Oregon Department of Transportation

Oregon Department of Transportation This is the second in a two-part Trending in the Industry series looking at autonomous vehicles and their future. Check out the first installment here.

Autonomous vehicles aren’t going away.

From autonomous taxis to interstate trucking, there is an abundance of opportunities for AVs to fill transportation needs in a safe way (Waymo reports that its vehicles cause 90% less “serious injury or worse crashes” and 81% fewer “injury-causing crashes”) without compromising effectiveness.

But even outside of the more obvious issues – AVs consistently underperform in severe weather conditions like heavy rain or snow – there are challenges with how existing roadway technology is able to handle these vehicles.

And inconsistent federal, state, and local regulations as well as AV skepticism make it even harder to determine when they can reach their full potential.

A league of their own?

Unlike human drivers, AVs are predictable.

“When we drive, we wander basically all over the road,” said Tom Fisher, a professor of architecture at the University of Minnesota and director of the Minnesota Design Center. “Autonomous vehicles are operated by GPS, and they're very precise. They tend to follow the same path over and over again.”

And this consistency could cause wear and tear on the roads.

A Federal Highway Administration study found that “decreased wheel wander and increased lane capacity” with AV use could increase the rutting potential of a roadway in certain traffic conditions. The study noted that higher traffic speeds would minimize this rutting effect. A later study found similar results but did not account for mixed-traffic scenarios.

Ruts can make steering more challenging and increase the potential for hydroplaning, even for AVs. Although there are solutions to this problem, they would require major infrastructure updates.

“We envision a future in which our roads will be more like a railroad track, with reinforced-concrete-grade beams that can take repetitive wear of the of the tires of the vehicles, which then allows the rest of the street to be pervious,” Fisher said.

Changing road designs impacts water and sewer systems and other aspects of infrastructure, and Fisher thinks that the capacity to make these changes is something that lies further in the future.

“I don't think we’re yet focusing enough on the infrastructure impacts of autonomous vehicles,” he said. “We’re still somewhat fascinated by the vehicles themselves without realizing that the infrastructure will likely change simply because you can’t have rutted roads.”

The AV industry has brushed aside the potential necessity of even minor infrastructure changes for the successful integration of these vehicles, noted Shane McKenzie, P.E., M.ASCE, connected and automated vehicle technology lead for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet.

“The industry says they do not need anything; they are developing technology to navigate existing infrastructure,” she said. “Observers recognize they travel in a predetermined driving domain.

“Others look at the development thus far and recognize the opportunity to put automated driving system equipped vehicles in the same lane to optimize safety, efficiency, and throughput,” she continued.

Blaine Leonard, P.E., BC.GE, Pres.10.ASCE, a transportation technology engineer at the Utah Department of Transportation, said that there is no choice but for infrastructure to be ready now because AVs “are coming anyway.”

“It would be nice if we did a better job with things like paint striping,” he said. “It would be nice if you and I as humans would park our vehicles in a way that they don’t protrude into traffic lanes. … That really screws up automated vehicles.”

But inconsistent policies across the country make it hard for regulators to come to a consensus on both AV infrastructure and the vehicles themselves.

Policy jumble poses challenges

Vehicle policies and traffic laws already vary across state lines and even in municipalities in the same state, where, for example, one may outlaw right turns on red, while others allow them.

And even neighboring states can have vastly different levels of enforcement or penalties for the same traffic infraction.

With AVs, these differences become even trickier.

“There are certain states that have been very intentional in terms of making it favorable for vehicles or AV manufacturers and operators to be able to implement their technology on the road, like Texas, Arizona, and California,” said Loren Stowe, a certified functional safety engineer and senior research associate at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute.

But in the Northeast, where travelers cross state lines more frequently, differences in AV regulations could become more apparent as new policies are created.

“What do you do when you cross the bridge from New York City to New Jersey? Are the requirements the same?” said Stowe. “If not, then the manufacturer’s going to have to make sure that they comply with both sets of regulations and rules.”

McKenzie cited, for example, New York’s unique law requiring drivers to have at least one hand on the steering wheel when driving, a requirement that “conflicts directly with (automated driving system) operation.

“Ultimately, laws across neighboring states will need to become interoperable to support safe and seamless ADS deployment,” McKenzie said.

Despite this law, New York City does offer testing permits for autonomous vehicles. And Waymo received one in February 2025.

With the permit, Waymo is able to test eight vehicles in parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn through March 31, 2026, with a test vehicle operator present.

But due to pushback from New York’s taxi industry, it is unclear whether Waymo will actually make its way into the city.

Removing a human driver also challenges the existing method of issuing driver’s licenses, which is currently left up to the states.

“I get my driver’s license from the state in which I reside. Well, how does that work for an AV when the licensed driver is no longer performing the driving task?” said Stowe. “The driver is no longer a human in the driver’s seat of that vehicle. The driver is an agent that was created by the manufacturer.”

When the driver shifts to a single entity, who provides the license becomes a question that hasn’t been solved.

“Is it the federal government? Is it the states? Is it some agreement across states as to what that will be? So, that becomes an interesting discussion,” Stowe said.

And the industry “is largely arguing that we need consistency, and therefore, the federal government should step in and create rules around AVs,” Leonard said.

“Many of the state laws say you can operate these, but you have to have a permit, or you have to demonstrate to us that they’re safe, have extra insurance, or post extra bonds,” he said. “So, the range of regulations in the United States runs from the incredibly permissive like Utah, the incredibly regulatory like California, and everything in between.”

To date, 26 states have passed laws approving the operation of AVs. Despite nearly half of U.S. states leaving AV policy unclear, there are currently no laws banning them.

Kentucky passed legislation allowing self-driving vehicles to operate in July 2024. But critics of the legislation have pointed out that self-driving semitrucks might not be able to take on some tasks performed by truckers on interstate-scale trips, where a human is required to change axle configurations to meet the varying requirements when crossing state lines.

Touted by autonomous trucking companies as a solution to workforce gaps, self-driving trucks might have a way to go before breaking through evolving AV policies.

Federal AV legislation is also murky.

Despite variety among state laws, there are certain safety standards – the presence of a steering wheel, pedals, and mirrors – that federal law requires in all vehicles. But governed by sensors, AVs don’t necessarily need these features.

9yz

9yz Federal law currently allows exemptions for 2,500 vehicles per manufacturer.

Stowe said that although this small number isn’t currently a major issue, manufacturers could question its impact on sales as driverless vehicles become more common.

And that conversation is starting to pick up.

“At the start of this administration, there was a request by industry to provide additional opportunities to be able to not necessarily get around the regulations, but to be able to demonstrate that their vehicle is safe, even though it may not comply with the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards as currently written,” Stowe said.

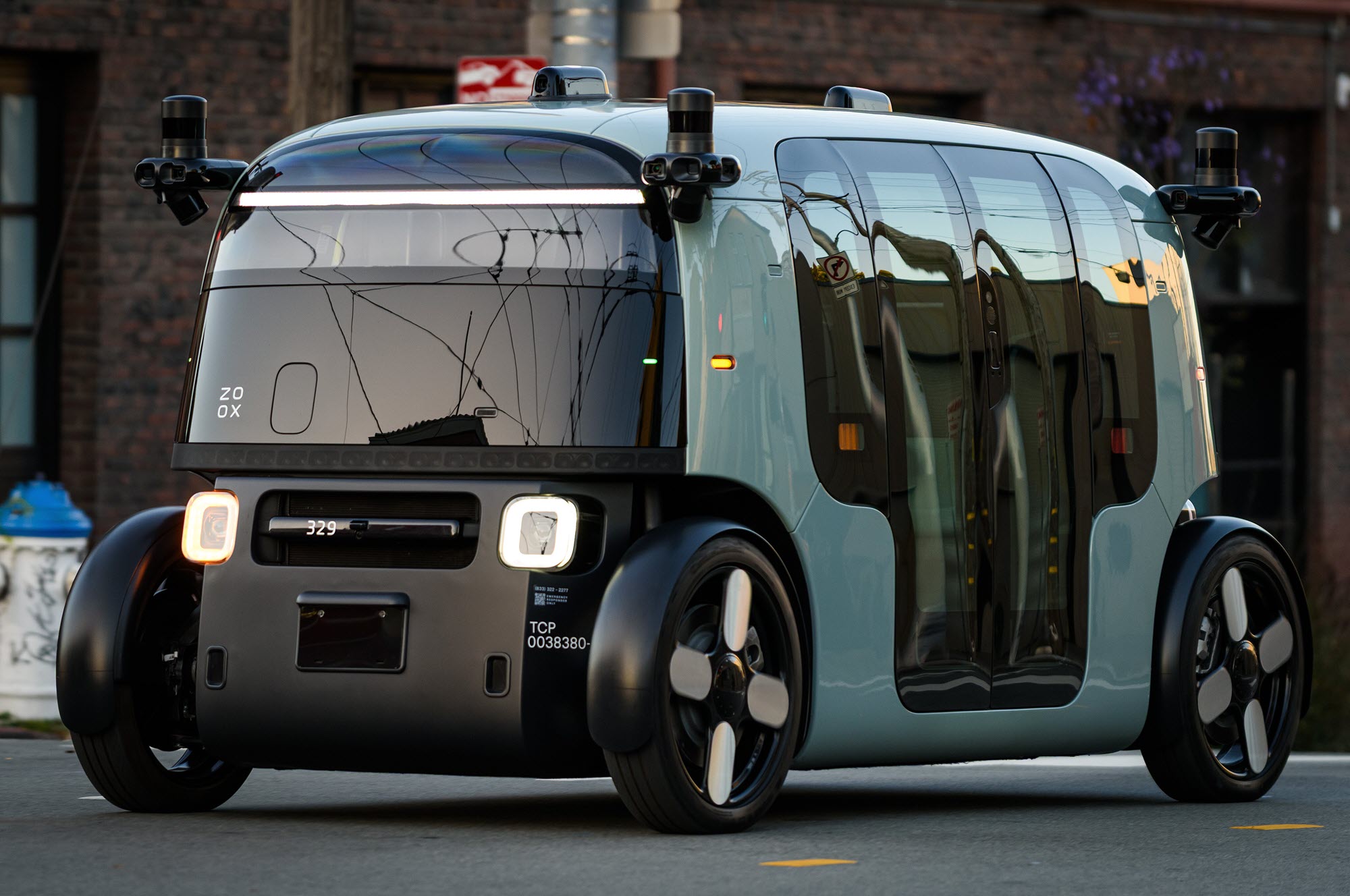

Although Waymo’s vehicles do include these required features, other companies, like Amazon’s Zoox robotaxi service, want to leave them out of their designs. And in August 2025, the company received an exemption from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

What’s next for AV policy?

There is still a long way to go before the federal government, states, and municipalities reach an agreement on how exactly AVs should be regulated.

But Fisher believes there will be a tipping point where skepticism begins to subside.

“Eventually regulators, municipalities, and state governments are going to realize that overly regulating a safe technology doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said.

Although federal progress is slow, the U.S. Department of Transportation is on board with AVs.

In April 2025, the department announced a new AV framework that begins with modernizing Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards to better accommodate driverless vehicle technology.

And in the short term, the DOT wants to expand and streamline NHTSA’s exemption approval process.