By Leslie Nemo

Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English colony in what ultimately became the United States, is an increasingly soggy, flooded space. To preserve the remains of this important historical site, which is on a low-lying 1,500-acre island in the James River, engineers and conservationists are first tackling one of the oldest guards against unwanted water that the former colony has: its sea wall.

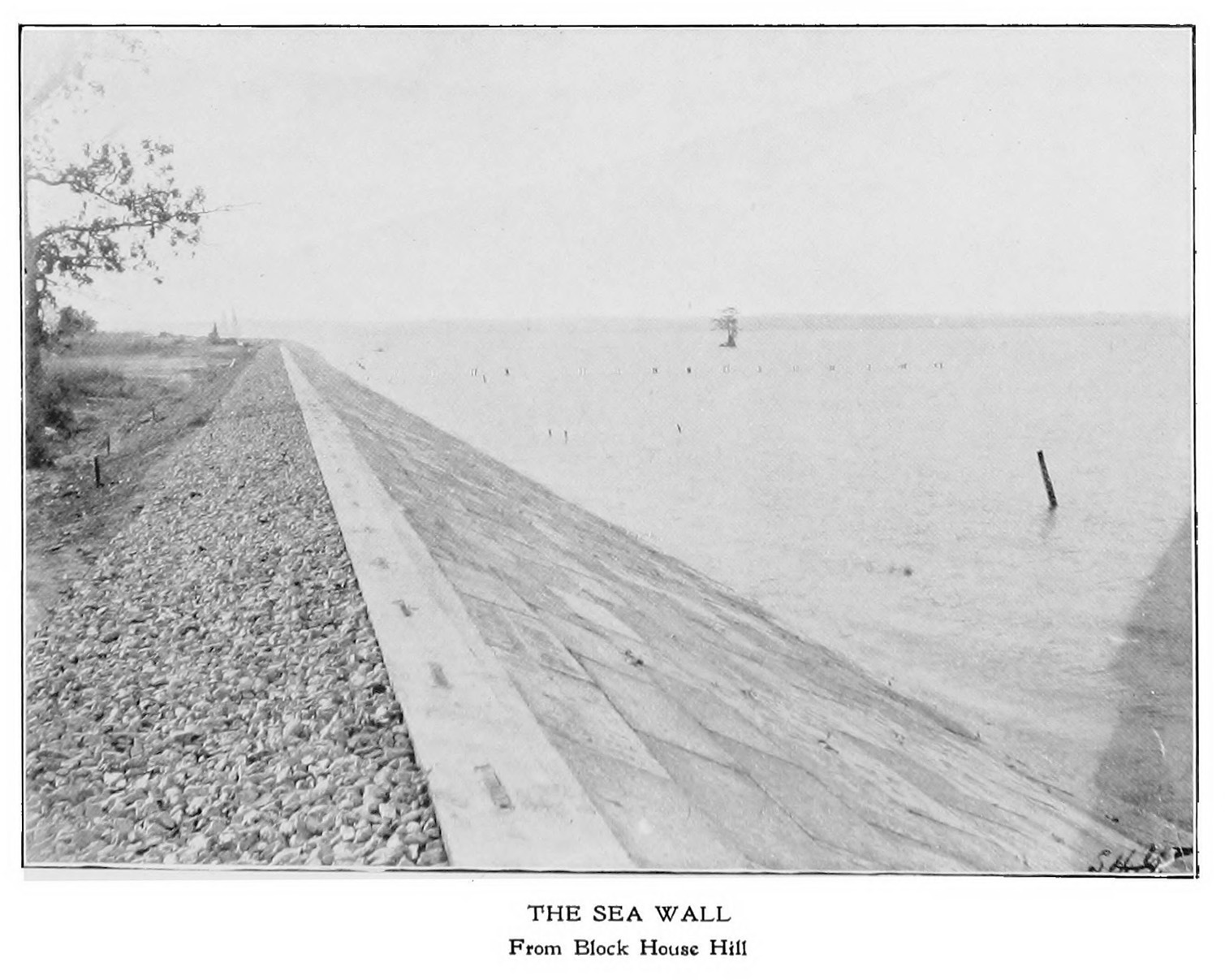

This dirt berm protected with concrete slabs is 1,700 ft long, protects the southwestern corner of the island, and was completed in the early 20th century by the Army Corps of Engineers. Spot-repair maintenance on the wall has kept it in good shape over the years. But with more than $2 million in grant money, the nonprofit Preservation Virginia wants to address multiple vulnerable portions of the wall and give it an extra bit of support against the James River. The work was being finalized at the end of June — and it’s only the first phase of what will have to be a wider, more expensive plan to protect the area from the increased flooding brought by climate change.

Future conditions on the low-lying island are so dire that the site made the National Trust for Historic Preservation list of most endangered historic places in 2022. “There are absolutely plenty of archaeology sites that are going underwater,” says Mike Lavin, the director of collections at Historic Jamestowne, the archaeological group working on the site. “But not many that need to do as drastic of an intervention as we're proposing.”

Jamestown is most famous as the first permanent English settlement in North America and the colony of Virginia is infamous as the location where in 1619 the first enslaved Africans arrived in the United States’ original 13 colonies. Indigenous Americans had already been living in what’s now known as Virginia for 12,000 years before the colonizers arrived.

Care of the site and all the artifacts it contains is split by the National Park Service and Preservation Virginia, which has overseen a handful of historic sites in the area for the past century. For Jamestown, the latter organization often removes topsoil, maps and documents the artifacts and structures that still sit in the ground, and then lays down a protective fabric before replacing the original soil so that archaeologists can return later for a more thorough examination.

An artifact protecting artifacts

Preservation Virginia also maintains the sea wall. As the story goes, the organization requested that the Corps install the wall because of complaints about erosion on the island — specifically, that human remains were appearing as soil washed away. A few years of work resulted in a dirt berm armored with concrete slabs facing outward, each about 8 in. thick, 18 in. long, and 4 ft wide.

Considering its century-plus age, the sea wall is doing well. “They’ve done a great job of maintaining the structure,” says Neville Reynolds, a senior principal and environmental services leader with Vanasse Hangen Brustlin Inc., the civil engineering firm that is handling design engineering for the project. But nearly 120 years of acting as a buffer between land and water has naturally created some weak points.

Storm pressure from waves has shoved water into the cracks between the concrete slabs and eroded the sediment behind. The structural problems only became visible once waves knocked some of the slabs into the growing holes behind them, a process that accelerated quickly. “Once you get a void in between a couple of them, it just makes it worse,” Reynolds says.

The integrity of the wall was struggling in less visible ways too. Preservation Virginia purchased ground-penetrating radar for concrete inspection, and Dave Givens, the director of archaeology at the organization, earned a concrete examination certification so that the organization could look at what was happening behind the sea wall surface. The radar showed where gaps had formed inside the wall in places where the exterior hadn’t yet been displaced. The holes likely stemmed from moisture accumulating on land in places that previously were typically dry — growing water pressure shifted internal portions of the sea wall, leaving it vulnerable in spots to further movement.

No matter the cause of the damage, the solution the project partners have put together is relatively similar. In places where sections of the wall have collapsed due to erosion or where depressions have appeared internally, the team will redo the subgrade and then replace the concrete surface slabs.

The team also installed a revetment that stretches halfway up the face of the existing sea wall. The granite chunks, pieced together, create a rugged surface that will break the waves in place of the original sea wall itself, taking pressure off the underlying structure. “In terms of its construction, it’s pretty cut and dried,” says Richard Gunn, the project manager with Coastal Design & Construction, a Virginia-based construction group working on the repairs. An excavator on a barge in the river placed the stones, which were brought in by a smaller barge.

The funding for the project came through The Conservation Fund, a Virginia-based nonprofit that helps local projects with climate resiliency work. The organization recently received a grant from Dominion Energy, the utility company that strung a power line across the James River within view of Jamestown Island despite protests from Preservation Virginia and other preservation organizations. In 2017, Dominion handed out $90 million to various organizations in the area working to restore or maintain historic sites as a way of mitigating the impacts of the power lines, as press reported at the time.

Only the beginning

While the newly reinforced wall should protect against future erosion triggered by the increased storm pressure of waves, Jamestown is also coping with a wider range of flooding issues brought on by climate change.

Rising sea levels, for example, threaten coastlines and riversides throughout Virginia — and the higher water table isn’t a factor the sea wall can shield the site against, Gunn says.

And despite how long Jamestown has been recognized as a rich archaeological site, only a tiny percentage of the site has been excavated. Preservation Virginia itself has spent 28 years working on the approximate acre and a half that holds the original early 17th-century British military fort — and the organization oversees more than 22 acres in total. To document the rest of the island properly, water has to be kept away, Givens says.

“What kind of archaeology can you do when you only have five to 10 years to dig before sea levels rise?” Givens asks.

Archaeologists also worry about what the pattern of encroaching and receding waters will damage. Flooding further erodes burial sites already under excavation, and cycling between wet and dry conditions destroys bone, Givens adds.

To keep acres of unexamined land from turning into swamp due to rising ground water levels, Preservation Virginia hopes to elevate buildings, roads, and other portions of the landscape while boosting methods for dewatering the sites. Flood berms and pumping systems might be used. Meanwhile, the organization will track the water table and build 3D models with their ground-penetrating radar to keep tabs on the water ingress’s evolution.

All the coming work will be significantly more expensive than the sea wall protection, though Preservation Virginia doesn’t yet have a firm estimate of the cost. In the end, whatever solutions the organization designs and executes will echo what previous tenants of the island have managed. “People have been adapting to this place for 12,000 years,” says Givens. “It's just there's some urgency to it (now), given what's happening to our planet.”