hours.

Much of Louisville Water’s success in achieving its milestone comes from the collaboration and commitment that have evolved over decades. Today, employees frequently work with other water utilities to develop treatment and monitoring strategies, replacement programs, customer communications, and public outreach. Scientists at the utility continue their research, even working on patented technologies to reduce levels of lead in drinking water fountains. Because schools and child care facilities often lack funding to address problems pertaining to lead in drinking water, identifying cost-effective solutions for these customers while reducing children’s potential exposure to lead is a win-win.

The organization’s three-pronged strategy for addressing lead by optimizing water quality and treatment, replacing lead and galvanized service lines, and educating the public has improved public health. In October, Louisville Water marked its 160th anniversary of delivering water. Along with this milestone, customers of the utility can take pride in the quality, innovation, and value that go into every glass of drinking water.

This article first appeared in the December 2020 issue of Civil Engineering as "Lead-Free in Louisville."