By Jared Brey

A grand experiment fusing design, engineering, technology, and natural processes could soon emerge in a remote part of the Gobi desert in Inner Mongolia in the unlikely form of a proving ground for new-model cars.

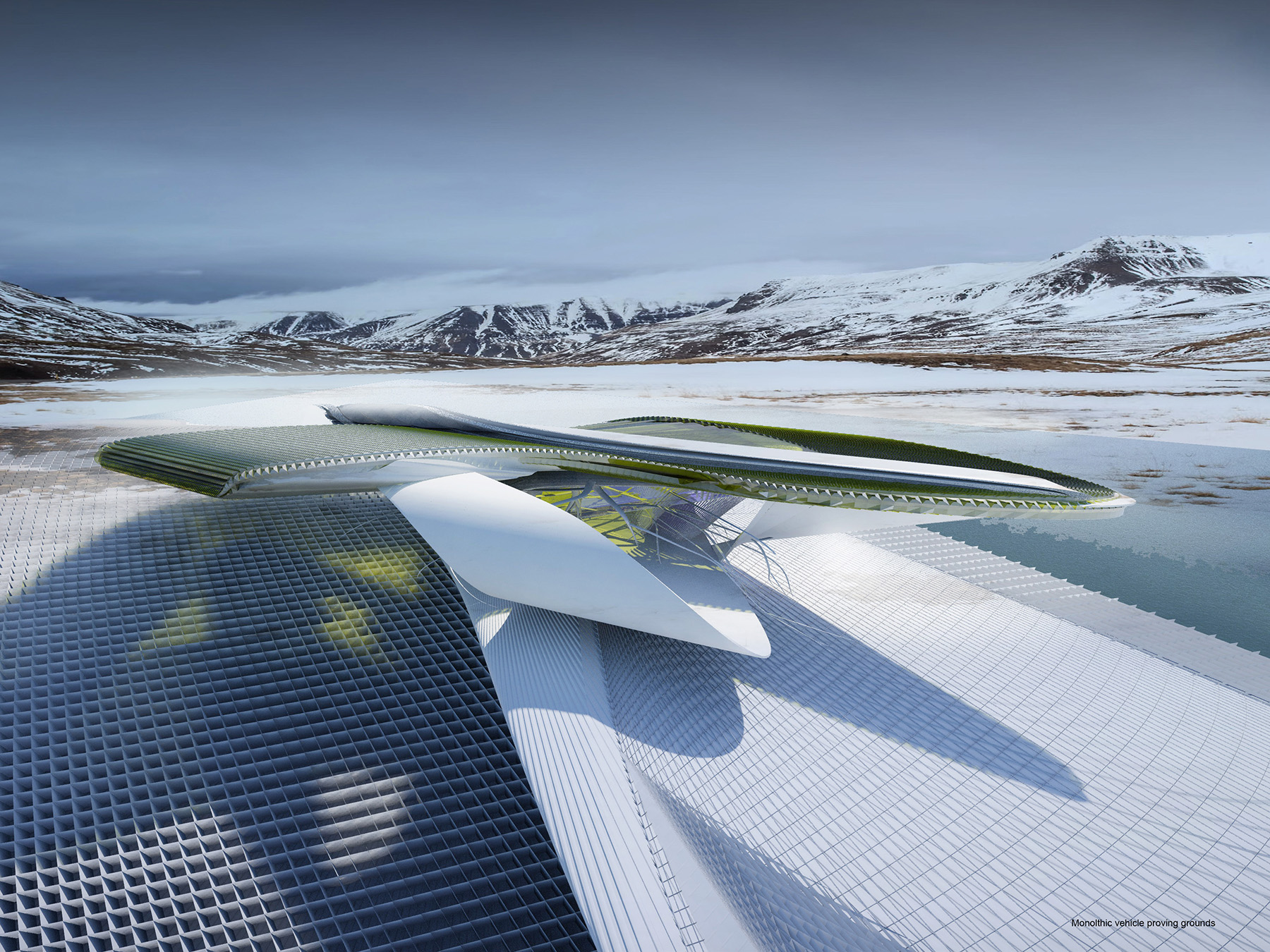

The Sand Drift Proving Ground is designed by Margot Krasojević Architects, a design studio based in London and Beijing, on behalf of a Chinese car producer. The proving ground will test the performance of new models on a variety of changeable, artificial surfaces, including “potholes, deep sand pits, gravel, rumble strips, sine waves, undulating asphalt, and cobblestoned road sections,” according to promotional materials. Part building and part landscape, it is designed to appear as if it was blown onto the site by the wind.

Electrical engineers and physicists contributed to the design of the proving ground. The primary structure is a concrete, double-barrel vault that sits partially within the desert rock. A cantilevered ramp, or looped track, projects from and circles the building. Aided by hydraulics, the ramp can “slide into the landscape” to change the gradient or conditions of the track (such as flooding and freezing), according to press materials.

Within the looped track are expansion sections “lined with (carbon) fiber-reinforced polymer composites, within which piezoelectric cells are attached,” Margot Krasojević explains. These piezoelectric sensors can be activated to create the different driving conditions. The looped track projects over a hydroplane area. The length of the track can be observed — and filmed — from a viewing gallery in tunnels connected to the building.

The building is engineered to partly freeze and thaw, both responding to environmental conditions and creating artificial conditions. It can also power down when not in use, Krasojević says. The building goes “dormant” during periods of inactivity, with electronic features that allow it to protect itself from dust and temperature cracks amid the wild swings of the desert climate. It is “activated” using motion sensors that respond to the presence of a test vehicle.

“The building behaves as if on a remote ventilator with minimum input from management,” she says.

Krasojević has previously created designs for a beach house partly powered by wave energy and a Self-Excavation Hurricane House that responds to intense wind speeds by burying itself for protection. She designed the proving ground to appear as a monolith hidden in the desert rock, “awaiting discovery.” With high-concept, high-tech designs like that, she says, there’s often a leap of faith that’s required to move from computer modeling and virtual simulation to the real world.

“I find that with most experimental design, there is an element of overlooking potential derailment and flaws,” she says. “Within reason.”

Jared Brey is a reporter based in Philadelphia.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2023 issue of Civil Engineering as “With the Wind.”