By Robert L. Reid

New York City’s Bluebelt program combines natural systems with “gray” infrastructure to reduce flooding and improve water quality.

On New York City’s Staten Island, civil engineers, urban planners, and various water experts have created an innovative, nature-based stormwater management system that combines existing wetlands, streams, creeks, and ponds with current and newly constructed water conveyance infrastructure.

Dubbed Bluebelts, the natural features work together with the so-called gray infrastructure of concrete pipes, weirs, and other structures “to reduce the risk of flooding, control erosion, and improve water quality,” according to the ASCE Innovation in Sustainable Civil Engineering Award that the project received in October 2024.

Dating to the mid-1990s, the Bluebelt program “has become one of the city’s great success stories for managing stormwater,” said Rohit T. Aggarwala, New York City chief climate officer and commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, which developed the Bluebelt system.

Beginning borough

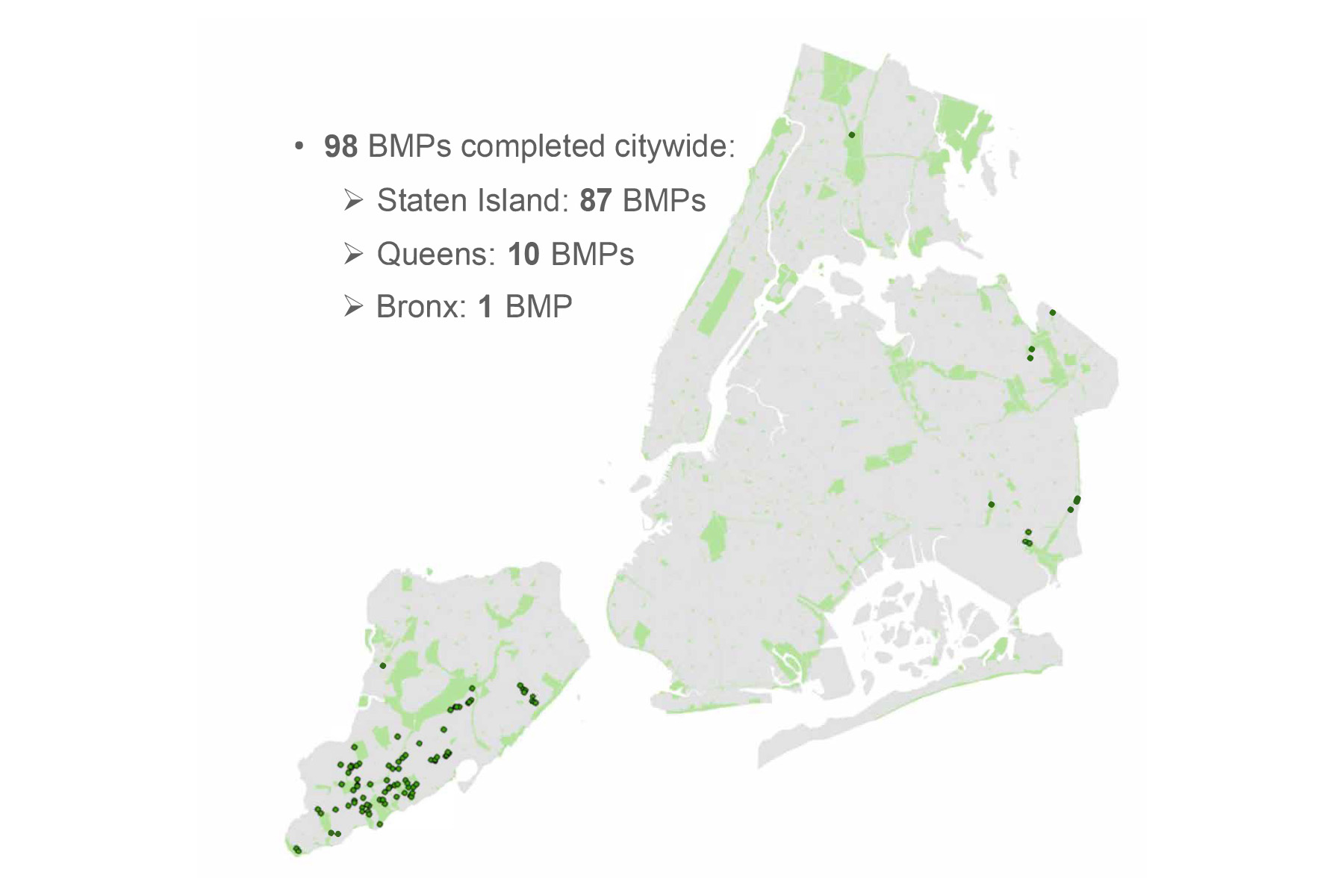

At press time, the program had just completed work on its 98th Bluebelt project, 87 of them on Staten Island. But the program is also expanding to New York City’s other boroughs, with 10 in Queens and one in the Bronx so far, said Sangamithra Iyer, P.E., the NYCDEP’s chief of Bluebelts and urban stormwater planning.

Ironically, the reason why Staten Island was the first place to benefit from the new Bluebelt system is because it was the last borough in New York City to get a modern sewer and drainage network, noted Iyer. More rural than other parts of New York City, Staten Island had featured small communities and large open spaces, including freshwater wetlands.

Following the construction of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge in 1964, however, the population on the island began to increase and eventually outpaced the city’s ability to install new sewer lines. So developers installed mostly septic tank systems, said Dahlia Thompson, P.E., an associate vice president at Hazen and Sawyer, the engineering firm that assisted the NYCDEP in designing and implementing the Bluebelt system.

Staten Island’s growing need for sewers and stormwater management, however, coincided with greater environmental protection for wetland areas by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and other regulatory bodies. Thus, it was increasingly difficult to put in a traditional network of sewer pipes “that would go through critical wetland areas,” said Iyer.

By the late 1980s, therefore, key locations on Staten Island were “suffering from regular flooding as well as poor water quality in the streams due to failing septic systems,” noted Thompson in the 2022 article “The Staten Island Bluebelt: 20 Years Later,” which she wrote for Hazen and Sawyer’s website. And the problem was only growing more complicated, because while sanitary sewers would damage the freshwater wetlands, diverting stormwater away from the wetlands would drain those areas permanently, she explained.

This complex combination of challenges required a novel combination of solutions, which the NYCDEP and Hazen and Sawyer ultimately devised. A key part of the plan involved working with the region’s natural features rather than destroying them — leveraging the existing wetlands so they could “do what nature intended them to do: store and filter and convey water,” noted Iyer.

The approach reminded her of a quote from novelist Toni Morrison: that water has “perfect memory” of where it once flowed and thus will always want to flow there again. So while the plan involved the installation of new pipes and other concrete components, those constructed elements were designed to feed stormwater into the existing wetlands, streams, and other water sources and work to restore natural drainage corridors, Iyer explained.

Sanitary sewers would be constructed as a separate system but designed to divert sewage around the watershed’s open spaces and wetlands to preserve those natural features as much as possible. The installation of sanitary sewers also allowed homes to eliminate the use of septic systems, thereby improving water quality in the adjacent water bodies, noted Thompson.

Water and wildlife

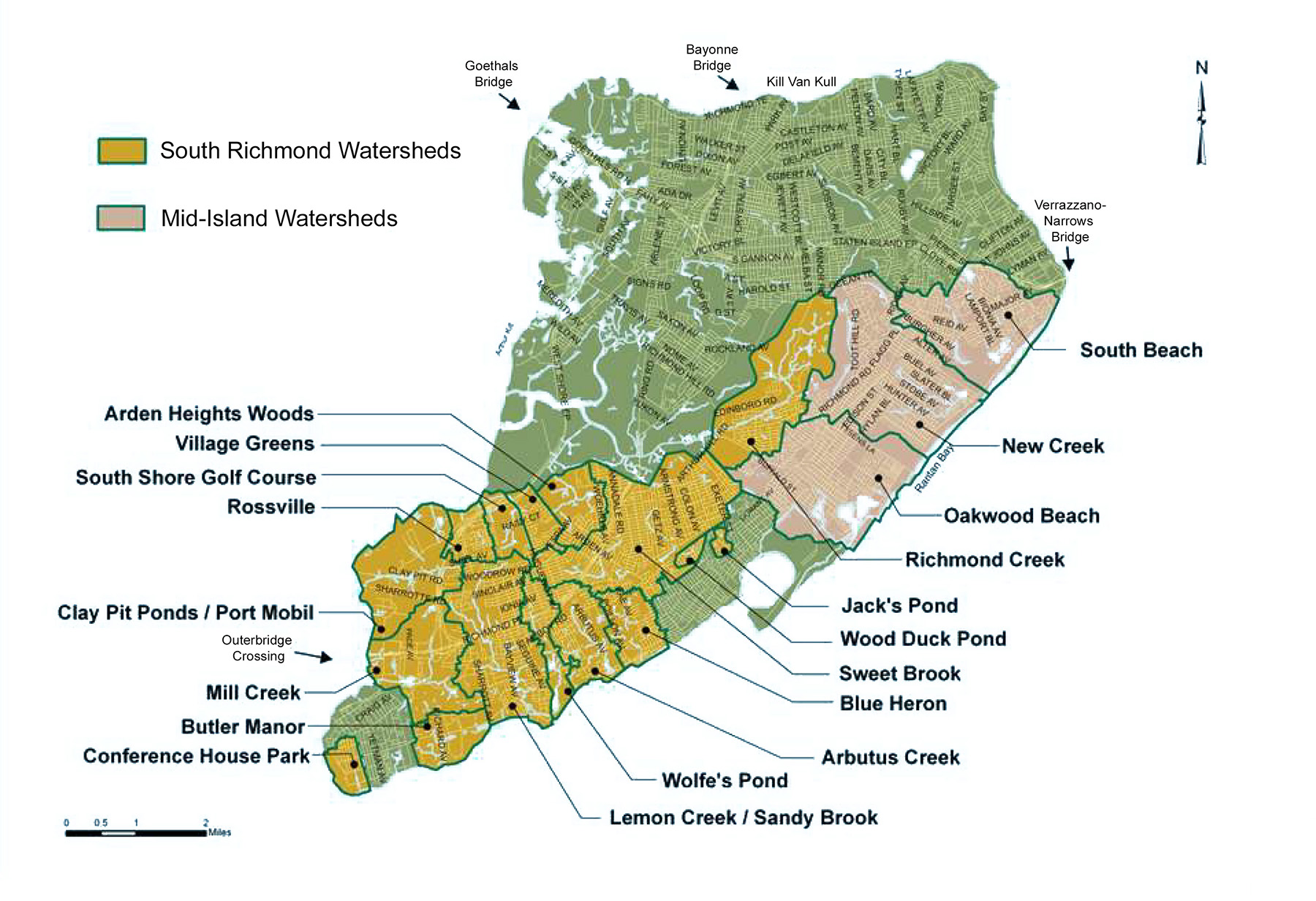

The result has been the Bluebelts, a name derived from the fact that the first projects were constructed in proximity to Staten Island’s Greenbelt system, a corridor of preserved, open green spaces, said Iyer. Intended to create a similar corridor for drainage, the Bluebelts represent “a series of ecologically rich stormwater best management practices” that not only help prevent and alleviate flooding but also provide additional benefits in terms of open spaces and wildlife habitats, Iyer explained.

In August 2021, for example, the NYCDEP announced in a press release the completion of three new Bluebelt projects along the South Shore of Staten Island. Costing more than $135 million, these projects upgraded drainage to reduce flooding in the neighborhoods of Tottenville, Eltingville, and Great Kills.

In Tottenville, more than 8,200 linear ft of new storm sewers were installed, along with 90 new catch basins, plus holding ponds. Together, these components created the 4.4-acre Mill Creek Bluebelt out of what had been a “swampy marshland filled with debris” and an invasive perennial grass known as Phragmite, according to the 2021 NYCDEP press release. The Mill Creek Bluebelt “will hold and naturally filter the stormwater before it eventually drains into the Arthur Kill,” the agency explained.

A new gravel walkway meanders through this Bluebelt area, which was planted with some 12,200 native wildflowers and other plants, as well as 240 shrubs. More than 100 new trees were also planted throughout the project area, and sidewalks, roads, and curbs were rebuilt or widened to improve pedestrian and traffic flow in the area.

In addition, more than 11,600 linear ft of new sanitary sewers were constructed. These features enabled 210 homes “to connect to the city’s sewer system and discontinue the use of septic tanks,” the NYCDEP noted in the release.

To improve the quality of drinking water, the Tottenville project also featured the installation of more than 12,400 linear ft of new water mains, which were made from concrete-lined ductile iron and replaced older cast iron pipes, which had been prone to breakage.

Similar new gray infrastructure and other improvements were made in the Great Kills and Eltingville areas. In particular, years of accumulated sediment was removed from a Great Kills pond to increase its water storage capacity, thousands of native wetland plants were added to naturally treat the pond water and prevent algae blooms, and a solar-powered aerator was installed to oxygenate the water. Because of these measures, the project team could also stock the restored pond with hundreds of largemouth bass and other native fish.

Common features

At the start of the Bluebelt program, in the South Richmond area of Staten Island, some of the existing wetlands were “pretty degraded,” noted Iyer. So one of the first steps involved restoring and expanding the historical water conveyance corridors. New York City also had to determine which properties that could potentially become a Bluebelt were already owned by the city and which would have to be acquired, said Thompson. The goal was to use vacant land, she added, so that no one would have to leave their property.

Likewise, the city did not want to alienate the public by taking land that was already in use, such as for a playground, and turning it into a wetland, Thompson noted. And because many of the Bluebelt sites are on low-lying land adjacent to occupied areas, the city had to be careful about issues such as grading to be sure to protect private property. In particular, flat, low-lying areas can require large pipes installed at a shallow depth that can conflict with other underground utilities, Thompson said.

The Bluebelt projects typically encompass about 1 or 2 acres, with the largest reaching roughly 12 acres, noted Robert Brauman, CPESC, the deputy chief of operations for the Bluebelt program. The drainage plan for a Bluebelt project will generally combine multiple features, including an extended detention basin for stormwater storage and filtration, with an inlet to capture sediment; a micropool to prevent outlet structures from clogging; and the seeding of native plants, shrubs, and trees.

A Bluebelt site might also include sand filters, an outlet stilling basin to attenuate water velocity, the retrofit of an existing pond or enhancement of a wetland, the reconstruction of an existing culvert, and the restoration of a stream, among other components.

If an existing lake is incorporated into a Bluebelt project, the NYCDEP might add a new weir to better control the flow of water into or out of the lake, said Brauman. Or an existing culvert that is undersized might need to be enlarged and enhanced with other new features, such as a natural bottom of stone rather than just concrete.

A stone bottom better mimics a natural streambed.

The design of Bluebelt infrastructure also considers aesthetic features that link the new projects to Staten Island’s agrarian past, said Brauman. This includes the use of stone facing on the concrete headwalls of extended detention basins and other structures.

“At the start of our program,” Brauman explained, “we visited various local museums on Staten Island and examined old photographs of farmhouses and stone walls, and we used those as the basis for our standard details” on the Bluebelt components.

The stonework is “something the community likes, and it helps people identify the Bluebelts across the island,” he noted.

Although the project initially used stone sourced solely from Staten Island, the volumes of stone required eventually forced the NYCDEP to source material from quarries in other locations within lower New York State as well as New Jersey, Brauman said.

In addition to its aesthetic appeal, the stone also makes the Bluebelt structures more resistant to graffiti than concrete, added Thompson.

Public opinion

During the initial introduction of Bluebelt projects, the public often opposed this new and strange approach to flood control, noted Thompson. But then a large storm hit an area with a newly constructed Bluebelt — a low-lying area that had often flooded in the past. “The locals went out to monitor this area” and saw that it had not flooded this time, said Thompson. “After that, the community was much more welcoming.” Thompson added that people even began to ask: “When will we get our Bluebelt?”

Regular maintenance — from cleaning trash racks and testing valves to controlling vegetation — is essential to proper functioning of the Bluebelts, Brauman noted. That’s why the program has an 18-person maintenance staff that visits the system’s sites on an ongoing basis. But working with the public and other organizations has also been a key part of the Bluebelt effort. This includes things like the Adopt a Bluebelt program, modeled after adopt-a-highway programs, in which individuals, schools, and other community groups can volunteer to perform basic maintenance and cleanup activities such as picking up litter or weeding.

“My phone rings off the hook weekly from people looking for sites” where they can volunteer, said Brauman. “It gives people a sense of ownership and buy-in.”

The Bluebelt program also partners with schools, scouting groups, and others on so-called “citizen science projects” that involve monitoring the migration of baby eels in the spring. Each year, thousands of juvenile glass eels swim from where they were born in the saltwater ocean, sometimes thousands of miles away, to now spend much of their lives in the freshwater creeks within the Bluebelt region, Brauman explained.

Previously, the eels and other aquatic life had not been able to access or thrive in certain areas within a Bluebelt region because of bacterial pollution from failing septic systems. But that has now changed following the improvements in water quality thanks to the Bluebelt program, as well as the construction of “natural fish ladders” that feature a series of successive pools using natural boulders and stone that enable the water life to rest before continuing upstream, Brauman stated.

Changing challenges

Looking ahead, the Bluebelt program is working with the Corps on how to incorporate a Bluebelt system into a seawall that is planned for the South Beach region of Staten Island. The most recent Bluebelt projects were designed with climate change in mind, and all future efforts are also being designed that way, noted Brauman. This involves features such as upsized culverts and larger extended detention basins, as well as valves and weir plates that can be adjusted to store more water than originally intended.

The program has also begun including a feature known as full-spectrum detention, which involves a complex series of drainage pipes, each set at a different elevation. “When there’s a big storm event, rather than sending all the water through one pipe of a certain size, we can send it down in a more finessed way with 10 to 12 pipes ... to fine-tune the stormwater flow,” Brauman explained.

Such efforts mean that “we won’t have to go back in 20 or 30 years with a new capital budget to modify structures,” Brauman said. “Instead, we’ve already built in for future larger storm events.”

As the Bluebelt program expands, the NYCDEP is working with the engineering firm Dewberry on some of the new challenges these future ventures will involve. For one thing, the Staten Island projects created separate sewer and stormwater systems, but the work in other boroughs will often encounter combined systems, according to Rahul Parab, P.E., BC.WRE, CFM, M.ASCE, an associate vice president and deputy manager of Dewberry’s water group as well as the firm’s national flood resilience engineering practice leader.

When designing new Bluebelt projects, Dewberry’s goal will be to somehow separate out portions of these combined systems to have a dedicated stormwater drainage network that flows into the Bluebelts, perhaps by repurposing parts of the existing system, Parab noted. But this will not be possible at every site, he added, “so we’ll have to figure out the best way to integrate these complex systems and still have a functional and reliable Bluebelt.”

Other challenges include the fact that some of the sites in other boroughs have historically been streams but have long since been filled in. “So we will need to daylight them and restore the original water systems,” Parab said. Because other boroughs are also more heavily developed and populated, the new sites will likely be more tightly constrained than the Staten Island projects.

Parab also anticipates needing to raise the roads in some locations to install the gray infrastructure to connect into a new Bluebelt, as well as designing coastal outlet control structures to accommodate future tidal conditions and sea-level rise.

From hydraulic “memory” to the threats of more intensive storms and floods, the Bluebelt system has proved to be an ingenious, adaptable, and sustainable solution that works with nature — even in an urban setting — to keep water flowing in the right direction.

Robert L. Reid is the senior editor and features manager of Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2026 issue of Civil Engineering as “Hydraulic Memory.”